Untitled: image via Poppy McPherson @ooppymcp, 27 December 2017

Untitled: image via Poppy McPherson @ooppymcp, 27 December 2017

Pod-Hatched Stick-Insect No-Evil-Seeing Death Lady w/ Bright Red-Orange Slime Mold Growth in Her Hair and 1000 x Stronger Than Glinting Steel Heart

Aung San Suu Kyi: no ‘substantive’ talks.: photo by Soe Zeya Tun/Reuters, 27 December 2017

Aung San Suu Kyi avoided discussing reports of Rohingya women and girls being raped by

Myanmar troops and police when she met a senior UN official, according

to an internal memo seen by the Guardian.

Pramila Patten, the special envoy on sexual violence in conflict, travelled to the country for a four-day visit in mid-December to raise the crisis with government officials.

But she said Aung San Suu Kyi, a state counsellor in the Myanmar government, refused to engage in “any substantive discussion” of reports that soldiers, border guard police and Rakhine Buddhist militias carried out “widespread and systematic” sexual violence in northern Rakhine state.

“The meeting with the state counsellor was a cordial courtesy call of

approximately 45 minutes that was, unfortunately, not substantive in nature,” she wrote in a letter sent to UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres last week.

More than 655,000 Rohingya, members of a persecuted and stateless Muslim minority, have fled to Bangladeshi refugee camps since violence began in Myanmar’s northern Rakhine state in August. Médecins Sans Frontières believes at least 6,700 Rohingya were killed during “clearance operations” ostensibly targeting militants, while many survivors say women and girls were gang-raped.

Instead of discussing the claims directly, Patten said Aung San Suu Kyi informed her she would enjoy “a number of good meetings” with senior Myanmar officials.

During these meetings, she was told by representatives of the military and civilian government that reports of atrocities were “exaggerated and fabricated by the international community”.

“Moreover, a belief was expressed that those who fled did so due to an affiliation with terrorist groups, and did so to evade law enforcement,” she wrote.

Myanmar’s army has cleared itself of any wrongdoing in an internal investigation dubbed a “whitewash” by human rights groups.

While in the country, Patten met the man who headed that investigation, Lt-Gen Aye Win, who explained their methodology.

“The military investigation, which consisted of armed men in uniform ‘interrogating’ civilians in large group settings, often on camera, and then presenting rations to communities following their testimony and cooperation, clearly occurred under coercive circumstances, where the incentive structure was not to lodge complaints,” Patten wrote.

“Accordingly, over 800 interviews yielded zero reports of sexual or other violence against civilians by the armed and security forces,” she said.

Patten also expressed concerns about plans to send Rohingya who have fled back to Myanmar, citing the “prevailing climate of impunity” in the country.

Bangladesh and Myanmar have agreed to the “speedy” repatriation of Rohingya, scheduled to start by the end of January.

But many Rohingya say they will not return voluntarily until they are given citizenship as well as guarantees that they will be safe and not put into internment camps. Tens of thousands have been living in such camps elsewhere in Rakhine state since violence in 2012.

Skye Wheeler, the researcher for Human Rights Watch who investigated the sexual violence allegations, said Myanmar was denying a “terrible truth”.

“The lack of acknowledgement or care the Myanmar authorities including Aung San Suu Kyi have shown for Rohingya women and girls who have been brutally raped by Myanmar soldiers as part of their ethnic cleansing campaign is almost as shocking as the horrific crimes themselves,” she told the Guardian.

“It’s like a second attack, to endure a vicious gang rape and then to be ignored, as if you don’t matter at all, to have that terrible truth denied.”

The Myanmar government was contacted for comment.

Kayleigh E. LongVerified account @ayleighk

Pramila Patten, the special envoy on sexual violence in conflict, travelled to the country for a four-day visit in mid-December to raise the crisis with government officials.

But she said Aung San Suu Kyi, a state counsellor in the Myanmar government, refused to engage in “any substantive discussion” of reports that soldiers, border guard police and Rakhine Buddhist militias carried out “widespread and systematic” sexual violence in northern Rakhine state.

“The meeting with the state counsellor was a cordial courtesy call of

approximately 45 minutes that was, unfortunately, not substantive in nature,” she wrote in a letter sent to UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres last week.

More than 655,000 Rohingya, members of a persecuted and stateless Muslim minority, have fled to Bangladeshi refugee camps since violence began in Myanmar’s northern Rakhine state in August. Médecins Sans Frontières believes at least 6,700 Rohingya were killed during “clearance operations” ostensibly targeting militants, while many survivors say women and girls were gang-raped.

Instead of discussing the claims directly, Patten said Aung San Suu Kyi informed her she would enjoy “a number of good meetings” with senior Myanmar officials.

During these meetings, she was told by representatives of the military and civilian government that reports of atrocities were “exaggerated and fabricated by the international community”.

“Moreover, a belief was expressed that those who fled did so due to an affiliation with terrorist groups, and did so to evade law enforcement,” she wrote.

Myanmar’s army has cleared itself of any wrongdoing in an internal investigation dubbed a “whitewash” by human rights groups.

While in the country, Patten met the man who headed that investigation, Lt-Gen Aye Win, who explained their methodology.

“The military investigation, which consisted of armed men in uniform ‘interrogating’ civilians in large group settings, often on camera, and then presenting rations to communities following their testimony and cooperation, clearly occurred under coercive circumstances, where the incentive structure was not to lodge complaints,” Patten wrote.

“Accordingly, over 800 interviews yielded zero reports of sexual or other violence against civilians by the armed and security forces,” she said.

Patten also expressed concerns about plans to send Rohingya who have fled back to Myanmar, citing the “prevailing climate of impunity” in the country.

Bangladesh and Myanmar have agreed to the “speedy” repatriation of Rohingya, scheduled to start by the end of January.

But many Rohingya say they will not return voluntarily until they are given citizenship as well as guarantees that they will be safe and not put into internment camps. Tens of thousands have been living in such camps elsewhere in Rakhine state since violence in 2012.

Skye Wheeler, the researcher for Human Rights Watch who investigated the sexual violence allegations, said Myanmar was denying a “terrible truth”.

“The lack of acknowledgement or care the Myanmar authorities including Aung San Suu Kyi have shown for Rohingya women and girls who have been brutally raped by Myanmar soldiers as part of their ethnic cleansing campaign is almost as shocking as the horrific crimes themselves,” she told the Guardian.

“It’s like a second attack, to endure a vicious gang rape and then to be ignored, as if you don’t matter at all, to have that terrible truth denied.”

The Myanmar government was contacted for comment.

Yet another damning report about Aung San Suu Kyi's mishandling of the #RohingyaCrisis emerges: image via Women in the World @WomenintheWorld, 27 December 2017

Kayleigh E. LongVerified account @ayleighk

State media poem about The Lady today:

Joe Freeman Retweeted Kayleigh E. Long

Joe Freeman added,

Joe Freeman added,

"Frail like a leaf" and "old and frail"

This poem in state media is supposed to be praising Aung San Suu Kyi, right?

image via Joe Freeman @joefree215, 26 December 2017

The term #FakeNews has been thrown around with abandon this year, inc in Myanmar. This picture shows real consequences on attacking a free press. @Reuters journalist Kyaw Soe Oo hugged by his sister on way into court in Myanmar today after two weeks of incommunicado detention: image via Jerome Taylor @Jerome Taylor, 27 December 2017

@Reuters Myanmar journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo appear in court, remanded for another 14 days: image via Reuters Top News @Reuters, 27 December2017

@Reuters Myanmar journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo appear in court, remanded for another 14 days: image via Reuters Top News @Reuters, 27 December2017

“These two journalists are being held for simply doing their jobs and have done nothing wrong. It is time for Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo to be released”: @Reuters spokesperson: tweet via Simon Lewis @Simonddlewis, 27 December 2017

@Reuters journalists @walone4 (blue shirt) and Kyaw Soe Oo after emerging from a van for their brief court hearing in Yangon. They have been held incommunicado by Myanmar authorities for the past 2 weeks. Pics by @ye_aung_thu: image via Sally Mairs @ssmairs, 26 December 2017

@Reuters journalists @walone4 and Kyaw Soe Oo (grey shirt) after emerging from a van for their brief court hearing in Yangon. They have been held incommunicado by Myanmar authorities for the past 2 weeks. Pics by @ye_aung_thu: image via Sally Mairs @ssmairs, 26 December 2017

“I believe that he didn’t commit any crime,” said Pan Ei Mon of her husband. Here's Wa Lone, a hero in a blue racing driver's suit (provided by police), seeing her today for the first time in two weeks. He faces up to 14 years in prison for doing journalism.: image via Simon Lewis @Simondlewis, 27 December 2017

“I believe that he can come home soon," said Kyaw Soe Oo's sister, Nyo Nyo Aye today, after getting her first chance to see him in two weeks. This brave young journalist is accused under a law designed for spies. #FreeWaLoneKyawSoeOo: image via Simon Lewis @Simondlewis, 27 December 2017

Two Reuters journalists are remanded in custody for another fortnight by a Myanmar court, following their first public appearance since being arrested under a secrecy law that carries up to 14 years in jail.: image via AFP news agency @AFP, 26 December 2017

@Reuters journalists @walone4 (blue shirt) and Kyaw Soe Oo after emerging from a van for their brief court hearing in Yangon. They have been held incommunicado by Myanmar authorities for the past 2 weeks. Pics by @ye_aung_thu: image via Sally Mairs @ssmairs, 26 December 2017

@Reuters journalists @walone4 and Kyaw Soe Oo (grey shirt) after emerging from a van for their brief court hearing in Yangon. They have been held incommunicado by Myanmar authorities for the past 2 weeks. Pics by @ye_aung_thu: image via Sally Mairs @ssmairs, 26 December 2017

“I believe that he didn’t commit any crime,” said Pan Ei Mon of her husband. Here's Wa Lone, a hero in a blue racing driver's suit (provided by police), seeing her today for the first time in two weeks. He faces up to 14 years in prison for doing journalism.: image via Simon Lewis @Simondlewis, 27 December 2017

“I believe that he can come home soon," said Kyaw Soe Oo's sister, Nyo Nyo Aye today, after getting her first chance to see him in two weeks. This brave young journalist is accused under a law designed for spies. #FreeWaLoneKyawSoeOo: image via Simon Lewis @Simondlewis, 27 December 2017

Two Reuters journalists are remanded in custody for another fortnight by a Myanmar court, following their first public appearance since being arrested under a secrecy law that carries up to 14 years in jail.: image via AFP news agency @AFP, 26 December 2017

“We will face it the best we can because we have never done anything wrong. We have never violated the media law nor ethics. We will continue to do our best”: @walone4: tweet via Simon Lewis @Simonddlewis, 27 December 2017

Can't even describe my joy at being able to see Wa Lone and hold his hand. We talked for a few minutes.

He's well and his spirits are high.

He is unbroken.

He is unbreakable. #FreeWaLoneKyawSoeOo: image via Antoni Slodkowski @slodek, 26 December 2017

My Reuters colleague Wa Lone serenely negotiates the scrum of reporters - many of them his friends - waiting outside a Myanmar court today. #FreeWaLoneKyawSoeOo: image via Andrew RC Marshall @Journotopia, 26 December 2017

Two Reuters journalists are remanded in custody for another fortnight by a Myanmar court, following their first public appearance since being arrested under a secrecy law that carries up to 14 years in jail.: image via AFP news agency @AFP, 26 December 2017

Two Reuters journalists are remanded in custody for another fortnight by a Myanmar court, following their first public appearance since being arrested under a secrecy law that carries up to 14 years in jail.: image via AFP news agency @AFP, 26 December 2017

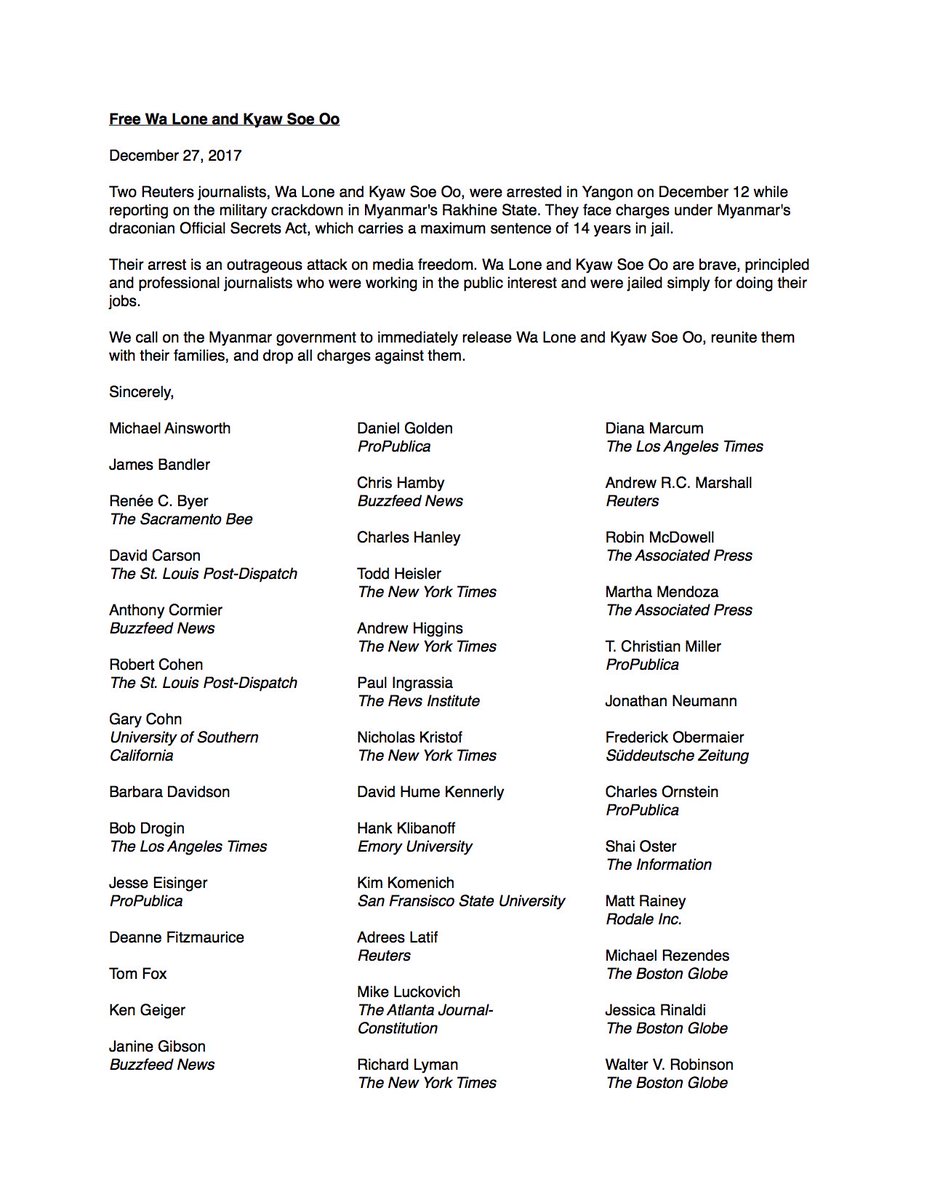

Statement this morning signed by 50 Pulitzer Prize winning journalists calling for the release of @Reuters journalists Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone who are detained in Myanmar.: image via Timothy McLaughlin @TMclaughlin3, 27 December 2017

So was the Buddha just Fake News sold to the world by lying monks, or actually an unwonted excrescence of slime mold growth from another galaxy?

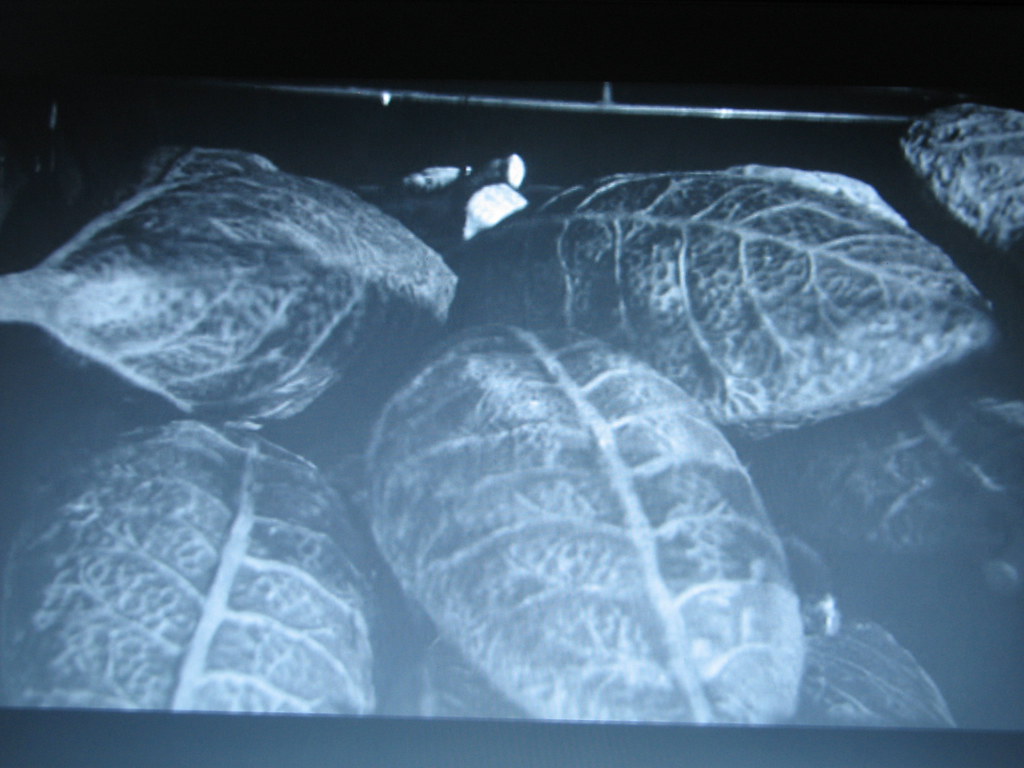

CT Scan of 1 000-Year-Old Buddha Statue Reveals Mummified Monk Hidden Inside: image via History Lovers Club @historylvrsclub, 19 December 2017

Pods | These strange pads float along in the Italian Gardens at Biltmore, and they always remind me of the pods from Invasion of the Body Snatchers for some reason. [Biltmore, Asheville, NC]: photo by Mike McBride, 22 September 2013

10.26.11 - "Invasion of the Body Snatchers" | Our Pick for Wednesday, October 26th, 2011: photo by Movies in LA, 24 October 2011

Invasion of the Body Snatchers | At the Hollywood Forever Cemetery outdoor screening: photo by vmiramontes, 19 June 2010

Slime Mold Growth in the Garden of Mindfulness (Invasion of the Body Snatchers)

the pods [Invasion of the Body Snatchers]: photo by Tnarik Innael, 1 July 2007

"They are here" [Invasion of the Body Snatchers]: photo by Tnarik Innael, 1 July 2007

Invasion of the body snatchers or Burke and Hare come south? | Walking outside the York NHS walk-in (health) centre... Too late for some? [a serious note: Possibly two of Scotland's most gruesome imports were the serial killers William Burke and William Hare. Burke and Hare hailed from Ulster and moved to Scotland to work as labourers on the Union Canal. Ever aware of a market to meet, Burke and Hare set themselves up as procurers of human bodies to satisfy the demand of Edinburgh's medical schools. Originally the two would dig up the graves of the recently departed in the dead of night, steal the body and then sell it for cash to a doctor for use during anatomy demonstrations. Sounds like hard work and Burke and Hare must have thought so, too, because they decided there was no need to go digging. The two entrepreneurs started murdering people in Edinburgh's old town and selling the cadavers of the victims to the medical schools on an 'ask no questions basis.' The murder of their 16th victim led to their arrest, along with Burke's mistress and Hare's wife, yet the courts had little evidence with which to conduct a successful prosecution. The Lord Advocate, Sir William Rae, offered Hare immunity from prosecution if he would turn King's evidence. The evidence Hare and his wife provided sent Burke to his death on the gallows on 28 January, 1829 while his mistress Helen MacDougall escaped when the charges against her were found not proven.]: photo by Xenones, 28 November 2005

Invasion of the Body Snatchers: photo by AJ, 25 June 2006

Weird algae bloom | Invasion of the Body Snatchers [Acadia, ME]: photo by Nadya Peek, 27 May 2011

Invasion of the body snatchers [Dexter, MI] : photo by ellenm1, 15 October 2010

Red slime mold: Tubifera sp. | On a rotting log, open 2nd-growth deciduous woods. Big one is 1.7 cm across. Wasn't even sure what kingdom this stuff was! [New Brunswick, NJ]: photo by Anita Gould, 10 June 2012

UPDATE: @Reuters statement on current situation with detained journalists in Myanmar - #FreeWaLoneKyawSoeOo #MyanmarPressFreedom: image via Katherine Finnerty @KPFinnerty, 27 December 2017

strange... | Physarum rubiginosum [orange slime mould]: photo by Scott Darbey, 23 June 2012

021112. As everything else loses its vibrant colours, this stuff just stands out even more. [orange slime mould]: photo by Simon Evans, 2 November 2012

021112. As everything else loses its vibrant colours, this stuff just stands out even more. [orange slime mould]: photo by Simon Evans, 2 November 2012

021112. As everything else loses its vibrant colours, this stuff just stands out even more. [orange slime mould]: photo by Simon Evans, 2 November 2012

old vomit face [fuligo septica, firenze]: photo by Crispin Semmens, 2 December 2012

Slime Mold: Early and Later | I don't know the true name of this interesting growth that appeared atop one of our mulch piles the other day after a lot of rain. Just a few hours later, and after some warm sun (right), it had quite a different appearance. Good luck understanding these! One thing I've learned is that slime molds are NOT fungi. They belong to the Protista kingdom. Probably Fuligo septica. [NC]: photo by Melinda Young Stuart, 13 July 2012

Bryozoan | The first thing Shari said was "Invasion of the Body Snatchers". Just when you were feeling safe. Stansberry Lake, Washington [Pectinateella magniica]: photo by David Seibold, 27 September 2017

Bryozoan | The first thing Shari said was "Invasion of the Body Snatchers". Just when you were feeling safe. Stansberry Lake, Washington [Pectinateella magniica]: photo by David Seibold, 27 September 2017

Bryozoan | The first thing Shari said was "Invasion of the Body Snatchers". Just when you were feeling safe. Stansberry Lake, Washington [Pectinateella magniica]: photo by David Seibold, 27 September 2017

Invasion of the Body Snatchers | From

the 1956 version of "Invasion of the Body Snatchers", Miles and Becky

attempt to hide out in this cave. The cave is located in the Bronson

Canyon area of the Hollywood Hills. This is the same cave opening that

is seen as the Bat Cave from the '60s TV series.: photo by Tony Hoffarth, 18 September 2009

frantic [Invasion of the Body Snatchers]: photo by Tnarik Innael, 1 July 2007

memories of lost lives, kept in a bit of cheap plastic

In this Dec. 23, 2017 photo, Mujibullah, 22, a Rohingya refugee watches a video, which he has shot in Myanmar before crossing over into Bangladesh, at Kutupalong refugee camp in Ukhiya, Bangladesh. This video shows people in the Myanmar village of Borgiyabil frantically trying to extinguish the flames after soldiers lit their homes on fire with Molotov cocktails. For many Rohingya living in refugee camps in Bangladesh, all that remains of their old lives in Myanmar are memories captured in photos and videos on their cellphones. Since August, more than 630,000 Rohingya Muslims have fled to Bangladesh to escape attacks by Myanmar security forces. Few refugees had the chance to grab many belongings when they fled, but most took their cellphones.: photo by A.M. Ahad/AP, 23 December 2017

KUTUPALONG, Bangladesh (AP) — Abdul Hasan can spend hours watching old videos he shot on his cellphone.

“My heart aches for my village, my home,” the 16-year-old Rohingya

refugee from Myanmar said in a camp in neighboring Bangladesh. “That’s

why we have brought these memories, this video, from Myanmar.”

Since late August, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims have

fled to Bangladesh to escape attacks by Myanmar security forces. But

before fleeing from advancing soldiers, few Rohingya had time to grab

many of their belongings. Instead, they poured across the border into

Bangladesh bringing with them little more than horror stories of

marauding forces and memories of terrifying treks through the forests.

Their old lives — homes, cattle, villages, everything — are gone. All they have left is their memories.

A Rohingya refugee at Kutupalong refugee camp in Ukhiya, Bangladesh shares images stored on his cellphone.: image from a video by Rishabh Jain, 23 December 2017

But if they’re lucky, some of those memories are stored on the cellphones many refugees managed to bring with them.

It’s the closest Hasan gets to experiencing his old life and country.

One video shows him having what he calls a “coconut party.” A song

hailing the bravery of a Rohingya rebel leader plays in the background

as Hasan and his friends eat coconuts, and laugh as they throw them at

each other.

“When I watch this video, I think of my country, Myanmar. It really breaks my heart so much,” he said.

The government of Buddhist-majority Myanmar has refused to accept

Rohingya as a minority group, even though some have lived in the country

for generations. Rohingya were stripped of their citizenship in 1982,

denying them almost all rights and rendering them stateless.

In late August, attacks by Rohingya militants triggered a brutal and

indiscriminate response by Myanmar’s military, sending more than 630,000

Rohingya fleeing to nearby Bangladesh.

Mohammad Fahid, 15, said he often finds himself looking through old

photos and videos on his phone. He misses his friends. He misses school.

“I shared a lot of good times and laughter with my friends. I can’t

do that here anymore,” he said. “We could go to school, now we can’t. So

that is why I have kept these pictures. To remember.”

There is little work for the adults in the camps, and almost no

schools for the children, who make up nearly 60 percent of the refugees.

There is plenty of time to scroll through cellphones.

But not all the phone memories are happy.

Mujib Ullah is sitting with his sisters in their new home, a dark

one-room shelter made from bamboo and plastic sheets. Ullah, 22, is

showing a video of people in the Myanmar village of Borgiyabil

frantically trying to extinguish the flames after soldiers lit their

homes on fire with Molotov cocktails. The villagers used buckets of sand

and water to try to put out the fires, but the homes kept burning,

Ullah said.

A few hours after shooting his video, Ullah returned to his own

village nearby and found his neighbors coming out of their homes.

Everyone thought the soldiers had left. Suddenly gunfire rang out.

Soldiers they hadn’t spotted were firing into the crowd.

“Some people were able to save themselves, others could not,” Ullah

said. “My brother could not save himself. He was riddled with bullets.”

In this Dec. 23, 2017 photo, Mujibullah, 22, a Rohingya refugee watches a video, which he has shot in Myanmar before crossing over into Bangladesh, at Kutupalong refugee camp in Ukhiya, Bangladesh. : photo by A.M. Ahad/AP, 23 December 2017

In this Dec. 23, 2017 photo, an unidentified Rohingya refugee watches a video, which he has shot in Myanmar before crossing over into Bangladesh, at Kutupalong refugee camp in Ukhiya, Bangladesh.: photo by A.M. Ahad/AP, 23 December 2017

In this Dec. 23, 2017 photo, Mujibullah, 22, a Rohingya refugee watches a video, which he has shot in Myanmar before crossing over into Bangladesh, at Kutupalong refugee camp in Ukhiya, Bangladesh.their cellphones.: photo by A.M. Ahad/AP, 23 December 2017

beyond bagdad (backing into what past)

Late grandmother's room, Sarajevo. Sunday. Family time.: image via Damir Sagolj, 24 December 2017

Against: image via Damir Sagolj, 20 December 2017

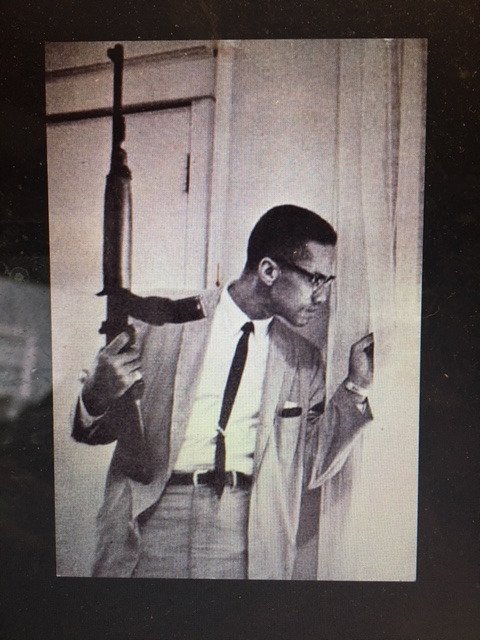

Don Hogan Charles, the first black staff photographer to be hired by the NYTimes, has died. He shot amazing photos: this iconic image of Malcolm X for Ebony magazine, beautiful photos of Harlem, where he lived, and so many more. RIP: image via Rachel Swarns @rachelswarns, 24 December 2017

Marilyn approaches | Marilyn Monroe on the set of Niagara, 1953: photo by Michael Ryerson, 17 December 2017

Los Ranchos de Albuquerque, New Mexico: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, December 2017

Bagdad, California: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, November 2017

Bagdad, California: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, November 2017

Bagdad, California: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, November 2017

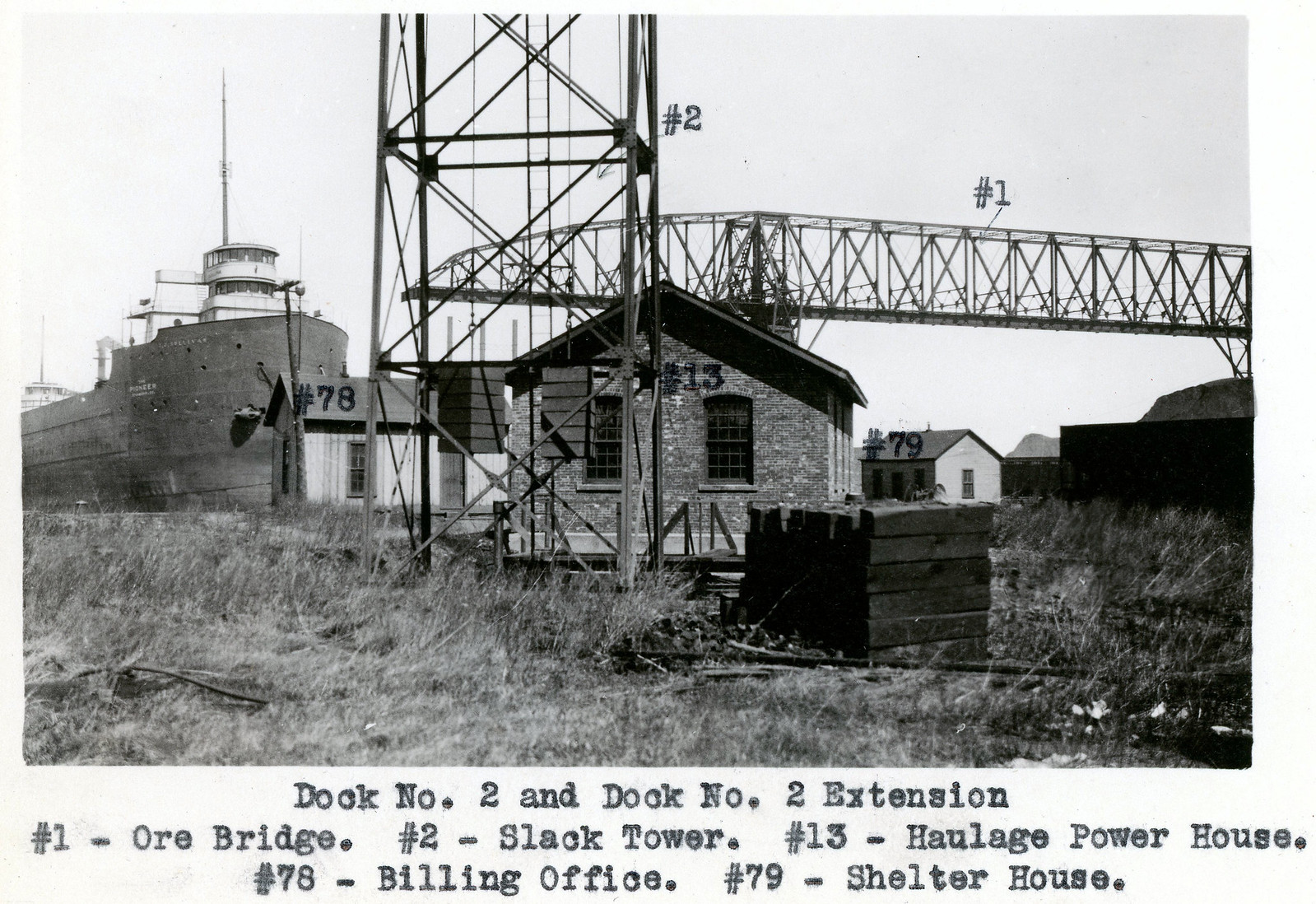

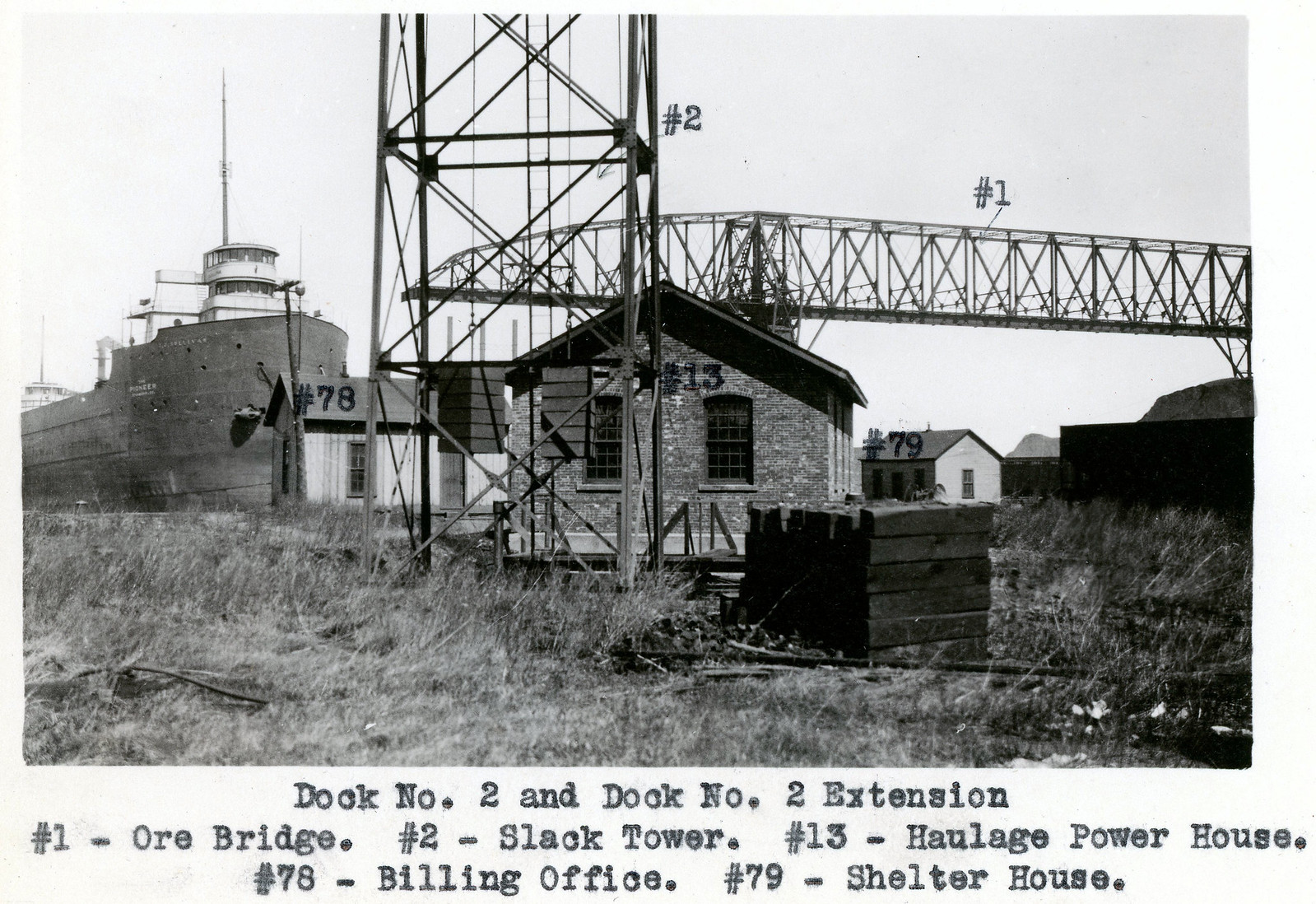

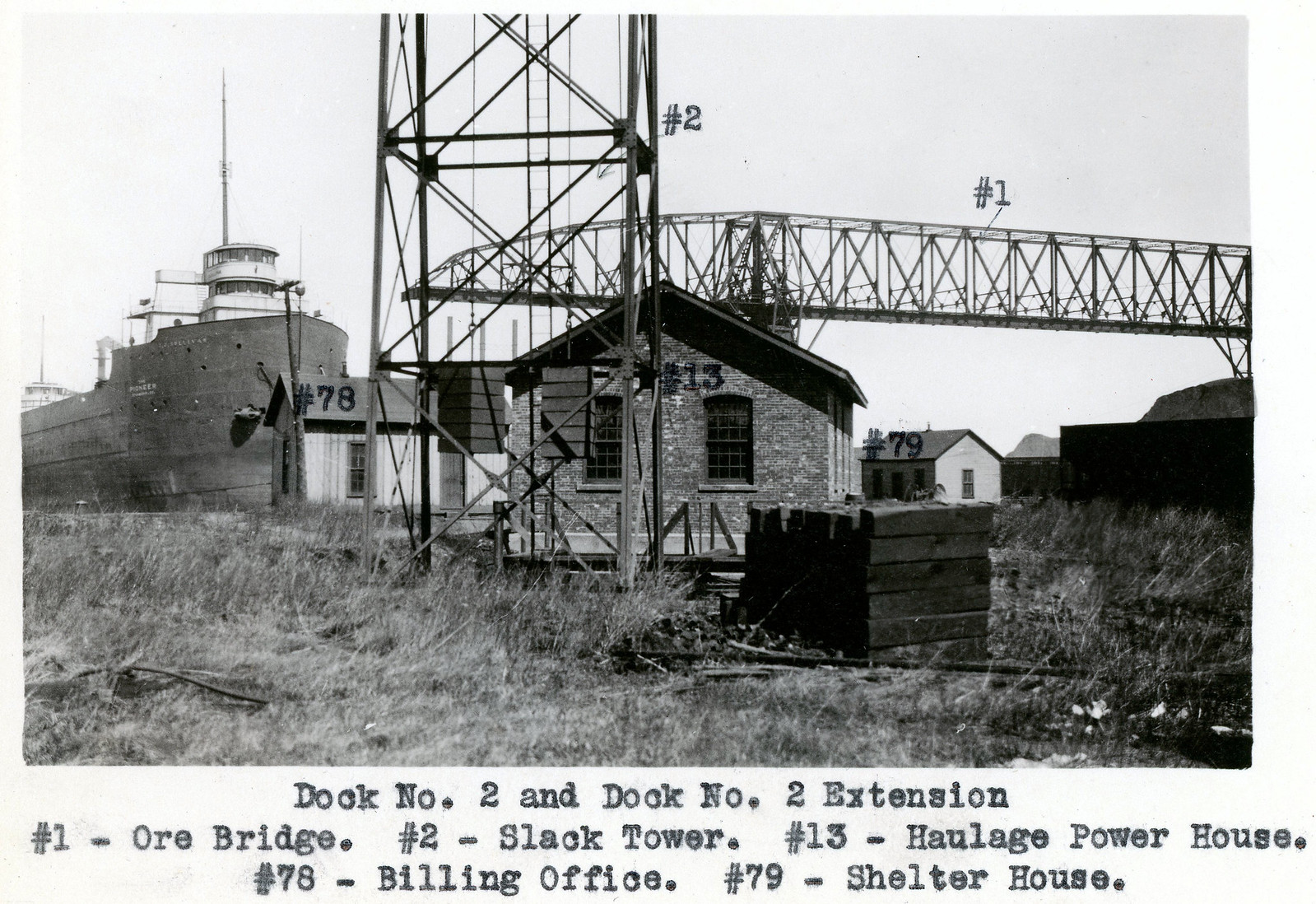

NYCRR Dock No. 2 and Dock #2 Extension Ore Bridge. From: The New York Central Railroad | Properties at Ashtabula, Ohio | 1924 |Ore Boat: J.J. Sullivan 1907-1976 (1987) | Steel Great Lakes bulk freighter | Built at Cleveland OH by American Ship Building Co., Hull 439 Launched Sept 14, 1907 |552’ LOA, 532’ LBP, 56’ beam, 31’ depth |1 deck, arch cargo hold construction, hatches @ 12’, coal-fired boilers, triple expansion engine, 1760 IHP| Enrolled at Cleveland OH Oct 10, 1907 (#18) | 532.0 x 56.0 x 31.0, 7077 GT, 5541 NT US 204624 to: Superior Steamship Co., Cleveland OH, Hutchinson & Co., Mgr. (home port Fairport OH) | Entered service 1907 | Transferred 1914 to Pioneer Steamship Co. | Home port to Wilmington DE 1932 | Rebuilt and repowered 1950 with Skinner unaflow engine |Remeasured to 539.8 x 56.0 x 27.5, 7176 GT, 5730 NT | Sold 1963 to Inland Steel Co., Chicago IL and renamed Clarence B. Randall (2) | Sold for scrap 1976 to Luria Brothers Inc. and laid up at Milwaukee WI. Resold 1980 to North Central Marine for grain storage (used only briefly for this purpose). Was scheduled 1981 for conversion to barge but conversion never occurred (and was to have been renamed Wannamingo but renaming never occurred). Sold for scrap 1987 to M & M Steel Inc., Windsor ON, towed to Windsor and scrapped there. - Vessel Histories of Sterling Berry: photo by Ashtabula Archive, 22 December 2017

NYCRR Dock No. 2 and Dock #2 Extension Ore Bridge. From: The New York Central Railroad | Properties at Ashtabula, Ohio | 1924 |Ore Boat: J.J. Sullivan 1907-1976 (1987) | Steel Great Lakes bulk freighter | Built at Cleveland OH by American Ship Building Co., Hull 439 Launched Sept 14, 1907 |552’ LOA, 532’ LBP, 56’ beam, 31’ depth |1 deck, arch cargo hold construction, hatches @ 12’, coal-fired boilers, triple expansion engine, 1760 IHP| Enrolled at Cleveland OH Oct 10, 1907 (#18) | 532.0 x 56.0 x 31.0, 7077 GT, 5541 NT US 204624 to: Superior Steamship Co., Cleveland OH, Hutchinson & Co., Mgr. (home port Fairport OH) | Entered service 1907 | Transferred 1914 to Pioneer Steamship Co. | Home port to Wilmington DE 1932 | Rebuilt and repowered 1950 with Skinner unaflow engine |Remeasured to 539.8 x 56.0 x 27.5, 7176 GT, 5730 NT | Sold 1963 to Inland Steel Co., Chicago IL and renamed Clarence B. Randall (2) | Sold for scrap 1976 to Luria Brothers Inc. and laid up at Milwaukee WI. Resold 1980 to North Central Marine for grain storage (used only briefly for this purpose). Was scheduled 1981 for conversion to barge but conversion never occurred (and was to have been renamed Wannamingo but renaming never occurred). Sold for scrap 1987 to M & M Steel Inc., Windsor ON, towed to Windsor and scrapped there. - Vessel Histories of Sterling Berry: photo by Ashtabula Archive, 22 December 2017

NYCRR Dock No. 2 and Dock #2 Extension Ore Bridge. From: The New York Central Railroad | Properties at Ashtabula, Ohio | 1924 |Ore Boat: J.J. Sullivan 1907-1976 (1987) | Steel Great Lakes bulk freighter | Built at Cleveland OH by American Ship Building Co., Hull 439 Launched Sept 14, 1907 |552’ LOA, 532’ LBP, 56’ beam, 31’ depth |1 deck, arch cargo hold construction, hatches @ 12’, coal-fired boilers, triple expansion engine, 1760 IHP| Enrolled at Cleveland OH Oct 10, 1907 (#18) | 532.0 x 56.0 x 31.0, 7077 GT, 5541 NT US 204624 to: Superior Steamship Co., Cleveland OH, Hutchinson & Co., Mgr. (home port Fairport OH) | Entered service 1907 | Transferred 1914 to Pioneer Steamship Co. | Home port to Wilmington DE 1932 | Rebuilt and repowered 1950 with Skinner unaflow engine |Remeasured to 539.8 x 56.0 x 27.5, 7176 GT, 5730 NT | Sold 1963 to Inland Steel Co., Chicago IL and renamed Clarence B. Randall (2) | Sold for scrap 1976 to Luria Brothers Inc. and laid up at Milwaukee WI. Resold 1980 to North Central Marine for grain storage (used only briefly for this purpose). Was scheduled 1981 for conversion to barge but conversion never occurred (and was to have been renamed Wannamingo but renaming never occurred). Sold for scrap 1987 to M & M Steel Inc., Windsor ON, towed to Windsor and scrapped there. - Vessel Histories of Sterling Berry: photo by Ashtabula Archive, 22 December 2017

Louisville [posing clinic, bodybuilding physique contest, Louisville, KY]Berry: photo by Ashtabula Archive, 23 April 2017

Christmas Party given by The Baroness on 12.16.17, East Village, New York City: photo by M. Chaussettes, 21 December 2017

Christmas Party given by The Baroness on 12.16.17, East Village, New York City: photo by M. Chaussettes, 21 December 2017

3 comments:

... ah, this must be them now...

... and a bit of the backstory...

The Branson Canyon cave is also one of the principal locations for the 1953 science-fiction Ultrabad classic, Robot Monster.

The film shows that planet Earth can be conquered by a race of beings who rely on use of small Philco CRT televisions and cheap folding card tables -- which makes events in America over the past eleven-plus months somewhat more comprehensible.

Only goes to show, if you\re patient enough, the key to Everything will always find a way into your watch pocket.

BTW I do love the (well, your) concept of Charlton Ben Heston working up to ramming speed, was reminded of another xmas classic, By Dawn's early Light, in which James Earl Jones receives a no filter cigarette from a congenial female colleague of lower station but never has time to smoke it because he's busy getting the plane up to ramming speed, so as to eliminate Rip Torn from the nuclear exploding universe. And none too soon!

Post a Comment