A los invisibles: photo by museo de arte un, 25 August 2008

mesa 00862: photo by m.r. nelson, 28 January 2018

mesa 00862: photo by m.r. nelson, 28 January 2018

mesa 00862: photo by m.r. nelson, 28 January 2018

Untitled [Inyo, California]: photo by Patrick, October 2017

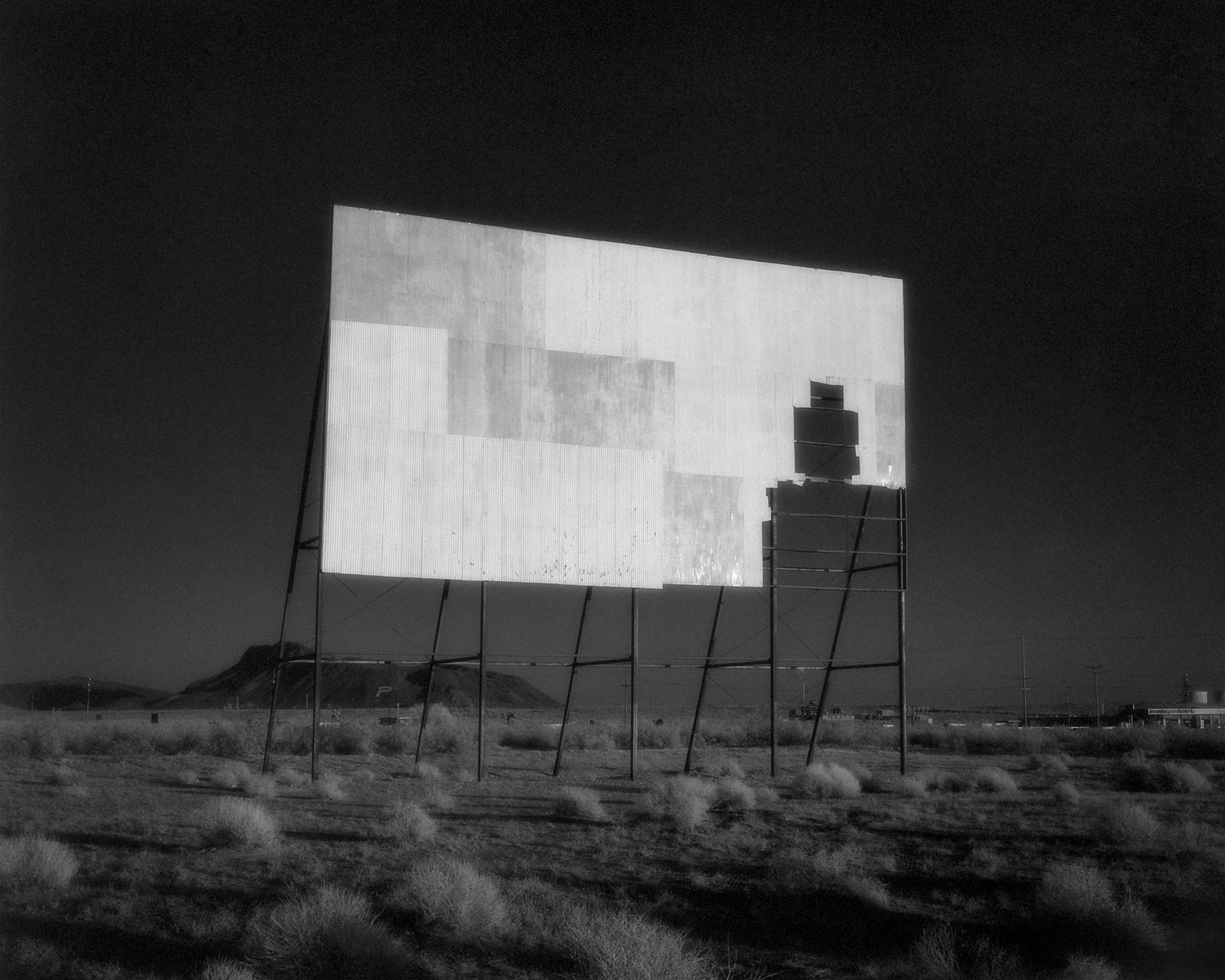

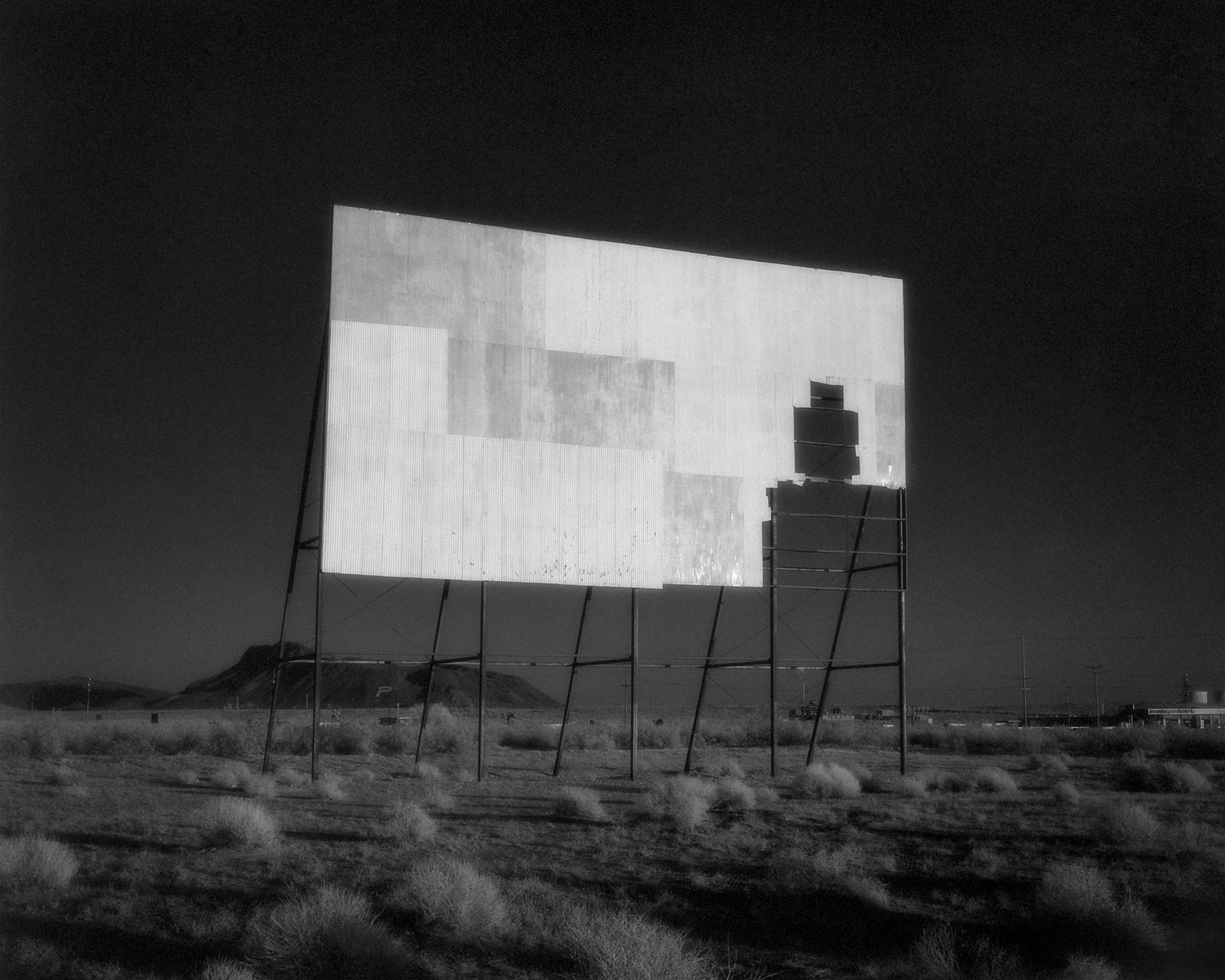

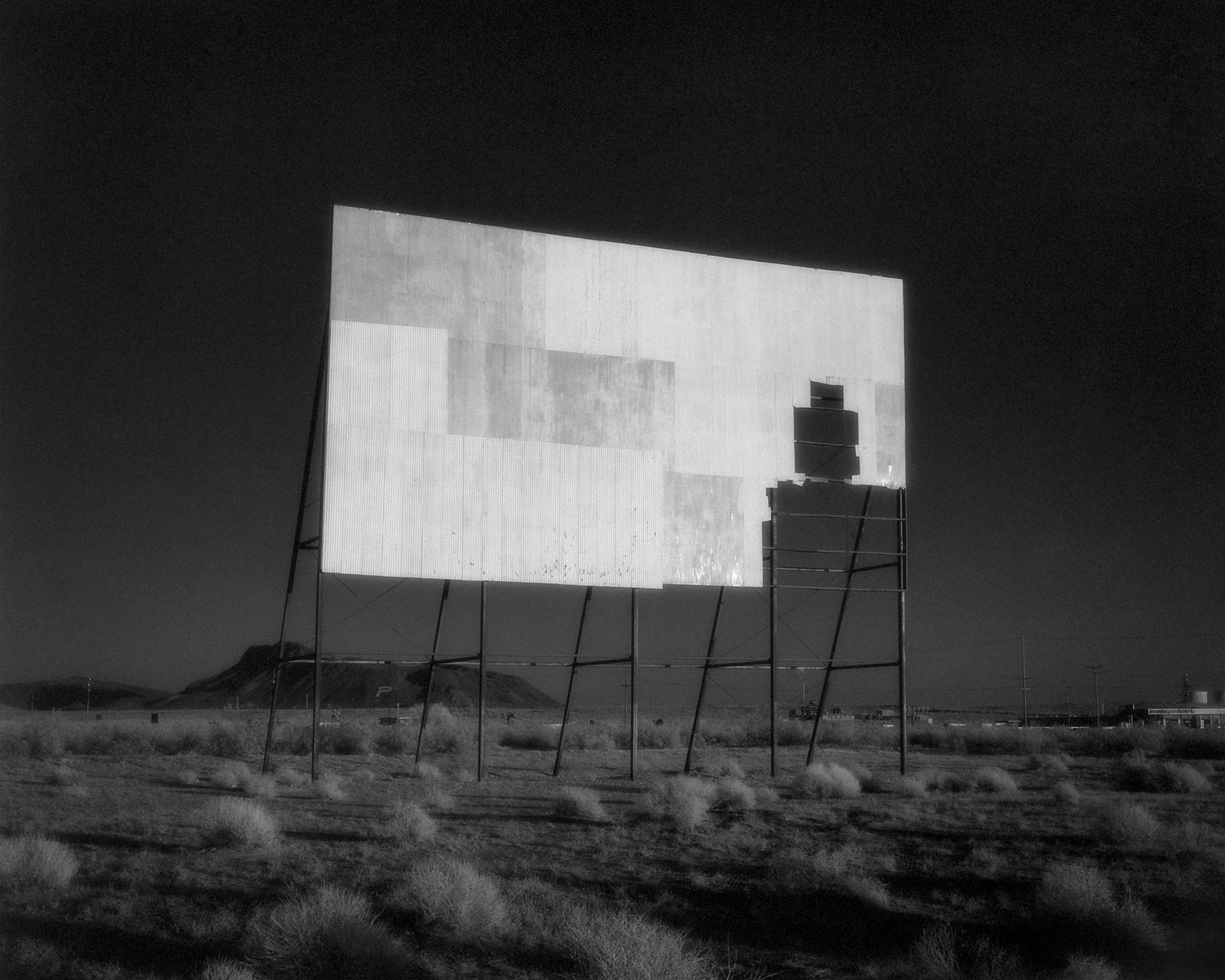

Rio Rancho, New Mexico: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, 21 February 2018

Rio Rancho, New Mexico: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, 21 February 2018

Rio Rancho, New Mexico: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, 21 February 2018

mesa 00869: photo by m.r. nelson, 28 January 2018

mesa 00869: photo by m.r. nelson, 28 January 2018

mesa 00869: photo by m.r. nelson, 28 January 2018

2018-38 | Berkeley, CA: photo by biosfear, February 2018

double feature. parker, az. 2018. | late afternoon at an abandoned desert drive-in theater: photo by eyetwist, 11 February 2018

double feature. parker, az. 2018. | late afternoon at an abandoned desert drive-in theater: photo by eyetwist, 11 February 2018

double feature. parker, az. 2018. | late afternoon at an abandoned desert drive-in theater: photo by eyetwist, 11 February 2018

Seaside, Oregon: photo by Austin Granger, 22 February 2018

Seaside, Oregon: photo by Austin Granger, 22 February 2018

mesa 00857: photo by m.r. nelson, 28 January 2018

mesa 00857: photo by m.r. nelson, 28 January 2018

mesa 00857: photo by m.r. nelson, 28 January 2018

2018-21 | Big Sur, CA: photo by biosfear, 1 January 2018

Seaside, Oregon: photo by Austin Granger, 22 February 2018

Seaside, Oregon: photo by Austin Granger, 22 February 2018

Seaside, Oregon: photo by Austin Granger, 22 February 2018

mesa 00857: photo by m.r. nelson, 28 January 2018

mesa 00857: photo by m.r. nelson, 28 January 2018

mesa 00857: photo by m.r. nelson, 28 January 2018

2018-21 | Big Sur, CA: photo by biosfear, 1 January 2018

Albuquerque, New Mexico: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, 23 February 2018

Albuquerque, New Mexico: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, 23 February 2018

Albuquerque, New Mexico: photo by Jorge Guadalupe Lizárraga, 23 February 2018

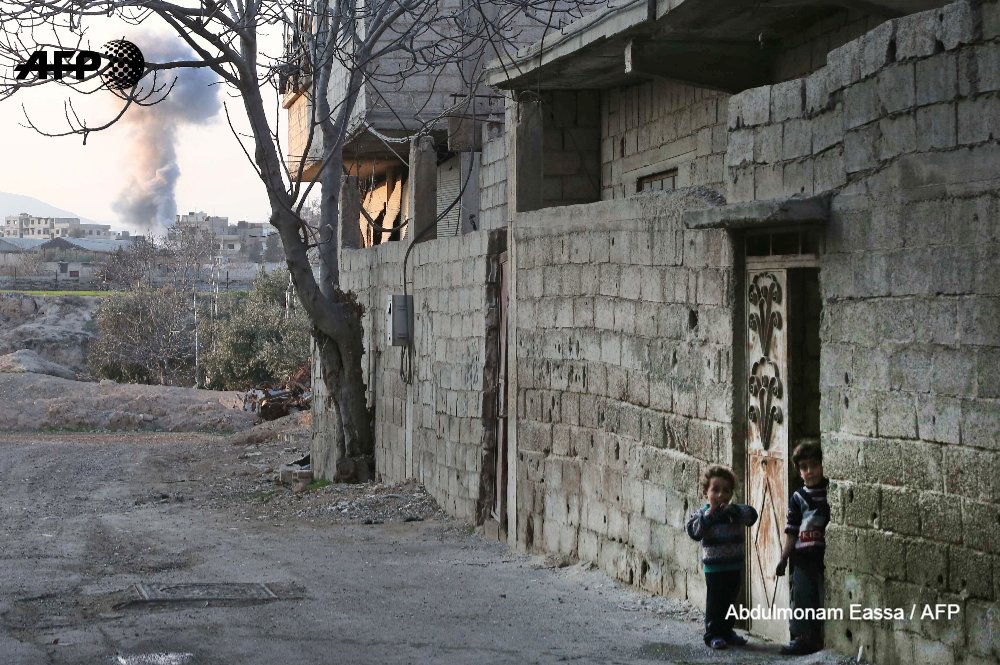

This image by our photographer @AmmarSulaiman91 shows the extent of the ruin in Eastern #Ghouta, and its proximity to Damascus. Like hundreds were being bombed daily with impunity in Richmond, or the Bronx.: image via Patrick Galey @patrickgaley, 24 February 2018

#BREAKING: New regime strikes in Syria enclave despite ceasefire call: monitor - via @afp: tweet via Maya Gebeily @GebeilyM, 24 February 2018

All

eyes on Syria’s ceasefire this morning. White Helmets rescue teams in

Eastern Ghouta continue to report air strikes and shelling, including

the use of what appear to be incendiary munitions in Douma.: tweet via Louisa Loveluck, @leloveluck, 25 February 2018

#BREAKING 24-2-2018

Assad's army and his allies start a ground military incursion [into]

#EasternGhouta from the east and doesn't respect the international laws

and the decision to desolation ... now 3 warplanes on ghouta sky are

launching air strikes on #EasternGhouta: image via Amer almohibany @amer_almohibany, 24 February 2018

This morning brought a fresh wave of attacks against #EasternGhouta: Artillery shelling by the Syrian military on targeting Hazza, Kafr Batna, Jisrin, Ein Tarma, Douma, and Harasta. Pro-government forces launched a ground attack in al-Marj area in an attempt to gain territory. 12:25 AM - 25 Feb 2018: tweet via Siege Watch @SiegeWatch, 25 February 2018

This morning brought a fresh wave of attacks against #EasternGhouta: Artillery shelling by the Syrian military on targeting Hazza, Kafr Batna, Jisrin, Ein Tarma, Douma, and Harasta. Pro-government forces launched a ground attack in al-Marj area in an attempt to gain territory. 12:25 AM - 25 Feb 2018: tweet via Siege Watch @SiegeWatch, 25 February 2018

Death shapes A picture taken [today] shows a Russian-made Syrian army attack helicopter dropping a payload over the rebel-held town of Arbin, in the besieged Eastern Ghouta region on the outskirts of the capital Damascus. / @AFP / #amer_almohibany: image via Amer almohibany @amer_almohibany, 24 February 2018

Death shapes A picture taken [today] shows a Russian-made Syrian army aircraft attacking the rebel-held town of Arbin, in the besieged Eastern Ghouta region on the outskirts of the capital Damascus. / @AFP / #amer_almohibany: image via Amer almohibany @amer_almohibany, 24 February 2018

Death shapes A picture taken [today] shows a Russian-made Syrian army attack helicopter dropping a payload over the rebel-held town of Arbin, in the besieged Eastern Ghouta region on the outskirts of the capital Damascus. / @AFP / #amer_almohibany: image via Amer almohibany @amer_almohibany, 24 February 2018

Death shapes A picture taken [today] shows a Russian-made Syrian army attack aircraft firing a missileover the rebel-held town of Arbin, in the besieged Eastern Ghouta region on the outskirts of the capital Damascus. / @AFP / #amer_almohibany: image via Amer almohibany @amer_almohibany, 24 February 2018

Understanding Eastern Ghouta in Syria: Aron Lund, IRIN News, 23 February 2018

Understanding Eastern Ghouta in Syria

New backgrounder for @IRINnews: what is the Ghouta, why does it matter,

how many civilians are stuck in the enclave, why can't they leave, how

does the siege work, who are the rebels, and what does the government

want?: image via Aron Lund @aronlund, 23 February 2018

The UN says nearly 400,000 civilians are trapped the Eastern Ghouta

suburbs of Damascus, the latest battleground in a series of bloody rebel

defeats in Syria’s cities. Syrian

President Bashar al-Assad’s forces and his Russian allies seem poised for a major ground offensive on the besieged insurgent enclave. What do we know?

Ghouta is an agricultural region ringing Damascus, part of which has succumbed to urban expansion and slum housing in recent decades. In Eastern Ghouta, anti-Assad insurgents have been besieged by the Syrian army since spring 2013.

Recent UN estimates put the enclave’s population at around 393,000, with the UN’s top official in Syria, Ali al-Zatari, saying 272,500 inhabitants are in need of humanitarian assistance. About a third of Eastern Ghouta’s population is internally displaced, including people who have fled from Damascus.

These figures remain uncertain, and previous UN population estimates for besieged areas in Syria have at times proven too high, notably in eastern Aleppo. But although Syrian loyalist or opposition sources may provide lower or higher numbers, the UN records remain the only widely-recognised figures available.

The area is important to the Syrian government, since it encompasses the eastern suburbs of the capital. Large, well-defended, and within mortar range of central Damascus, where the Old City and other neighbourhoods have suffered from rebel shelling, Eastern Ghouta has been a severe irritant to the loyalist camp for years.

Leaving the enclave has long been impossible for most inhabitants, though there are exceptions. A small number of inhabitants, including public employees, are reportedly allowed to come and go through an agreed and mutually supervised checkpoint at Wafideen, near Douma, though it is a risky passage due to land mines, sniper fire, and the aggressive and unpredictable behaviour of both government and rebel forces.

Syrian authorities recently dropped fliers over Eastern Ghouta telling civilians to leave the area, but they have in the past refused entry for people trying to get out.

For example, the UN has tried for eight months to evacuate 500 severely ill or wounded civilians from Eastern Ghouta, including small children. The government refuses to let them out of the enclave, leading to the reported death of 22 of these patients so far.

A smaller group of around 35 patients was allowed out in December, albeit as part of a negotiated swap with detainees released by the rebels, rather than out of respect for humanitarian law. Both sides have made a habit of using prisoners of war and civilian hostages as negotiating chips.

Critics of al-Assad who are thinking of leaving are also fearful of being apprehended by his police forces, which have a decades-long history of arbitrary arrests, detainee abuse, and unlawful executions. Many of those who are apolitical or willing to take their chances with the regime remain concerned that they or their male relatives could be drafted into the army.

The rebels also restrict civilian movement. Amnesty International has noted that the Islam Army, which controls the opposition side of the Wafideen checkpoint, only allows select civilians to leave and has on occasion arrested people for simply asking permission to go.

According to REACH, a UN-backed initiative working on humanitarian reporting, the opposition groups have reportedly banned women, children, and men of fighting age from leaving the enclave, thereby preventing families from exiting together even if some members have been given free passage.

Humanitarian conditions inside Eastern Ghouta are extremely poor. Government shelling, infighting, and misrule by armed opposition groups play a part in that, but the most important reason is a blockade on food and humanitarian assistance imposed by the Syrian army.

How harshly the blockade is enforced has varied over the years. UN and Syrian Arab Red Crescent aid convoys are sometimes allowed in to prevent outright starvation, but permissions are rare and irregular. Aid officials say they are not permitted to deliver anywhere near the amount of food needed, and medical supplies are often stolen or sent back at government checkpoints.

By withholding humanitarian aid, the government has pushed up food prices and inflated the profit margins of a regime-connected businessman granted monopoly rights to trade via the Wafideen crossing, possibly in return for sharing the profits with the president’s entourage. Some rebel groups have been in on the deal: both regime figures and insurgent commanders have made money by taxing food at the expense of local civilians.

From 2014 until 2017, rebel-controlled smuggling tunnels brought in goods not permitted through Wafideen—including weapons and ammunition, but also food, medicine and fuel, which is needed to power electrical generators, water pumps and other basic infrastructure. In spring 2017, the Syrian army captured the tunnels. Since then, accumulating economic and infrastructural problems have diminished the area’s ability to cope with deprivation.

Despite promises of improved humanitarian access as the main rebel groups signed Russian-brokered de-escalation deals last summer, the Syrian military began tightening the screws in late 2017.

In September, the government shut down even the for-profit food trade it had previously allowed through Wafideen. Since then, all but a handful of UN-organised aid convoys have been stopped by the authorities, thus engineering a severe civilian health crisis .

Recent WFP reporting indicates that prices in the enclave have grown by 140 percent since the Wafideen closure and are now six times higher than the national average. According to REACH, a bag of flat bread, which is a staple food in Syria, now costs 94 Syrian pounds in Damascus but 1,500 Syrian pounds in Eastern Ghouta.

Even before the effects of the current crisis were fully felt, humanitarian officials described Eastern Ghouta’s malnutrition levels as the worst ever recorded during the Syrian war. A November 2017 UN survey found that 11.9 percent of children under five were acutely malnourished, and that 36 percent suffered from stunted growth.

To Paulo Pinheiro, head of the UN-mandated Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, the government’s denial of aid access amounts to “deliberate starvation of the civilian population.”

The Eastern Ghouta insurgency is dominated by two rival factions, whose mutually hostile relationship was shaped by a long, bitter and polarising process of factional consolidation through infighting.

The northern city of Douma and eastern parts of the enclave are run by the Islam Army, a large Salafi-inspired Islamist group. The outskirts of Damascus, in the enclave’s southwest, are dominated by Failaq al-Rahman, a Free Syrian Army-branded group with some ties to the Muslim Brotherhood.

Both factions rule their areas in an authoritarian fashion, enforcing conservative religious laws and repressing dissidents who show support for the government or for their local rivals.

There are also two smaller Islamist factions, both of which are opportunistically aligned with Failaq al-Rahman due to a shared history of conflict with the Islam Army.

On the northwestern end of the enclave, the Harasta neighbourhood is run by a local franchise of Ahrar al-Sham, a Salafi faction whose main area of influence is in northern Syria.

The jihadi group Tahrir al-Sham, which emerged out of Syria’s al-Qaeda franchise, also has a presence in the enclave. Though it is the most powerful rebel faction in northern Syria, Tahrir al-Sham’s Ghouta wing seems small in comparison with the Islam Army or Failaq al-Rahman. To survive, it operates in Failaq al-Rahman-dominated areas after being violently attacked by the Islam Army last year.

In interviews with IRIN, Failaq al-Rahman officials have denied any alliance with Tahrir al-Sham, and clashes between the two groups have been known to occur. However, signs point to some form of defensive pact between these two groups against the Islam Army.

Due to its anti-Western agenda and terrorism designations, Tahrir al-Sham tends to be given outsized importance in the rhetoric of the pro-Assad camp, as when Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov recently claimed that Tahrir al-Sham "runs the show" in Eastern Ghouta.

In the past week, the air campaign against Eastern Ghouta has reached unprecedented levels, with hundreds killed in the enclave while rebels fire mortars into Damascus. The pro-government Syrian daily al-Watan says a major ground offensive may begin in the coming week.

Reactions in Syria are, as always, deeply polarised.

Opposition sympathisers condemn the surging air strikes, with the Douma Local Council demanding international protection against what it terms a "genocidal campaign".

To many government supporters, however, an offensive to clear out rebels from Eastern Ghouta cannot come soon enough.

“This is a legitimate liberation process that is long due”, said Syrian member of parliament Fares al-Shehabi, who spoke to IRIN on Thursday afternoon. “No more Qaeda jihadis next to our capital!”

Though the fighting in Eastern Ghouta is at heart a military conflict over territory—not, as one might presume from overheated press commentary, a Srebrenica-style mass execution—civilians are bearing the brunt of the violence.

UN sources have documented 346 deaths and 878 injuries since early February, not counting combatants. The real figure is thought to be higher, and aerial bombardment is now escalating sharply.

According to Linda Tom, a Damascus-based spokeswoman for the UN’s emergency aid coordination body, OCHA, there were reports of over 200 killed and more than 500 wounded in the enclave on Tuesday and Wednesday alone.

According to an opposition tally seen by IRIN, a further 71 civilians lost their lives in Eastern Ghouta on Thursday, and a medical source speaking to IRIN listed 24 attacks on hospitals, clinics and Red Crescent centres since 18 February, including in Douma, Saqba, Jisreen, Harasta, Kafr Batna, and Beit Sawa.

The attacks on health facilities are particularly destructive, international aid organisations say.

“Wounded victims are dying only because they cannot be treated in time”, noted Marianne Gasser, the ICRC's head of delegation in Syria, in a 21 February statement where she demanded access for ICRC teams.

Although the rebels have much less firepower than the pro-regime side, their mortar and rocket fire into Damascus seems equally indiscriminate. OCHA’s Linda Tom tells IRIN that the UN received reports of 13 killed and more than 50 wounded in rebel shelling on Tuesday. Syrian state media reported another three dead and 22 wounded by mortars yesterday.

The government’s immediate aims are unclear. To retake the entire enclave may be the ultimate ambition, but al-Assad’s forces are likely to pursue interim goals such as seizing specific areas, decimating a particular faction, or mixing military assaults with temporary ceasefires and evacuation agreements.

As always when a government offensive looms, official rhetoric homes in on Tahrir al-Sham.

Russia led talks last autumn to force the jihadis to evacuate Eastern Ghouta to Idlib, following a model seen in several other besieged areas whereby armed fighters can chose between surrendering or accepting safe passage on buses to rebel-held territory in the north, accompanied by those civilians and family members who wish to join them. In return, Failaq al-Rahman reportedly asked for a new trade crossing near Mleiha or Harasta in order to reduce their reliance on Islam Army-controlled Wafideen. But these talks failed, and the current offensive seems to aim much higher.

According to the al-Assad-friendly Beirut daily al-Akhbar, the government now wants both Tahrir al-Sham and Failaq al-Rahman sent to Idlib. Russian and Egyptian negotiators have reportedly sought to stitch together an agreement along these lines, with Russia warning it will back a ground offensive unless a deal is reached. But despite "marathon" negotiations, there seems to have been no breakthrough.

“The experience gained in Aleppo, when an agreement was reached with militants on their organized exodus, can be used in Eastern Ghouta”, Lavrov said earlier this week.

That would seem to be sugar-coating events in Aleppo, which rather stands out as a model to be avoided. Aleppo’s rebels and their international backers rejected all talk of a negotiated handover for months, despite being overwhelmingly outgunned. Only after opposition defences had crumbled and civilians were fleeing in all directions did they agree to a deal, which resulted in a hasty, scrambled, and chaotic evacuation of both rebel fighters and about 30,000 of the remaining civilians, most of whom were apparently never given a choice over whether to stay or leave. It was later described by the UN’s Commission of Inquiry as "forced displacement", a war crime.

The Eastern Ghouta enclave’s fate appears to be sealed. A safe exit arrangement for armed rebels and others who refuse or are unable to live under al-Assad may therefore be the least harmful solution for civilians. However there is a thin line between that outcome and violence that spins out of control into mass expulsion.

Even if opposition defeat in Eastern Ghouta ultimately seems certain, there are still many military and political paths to that end—some fast, some slow, and some more damaging to innocent people than others.

President Bashar al-Assad’s forces and his Russian allies seem poised for a major ground offensive on the besieged insurgent enclave. What do we know?

What is the Eastern Ghouta enclave and why does it matter?

Ghouta is an agricultural region ringing Damascus, part of which has succumbed to urban expansion and slum housing in recent decades. In Eastern Ghouta, anti-Assad insurgents have been besieged by the Syrian army since spring 2013.

Recent UN estimates put the enclave’s population at around 393,000, with the UN’s top official in Syria, Ali al-Zatari, saying 272,500 inhabitants are in need of humanitarian assistance. About a third of Eastern Ghouta’s population is internally displaced, including people who have fled from Damascus.

These figures remain uncertain, and previous UN population estimates for besieged areas in Syria have at times proven too high, notably in eastern Aleppo. But although Syrian loyalist or opposition sources may provide lower or higher numbers, the UN records remain the only widely-recognised figures available.

The area is important to the Syrian government, since it encompasses the eastern suburbs of the capital. Large, well-defended, and within mortar range of central Damascus, where the Old City and other neighbourhoods have suffered from rebel shelling, Eastern Ghouta has been a severe irritant to the loyalist camp for years.

Can civilians leave the enclave?

Leaving the enclave has long been impossible for most inhabitants, though there are exceptions. A small number of inhabitants, including public employees, are reportedly allowed to come and go through an agreed and mutually supervised checkpoint at Wafideen, near Douma, though it is a risky passage due to land mines, sniper fire, and the aggressive and unpredictable behaviour of both government and rebel forces.

.

Syrian authorities recently dropped fliers over Eastern Ghouta telling civilians to leave the area, but they have in the past refused entry for people trying to get out.

For example, the UN has tried for eight months to evacuate 500 severely ill or wounded civilians from Eastern Ghouta, including small children. The government refuses to let them out of the enclave, leading to the reported death of 22 of these patients so far.

A smaller group of around 35 patients was allowed out in December, albeit as part of a negotiated swap with detainees released by the rebels, rather than out of respect for humanitarian law. Both sides have made a habit of using prisoners of war and civilian hostages as negotiating chips.

Critics of al-Assad who are thinking of leaving are also fearful of being apprehended by his police forces, which have a decades-long history of arbitrary arrests, detainee abuse, and unlawful executions. Many of those who are apolitical or willing to take their chances with the regime remain concerned that they or their male relatives could be drafted into the army.

The rebels also restrict civilian movement. Amnesty International has noted that the Islam Army, which controls the opposition side of the Wafideen checkpoint, only allows select civilians to leave and has on occasion arrested people for simply asking permission to go.

According to REACH, a UN-backed initiative working on humanitarian reporting, the opposition groups have reportedly banned women, children, and men of fighting age from leaving the enclave, thereby preventing families from exiting together even if some members have been given free passage.

How does food get into Eastern Ghouta?

Humanitarian conditions inside Eastern Ghouta are extremely poor. Government shelling, infighting, and misrule by armed opposition groups play a part in that, but the most important reason is a blockade on food and humanitarian assistance imposed by the Syrian army.

How harshly the blockade is enforced has varied over the years. UN and Syrian Arab Red Crescent aid convoys are sometimes allowed in to prevent outright starvation, but permissions are rare and irregular. Aid officials say they are not permitted to deliver anywhere near the amount of food needed, and medical supplies are often stolen or sent back at government checkpoints.

By withholding humanitarian aid, the government has pushed up food prices and inflated the profit margins of a regime-connected businessman granted monopoly rights to trade via the Wafideen crossing, possibly in return for sharing the profits with the president’s entourage. Some rebel groups have been in on the deal: both regime figures and insurgent commanders have made money by taxing food at the expense of local civilians.

From 2014 until 2017, rebel-controlled smuggling tunnels brought in goods not permitted through Wafideen—including weapons and ammunition, but also food, medicine and fuel, which is needed to power electrical generators, water pumps and other basic infrastructure. In spring 2017, the Syrian army captured the tunnels. Since then, accumulating economic and infrastructural problems have diminished the area’s ability to cope with deprivation.

What is the current humanitarian situation?

Despite promises of improved humanitarian access as the main rebel groups signed Russian-brokered de-escalation deals last summer, the Syrian military began tightening the screws in late 2017.

In September, the government shut down even the for-profit food trade it had previously allowed through Wafideen. Since then, all but a handful of UN-organised aid convoys have been stopped by the authorities, thus engineering a severe civilian health crisis .

Recent WFP reporting indicates that prices in the enclave have grown by 140 percent since the Wafideen closure and are now six times higher than the national average. According to REACH, a bag of flat bread, which is a staple food in Syria, now costs 94 Syrian pounds in Damascus but 1,500 Syrian pounds in Eastern Ghouta.

Even before the effects of the current crisis were fully felt, humanitarian officials described Eastern Ghouta’s malnutrition levels as the worst ever recorded during the Syrian war. A November 2017 UN survey found that 11.9 percent of children under five were acutely malnourished, and that 36 percent suffered from stunted growth.

To Paulo Pinheiro, head of the UN-mandated Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, the government’s denial of aid access amounts to “deliberate starvation of the civilian population.”

Who are the rebels in Eastern Ghouta?

The Eastern Ghouta insurgency is dominated by two rival factions, whose mutually hostile relationship was shaped by a long, bitter and polarising process of factional consolidation through infighting.

The northern city of Douma and eastern parts of the enclave are run by the Islam Army, a large Salafi-inspired Islamist group. The outskirts of Damascus, in the enclave’s southwest, are dominated by Failaq al-Rahman, a Free Syrian Army-branded group with some ties to the Muslim Brotherhood.

Both factions rule their areas in an authoritarian fashion, enforcing conservative religious laws and repressing dissidents who show support for the government or for their local rivals.

There are also two smaller Islamist factions, both of which are opportunistically aligned with Failaq al-Rahman due to a shared history of conflict with the Islam Army.

On the northwestern end of the enclave, the Harasta neighbourhood is run by a local franchise of Ahrar al-Sham, a Salafi faction whose main area of influence is in northern Syria.

The jihadi group Tahrir al-Sham, which emerged out of Syria’s al-Qaeda franchise, also has a presence in the enclave. Though it is the most powerful rebel faction in northern Syria, Tahrir al-Sham’s Ghouta wing seems small in comparison with the Islam Army or Failaq al-Rahman. To survive, it operates in Failaq al-Rahman-dominated areas after being violently attacked by the Islam Army last year.

In interviews with IRIN, Failaq al-Rahman officials have denied any alliance with Tahrir al-Sham, and clashes between the two groups have been known to occur. However, signs point to some form of defensive pact between these two groups against the Islam Army.

Due to its anti-Western agenda and terrorism designations, Tahrir al-Sham tends to be given outsized importance in the rhetoric of the pro-Assad camp, as when Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov recently claimed that Tahrir al-Sham "runs the show" in Eastern Ghouta.

What will happen now?

In the past week, the air campaign against Eastern Ghouta has reached unprecedented levels, with hundreds killed in the enclave while rebels fire mortars into Damascus. The pro-government Syrian daily al-Watan says a major ground offensive may begin in the coming week.

Reactions in Syria are, as always, deeply polarised.

Opposition sympathisers condemn the surging air strikes, with the Douma Local Council demanding international protection against what it terms a "genocidal campaign".

To many government supporters, however, an offensive to clear out rebels from Eastern Ghouta cannot come soon enough.

“This is a legitimate liberation process that is long due”, said Syrian member of parliament Fares al-Shehabi, who spoke to IRIN on Thursday afternoon. “No more Qaeda jihadis next to our capital!”

How are civilians affected by the escalation?

Though the fighting in Eastern Ghouta is at heart a military conflict over territory—not, as one might presume from overheated press commentary, a Srebrenica-style mass execution—civilians are bearing the brunt of the violence.

UN sources have documented 346 deaths and 878 injuries since early February, not counting combatants. The real figure is thought to be higher, and aerial bombardment is now escalating sharply.

According to Linda Tom, a Damascus-based spokeswoman for the UN’s emergency aid coordination body, OCHA, there were reports of over 200 killed and more than 500 wounded in the enclave on Tuesday and Wednesday alone.

According to an opposition tally seen by IRIN, a further 71 civilians lost their lives in Eastern Ghouta on Thursday, and a medical source speaking to IRIN listed 24 attacks on hospitals, clinics and Red Crescent centres since 18 February, including in Douma, Saqba, Jisreen, Harasta, Kafr Batna, and Beit Sawa.

The attacks on health facilities are particularly destructive, international aid organisations say.

“Wounded victims are dying only because they cannot be treated in time”, noted Marianne Gasser, the ICRC's head of delegation in Syria, in a 21 February statement where she demanded access for ICRC teams.

Although the rebels have much less firepower than the pro-regime side, their mortar and rocket fire into Damascus seems equally indiscriminate. OCHA’s Linda Tom tells IRIN that the UN received reports of 13 killed and more than 50 wounded in rebel shelling on Tuesday. Syrian state media reported another three dead and 22 wounded by mortars yesterday.

How will this end?

The government’s immediate aims are unclear. To retake the entire enclave may be the ultimate ambition, but al-Assad’s forces are likely to pursue interim goals such as seizing specific areas, decimating a particular faction, or mixing military assaults with temporary ceasefires and evacuation agreements.

As always when a government offensive looms, official rhetoric homes in on Tahrir al-Sham.

Russia led talks last autumn to force the jihadis to evacuate Eastern Ghouta to Idlib, following a model seen in several other besieged areas whereby armed fighters can chose between surrendering or accepting safe passage on buses to rebel-held territory in the north, accompanied by those civilians and family members who wish to join them. In return, Failaq al-Rahman reportedly asked for a new trade crossing near Mleiha or Harasta in order to reduce their reliance on Islam Army-controlled Wafideen. But these talks failed, and the current offensive seems to aim much higher.

According to the al-Assad-friendly Beirut daily al-Akhbar, the government now wants both Tahrir al-Sham and Failaq al-Rahman sent to Idlib. Russian and Egyptian negotiators have reportedly sought to stitch together an agreement along these lines, with Russia warning it will back a ground offensive unless a deal is reached. But despite "marathon" negotiations, there seems to have been no breakthrough.

“The experience gained in Aleppo, when an agreement was reached with militants on their organized exodus, can be used in Eastern Ghouta”, Lavrov said earlier this week.

That would seem to be sugar-coating events in Aleppo, which rather stands out as a model to be avoided. Aleppo’s rebels and their international backers rejected all talk of a negotiated handover for months, despite being overwhelmingly outgunned. Only after opposition defences had crumbled and civilians were fleeing in all directions did they agree to a deal, which resulted in a hasty, scrambled, and chaotic evacuation of both rebel fighters and about 30,000 of the remaining civilians, most of whom were apparently never given a choice over whether to stay or leave. It was later described by the UN’s Commission of Inquiry as "forced displacement", a war crime.

The Eastern Ghouta enclave’s fate appears to be sealed. A safe exit arrangement for armed rebels and others who refuse or are unable to live under al-Assad may therefore be the least harmful solution for civilians. However there is a thin line between that outcome and violence that spins out of control into mass expulsion.

Even if opposition defeat in Eastern Ghouta ultimately seems certain, there are still many military and political paths to that end—some fast, some slow, and some more damaging to innocent people than others.

SYRIA: Nine civilians killed today in #EasternGhouta, 426 since Sunday: monitor @syriahr @AFP #Syria: image via Jean-Marc Mojon @mojobeirut, 23 February 2018

Remember that the children we see in #Ghouta have never known a life without fear... Seven years of this #Syria #Ghouta By @AFP @hamza_alajweh: image via Sophie McNeill @Sophiemcneill, 22 February 2018

epa editor's choice 23 February 2018: #SyriaBombing #EasternGhouta #Damascus #Syria Photo epa-efe / @badramamet: image via epa photos @epaphotos, 23 February 2018

“We were supposed to have surrendered by now,” he said at the end of the most intensive week-long barrage anywhere in Syria in the past three years.

“When we didn’t, the bombs were bigger, the planes more regular, and the injuries like nothing we’ve seen. All sent from Moscow.”

The Russian-led air blitz has been the sum of all fears for the besieged population on the ground. Up to 400,000 people, with nowhere to run, have been pinned down by Vladimir Putin’s air force as Syrian and Iranian-backed ground troops edge closer to the largest and most important opposition area anywhere south of Idlib.

For Assad and Putin, Ghouta is the key to controlling the capital, and winning the war. But outside the Syrian cauldron, friends and foes alike are starting to believe both men have miscalculated.

It is increasingly unclear how Moscow will recoup its investment in the world’s most complex conflict

Nearly 18 months into Russia’s intervention to prevent Assad’s defeat at the hands of rebel groups that were advancing on his heartland areas of Latakia and Tartous, it is increasingly unclear just how Moscow will recoup its investment in the world’s most complex and intractable conflict.

While it no longer appears Assad is in danger of falling, what remains of Syria looks nothing like the prewar country he used to rule. Central authority in the once-rigid police state has been subsumed several times over – first by opposition groups, and then by regional players also increasingly invested in shaping postwar outcomes in their own interests, which only partly align with what Putin wants. Protagonists on both sides are drowning in a swamp they did not see ahead.

Putin, in particular, is learning that Syria in its present form is ungovernable. His December claim of "victory" at a Russian airbase near Idlib has been followed by a dizzying series of events which, on the contrary, have drawn Russia further into the war. At the same time they have exposed the Assad regime’s near-total dependence on proxy support to hold its positions, let alone secure more gains.

The statement is looking every bit as premature as George W Bush’s claim of “mission accomplished”, made in a speech on the flight deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln in 2003 at the end of the war in Iraq. In attempting to showcase a superpower’s military strength, the former president instead exposed its diplomatic limitations.

Across Syria, and in the region itself, alliances that were more or less predictable are now splintered and opaque. A chessboard once easy to read could now outwit a grandmaster of global geopolitics.

From Ghouta north to the Turkish border, from Hama in the west to the oil-rich Deir ez-Zor in eastern Syria, where up to 200 advancing Russian mercenaries were killed by a US counterattack on 7 February, a new regional order is being fought out.

“And we will be trampled like mice under the feet of buffaloes,” said Ayman Thaer, a volunteer at an aid centre in Ghouta, where at least 500 peoole were killed this past week by Russian and Syrian bombs. “May God damn them all.”

Just how to balance the increasingly potent interests on display in Syria is bedevilling all who have tried.

“The only winner so far is Iran,” said Bassam Barabandi, a former Syrian diplomat who defected from the regime in mid-2013. “It achieves what it wants without too much noise. Iran enjoys Russian-American conflict because it makes Russia more dependent on Iran to survive.”

The clash between the US and Russian mercenaries sent to Syria was kept quiet by Moscow, which – in different circumstances – would have complained bitterly if 200 of its citizens had been killed by a rival power. For Putin to admit even that the men were there would have belied his claim of victory and withdrawal from a war that no longer needed him. Acknowledging they were advancing on an oil refinery held by US Kurdish proxies would have been an equally tough sell, at a time when securing Syria from the threat of terrorism and US hegemony remains the official narrative.

US intelligence officials believe the company that recruited the Russians – the Wagner Group – is controlled by a Putin confidant, Yevgeniy Prigozhin.

Also staking its claim in Deir ez-Zor is Iran, with which Russia has partnered to ensure that what remains of the anti-Assad opposition can no longer win the war. Russian officials have complained to counterparts in Turkey that Iranian aims are increasingly at odds with their own.

A senior Turkish diplomat told the Observer Moscow feels especially threatened by what it sees as Iran’s determination to build a state security structure in Damascus modelled on its Revolutionary Guard Corps – the most powerful institution in Tehran 40 years after the Islamic Revolution. “But how can they stop them?”, the diplomat said. “Putin won’t have it his own way from here. And we can see [the Russians] getting irritated by it.”

From mid-2016, Putin started to draw Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan into an alliance with Iran which aimed to bring the war to an end on terms to Assad’s benefit.

The alliance was a death knell for an opposition that Turkey backed in the north. It culminated in a trilateral summit in Sochi last November, which was supposed to deliver a diplomatic victory that had eluded all others – and at the same time sideline a moribund UN-backed process. It was an embarrassing failure. Diplomacy has since collapsed and violence, first in Idlib and now in Ghouta, is nearing record levels.

Turkey has reframed its involvement in the war, started to oust Assad but now aimed at keeping Kurds from controlling the Turkey-Syria border. Last month Turkey sent troops – and Arab militia – into the Syrian border enclave of Afrin to fight Kurdish militias. The move was quietly sanctioned by Moscow. But in the past week, forces loyal to Assad were allowed into Afrin to counter the Turks.

Russia’s position on this development is unclear. “Russia always says it does not have the leverage on Assad the way the world thinks. This is true,” said Barabandi. “Iran has more influence on Assad. Put simply, Iran came to stay in all of Syria and to challenge the US by threatening Israel. Syria will be the theatre in any coming war between Hezbollah and Iran against Israel. At least this is what the Iranians are hoping.

“And Iran is happy that Russia has taken the lead in Syria and let them empower their forces without distraction. None of the players trust each other and what we see is short-term contracts that may shift at any time. The only thing they have in common is they want the US to be out of Syria.”

Meanwhile, Russia – which had high hopes that Syria would be a launching pad for a new power projection, ensuring Assad’s survival and securing its own lead role in shaping order in the region, and perhaps far beyond – is focusing on more short-term gains. “As we helped the brotherly Syrian people, we tested over 200 new types of weapons,” said Vladimir Shamanov, head of the Russian Duma’s defence committee. “Today our military-industrial complex made our army look in a way we can be proud of.”

With little to bank, Russia will continue to find its veto at the UN Security Council a potent tool. It has vetoed UN resolutions against Assad 11 times.

Civil defence rescue workers help a man from a shelter after an air strike in the besieged town of Douma in eastern Ghouta, 22 February 2018: photo by Reuters, 22 February 2018

Moscow mired in Syria as Putin’s gameplan risks a deadly ending: Russian leader’s gamble backing Bashar al-Assad increasingly looks miscalculated: Martin Chulov, The Observer, 24 February 2018

From his spot in the ruins of east Ghouta, Arif Othman sees the

current phase of Syria’s war as brutally simple. The longer he holds out

against Bashar al-Assad and his allies, the worse it will get – especially at the hands of the Russians.

“We were supposed to have surrendered by now,” he said at the end of the most intensive week-long barrage anywhere in Syria in the past three years.

“When we didn’t, the bombs were bigger, the planes more regular, and the injuries like nothing we’ve seen. All sent from Moscow.”

The Russian-led air blitz has been the sum of all fears for the besieged population on the ground. Up to 400,000 people, with nowhere to run, have been pinned down by Vladimir Putin’s air force as Syrian and Iranian-backed ground troops edge closer to the largest and most important opposition area anywhere south of Idlib.

For Assad and Putin, Ghouta is the key to controlling the capital, and winning the war. But outside the Syrian cauldron, friends and foes alike are starting to believe both men have miscalculated.

It is increasingly unclear how Moscow will recoup its investment in the world’s most complex conflict

Nearly 18 months into Russia’s intervention to prevent Assad’s defeat at the hands of rebel groups that were advancing on his heartland areas of Latakia and Tartous, it is increasingly unclear just how Moscow will recoup its investment in the world’s most complex and intractable conflict.

While it no longer appears Assad is in danger of falling, what remains of Syria looks nothing like the prewar country he used to rule. Central authority in the once-rigid police state has been subsumed several times over – first by opposition groups, and then by regional players also increasingly invested in shaping postwar outcomes in their own interests, which only partly align with what Putin wants. Protagonists on both sides are drowning in a swamp they did not see ahead.

Putin, in particular, is learning that Syria in its present form is ungovernable. His December claim of "victory" at a Russian airbase near Idlib has been followed by a dizzying series of events which, on the contrary, have drawn Russia further into the war. At the same time they have exposed the Assad regime’s near-total dependence on proxy support to hold its positions, let alone secure more gains.

The statement is looking every bit as premature as George W Bush’s claim of “mission accomplished”, made in a speech on the flight deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln in 2003 at the end of the war in Iraq. In attempting to showcase a superpower’s military strength, the former president instead exposed its diplomatic limitations.

Across Syria, and in the region itself, alliances that were more or less predictable are now splintered and opaque. A chessboard once easy to read could now outwit a grandmaster of global geopolitics.

From Ghouta north to the Turkish border, from Hama in the west to the oil-rich Deir ez-Zor in eastern Syria, where up to 200 advancing Russian mercenaries were killed by a US counterattack on 7 February, a new regional order is being fought out.

“And we will be trampled like mice under the feet of buffaloes,” said Ayman Thaer, a volunteer at an aid centre in Ghouta, where at least 500 peoole were killed this past week by Russian and Syrian bombs. “May God damn them all.”

Just how to balance the increasingly potent interests on display in Syria is bedevilling all who have tried.

“The only winner so far is Iran,” said Bassam Barabandi, a former Syrian diplomat who defected from the regime in mid-2013. “It achieves what it wants without too much noise. Iran enjoys Russian-American conflict because it makes Russia more dependent on Iran to survive.”

The clash between the US and Russian mercenaries sent to Syria was kept quiet by Moscow, which – in different circumstances – would have complained bitterly if 200 of its citizens had been killed by a rival power. For Putin to admit even that the men were there would have belied his claim of victory and withdrawal from a war that no longer needed him. Acknowledging they were advancing on an oil refinery held by US Kurdish proxies would have been an equally tough sell, at a time when securing Syria from the threat of terrorism and US hegemony remains the official narrative.

US intelligence officials believe the company that recruited the Russians – the Wagner Group – is controlled by a Putin confidant, Yevgeniy Prigozhin.

Also staking its claim in Deir ez-Zor is Iran, with which Russia has partnered to ensure that what remains of the anti-Assad opposition can no longer win the war. Russian officials have complained to counterparts in Turkey that Iranian aims are increasingly at odds with their own.

A senior Turkish diplomat told the Observer Moscow feels especially threatened by what it sees as Iran’s determination to build a state security structure in Damascus modelled on its Revolutionary Guard Corps – the most powerful institution in Tehran 40 years after the Islamic Revolution. “But how can they stop them?”, the diplomat said. “Putin won’t have it his own way from here. And we can see [the Russians] getting irritated by it.”

From mid-2016, Putin started to draw Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan into an alliance with Iran which aimed to bring the war to an end on terms to Assad’s benefit.

The alliance was a death knell for an opposition that Turkey backed in the north. It culminated in a trilateral summit in Sochi last November, which was supposed to deliver a diplomatic victory that had eluded all others – and at the same time sideline a moribund UN-backed process. It was an embarrassing failure. Diplomacy has since collapsed and violence, first in Idlib and now in Ghouta, is nearing record levels.

Turkey has reframed its involvement in the war, started to oust Assad but now aimed at keeping Kurds from controlling the Turkey-Syria border. Last month Turkey sent troops – and Arab militia – into the Syrian border enclave of Afrin to fight Kurdish militias. The move was quietly sanctioned by Moscow. But in the past week, forces loyal to Assad were allowed into Afrin to counter the Turks.

Russia’s position on this development is unclear. “Russia always says it does not have the leverage on Assad the way the world thinks. This is true,” said Barabandi. “Iran has more influence on Assad. Put simply, Iran came to stay in all of Syria and to challenge the US by threatening Israel. Syria will be the theatre in any coming war between Hezbollah and Iran against Israel. At least this is what the Iranians are hoping.

“And Iran is happy that Russia has taken the lead in Syria and let them empower their forces without distraction. None of the players trust each other and what we see is short-term contracts that may shift at any time. The only thing they have in common is they want the US to be out of Syria.”

Meanwhile, Russia – which had high hopes that Syria would be a launching pad for a new power projection, ensuring Assad’s survival and securing its own lead role in shaping order in the region, and perhaps far beyond – is focusing on more short-term gains. “As we helped the brotherly Syrian people, we tested over 200 new types of weapons,” said Vladimir Shamanov, head of the Russian Duma’s defence committee. “Today our military-industrial complex made our army look in a way we can be proud of.”

With little to bank, Russia will continue to find its veto at the UN Security Council a potent tool. It has vetoed UN resolutions against Assad 11 times.

.

Civil defence rescue workers help a man from a shelter after an air strike in the besieged town of Douma in eastern Ghouta, 22 February 2018: photo by Reuters, 22 February 2018

Negotiations continue between rebels and the Syrian Army, but the bombardment of Ghouta won't stop any time soon: Ghouta will fall. That is the message. And when it falls, Idlib must surely be next. And then the Syrians must decide how to break the US-Kurdish hold on Raqqa. Robert Fisk, The Independent, 24 February 2018

Syria

continues to mass its armed forces around the east Ghouta enclave of

Damascus, including army units commanded by President Bashar

al-Assad’s brother Maher and by Colonel Soheil Hassan, the “Tiger”

whose military victories across the country have made him legendary

among Assad’s supporters.

Instead of moving by night - the traditional tactic adopted

by the army in the war - vast quantities of Syrian armour have been

humming along the highways to the capital in broad daylight from Aleppo

and Homs in the north, from Deraa in the south, and from the countryside

of Damascus itself. The Syrian authorities want them to be seen, to

show the Islamist rebels of Ghouta know how their battle will end.

Despite Russia’s

veto at the UN on Thursday night, however, negotiations have continued

between three rebel groups and the Syrian army - under the direct

mediation of the Russians - to establish “humanitarian corridors” and

“escape routes” for the tens of thousands of civilians trapped inside

Ghouta, the vast area of suburban slums and farmland held by Islamist

and other rebel groups since 2013. Almost identical talks took place

between Islamists and the government over eastern Aleppo before its fall

in December 2016. Bloodshed and negotiations have long been a feature

of the Syrian war.

But

despite all the West’s rhetoric - and the UN’s constant refrain that

the civilians of eastern Ghouta are experiencing "hell on earth" - the

massive Syrian and Russian bombardment is going to continue. The

Islamist Nusrah faction, the “child” of al-Qaeda

of 9/11 infamy, appears to be more reluctant to surrender to the

Syrians - even if allowed to leave with its light weapons - than Saudi

Arabia’s favourite militia, the Jaish al-Islam, or Qatar’s proxy “Rahman

Legion”. There are even suggestions that the Saudi and Qatari supported

factions are arguing with each other - even now, inside

Ghouta - about the Gulf dispute between the Saudis and Qataris.

There appears to be no such disunity among their enemies.

The Presidential Guard is on the edge of Ghouta, and the Syrians have

brought their 14th Division (Special Forces) to the suburbs. Maher

Assad’s 4th Armoured Division, based in Damascus, is positioned on the

perimeter, as is the military’s 7th Division, and troops belonging to

units commanded by Colonel “Tiger” Soheil Hassan.

Given the multitude of army regiments around Ghouta, Hassan

cannot be the overall commander, a post which remains diplomatically

undefined. But the convoys of tanks, armoured vehicles, field guns and

trucks pouring in daylight towards Damascus – and enthusiastically

captured on film by government photographers – is meant to be seen.

Ghouta will fall. That is the message. From within the

Syrian military, there are attempts to explain the ruthlessness of the

assault. Thousands of soldiers have been killed in the battles around

Ghouta since 2013; vast military “resources” – the word the army uses –

have been poured into this battle over the years. Most of the car bomb

attacks in Damascus and the constant shelling across the centre of the

capital for the past four years have come from Islamist forces in

Ghouta, especially from the Douma district. Of course, there are the

usual explanations from artillery officers: of “surgical” strikes, of

rebels hiding in hospitals and using civilians as “human shields”; but

these are words the world has heard before – from the Americans about

Mosul and Afghanistan, from the Israelis about Gaza, and the Russians

about Chechnya.

And pictures, as usual, speak louder than words. While the

footage from eastern Ghouta pointedly fails to show the armed Islamists

who are fighting in the enclave, there is no reason to doubt the

suffering of the civilians. And some of these civilians, it should be

remembered, will inevitably be relatives of the very Syrian soldiers who

are planning to storm Ghouta; there were many Syrian military personnel

who captured eastern Aleppo in 2016 whose own families also lived

there.

But Ghouta is experiencing a different sort of siege, one

that has no precedent in size during this war. “Shock and awe” – or

shock and terror – is what Syria’s enemies are supposed to experience.

The Russian and Syrian air attacks are proof of that. Even if maps look

simple on television screens, wars are infinitely more chaotic. Think of

the effect of a brick hitting the windscreen of a car, of the dozens of

fractures across the glass; that is what Syrian military maps look

like.

It is now being said that if the first Syrian advance into

Ghouta moves against areas controlled by al-Nusrah, it means that the

al-Qaeda fighters are being more stubborn in the negotiations than the

other two major groups. They will suffer first, along with the civilians

of course. This is the inevitable lesson of this terrifying war. The

Syrians, along with Iraqi militias and Hezbollah, do indeed have plans

for the overrunning of rebel-held Ghouta. And after this demonstration

of firepower, how could the Syrians and Russians stop now? If they did,

who would believe the message of the next siege? In northwestern Idlib,

for example. Or in the towns around it.

And so, when Ghouta falls, Idlib must surely be next. And

then the Syrians must decide how to break the US-Kurdish hold on Raqqa –

perhaps that is one reason why pro-Syrian forces have now gone to the

rescue of the Kurds in the northern province of Afrin, to drive a

further wedge between the Turks and the Americans, and force Washington

to abandon its Kurdish allies on the Euphrates.

It is painful to remember how these huge landscapes of river

and desert and mountainside lived in peace for a century – their

societies straitjacketed, of course, and without justice – before the

bloodbath. Ghouta receives the waters of five rivers, and the 1912

French edition of Baedeker’s travel handbook to “Syria and Palestine”

describes how the tributaries flowing into the sands to the east

conferred upon Ghouta the name of “Lakes of the Prairies”. But that was

the old Syria.

During searching of survivors under rubble, #Douma #EasternGhouta #Damascus #Syria #SaveGhouta @SCDrifdimashq #Douma @SyriaCivilDef @SyriaCivilDef: image via Mohammed Badra @badramamet, 23 February 2018

The life of #WhiteHelmets volunteers #SaveGhouta #volunteers #Rescue #Ghouta @SyriaCivilDef @ActForGhouta: image via Mohammed Badra @badramamet, 24 February 2018

The life of #WhiteHelmets volunteers #SaveGhouta #volunteers #Rescue #Ghouta @SyriaCivilDef @ActForGhouta: image via Mohammed Badra @badramamet, 24 February 2018

The life of #WhiteHelmets volunteers #SaveGhouta #volunteers #Rescue #Ghouta @SyriaCivilDef @ActForGhouta: image via Mohammed Badra @badramamet, 24 February 2018

A new wave of bombs has struck Syria's besieged town of Douma in eastern Ghouta #Syria @Badramamet @epaphotos: image via Sunday Times Pictures @STPictures, 23 February 2018

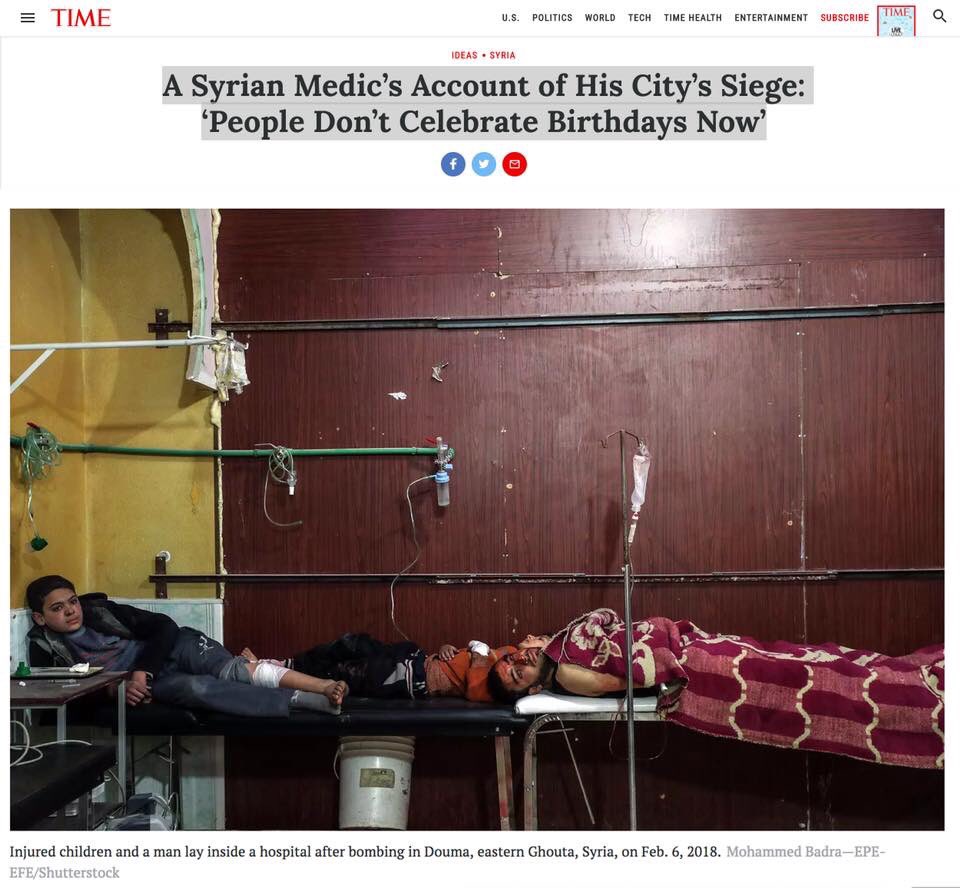

#syria #Douma #EasternGhouta @TIME @epaphotos: image via Mohammed Badra @badramamet, 22 February 2018

A new wave of bombs has struck Syria's besieged town of Douma in eastern Ghouta #Syria Photo @BassamKhabieh @reuterspictures: image via Sunday Times Pictures @STPictures, 23 February 2018

Life in #EasternGhouta

basements - 'It's very, very cold -- I tried to fix up a stove and bring

it into the tent at night so we can stay warm but we started

suffocating' #EasternGhouta: image via Jean-Marc Mojon @mojobeirut, 22 February 2018

Many residents of #EasternGhouta have pitched tents in their basements because of constant bombardment @AFPphoto by @abdfree2 #Syria: image via Jean-Marc Mojon @mojobeirut, 22 February 2018

46 people killed in #EasternGhouta today, 403 since Sunday (monitor) @AFPphoto by @abdfree2 #Syria: image via Jean-Marc Mojon @mojobeirut, 22 February 2018

GHOUTA UPDATE: The death toll in #EasternGhouta today rises to 19, according to #syriahr, bringing to 368 the number of people killed since Sunday @AFP #Syria: image via Jean-Marc Mojon @mojobeirut, 22 February 2018

Improvised classroom in #EasternGhouta basement @AFPphoto by @abdfree2 #school #children #Syria: image via Jean-Marc Mojon @mojobeirut, 23 February 2018

UPDATE New air strikes on the Syrian rebel enclave of Eastern Ghouta takes the civilian death toll from seven days of devastating bombardment to more than 500: image via AFP news agency @AFP, 24 February 2018

Death toll for today's rocket fire and air strikes on #EasternGhouta rises to 36: monitor @AFP #Syria #Damascus - Total since Sunday is 385: image via Jean-Marc Mojon @mojobeirut, 22 February 2018

Many residents of #EasternGhouta have pitched tents in their basements because of constant bombardment @AFPphoto by @abdfree2 #Syria: image via Jean-Marc Mojon @mojobeirut, 22 February 2018

46 people killed in #EasternGhouta today, 403 since Sunday (monitor) @AFPphoto by @abdfree2 #Syria: image via Jean-Marc Mojon @mojobeirut, 22 February 2018

GHOUTA UPDATE: The death toll in #EasternGhouta today rises to 19, according to #syriahr, bringing to 368 the number of people killed since Sunday @AFP #Syria: image via Jean-Marc Mojon @mojobeirut, 22 February 2018

Improvised classroom in #EasternGhouta basement @AFPphoto by @abdfree2 #school #children #Syria: image via Jean-Marc Mojon @mojobeirut, 23 February 2018

UPDATE New air strikes on the Syrian rebel enclave of Eastern Ghouta takes the civilian death toll from seven days of devastating bombardment to more than 500: image via AFP news agency @AFP, 24 February 2018

Death toll for today's rocket fire and air strikes on #EasternGhouta rises to 36: monitor @AFP #Syria #Damascus - Total since Sunday is 385: image via Jean-Marc Mojon @mojobeirut, 22 February 2018

Eastern Ghouta 24 February 2018: image via Ammar Sulaiman @AmmarSulaiman91, 24 February 2018

Eastern Ghouta 24 February 2018: image via Ammar Sulaiman @AmmarSulaiman91, 24 February 2018

25 February 2018

From his spot sizzled in Les Miserables

The ghost of electricity howls in the bulbs

Of her face, and as I turned the corner

They were by my side, Los Invisibles, the third

Who walks beside and the first two, who appeared

Out of the chalklike dust after the air strike

The ghost of electricity howls in the bulbs

Of her face, and as I turned the corner

They were by my side, Los Invisibles, the third

Who walks beside and the first two, who appeared

Out of the chalklike dust after the air strike

No comments:

Post a Comment