The machair, towards West Beach, Isle of Berneray, Outer Hebrides: photo by hazelisles, 11 June 2006

......On the Western Seaboard of South Uist

......Los muertos abren los ojos a los que viven

I found a pigeon's skull on the machair,

All the bones pure white and dry, and chalky,

But perfect,

Without a crack or a flaw anywhere.

At the back, rising out of the beak,

Were domes like bubbles of thin bone,

Almost transparent, where the brains had been

That fixed the tilt of the wings.

Storm surf at Port Nis, Northern Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland: photo by Chris Sharatt, 30 March 2010

Atlantic surf hits shore at Port Nis, Northern Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland: photo by Chris Sharatt, 30 March 2010

Bird skull: C. William Beebe, from The Bird: Its Form and Function, 1906 (image by L. Shyamal, 2 September 2007)

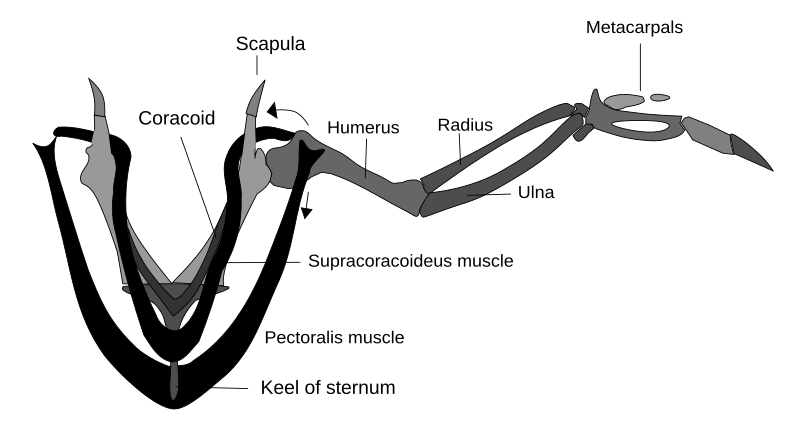

Wing muscles of bird. The supracoracoideus works using a pulley-like system to lift the wing while the pectorals provide the powerful downstroke: image by L. Shyamal, 10 December, 2007, based on J.R. Hincliffe and D. R. Johnson: The Development of the Invertebrate Limb, 1980

Flowering machair, hills of South Uist, Outer Hebrides, Scotland: photo by Tim Niblett, 1995

Hugh MacDiarmid memorial near Langholm, Dumfriesshire, Scotland. Made of cast iron, in the form of a large open book depicting images from MacDiarmid's writings: photo by R. Matthews, September 2006

Hugh MacDiarmid (1892-1978): Perfect, from The Islands of Scotland, 1939

15 comments:

A bit of personal history with this sweet little number.

When I was one and twenty, the editor of a new edition of the Faber Book of Modern Verse, capitalizing on my youthful eagerness, loaded me down with an armload of slim volumes of verse he did not have time to consider himself, and asked that I let him know if there was something necessary in there that he was missing.

I nominated "Perfect".

It's a perfect poem, really, in many ways.

For example, it stands as perhaps the outstanding example in modern poetry of the complicated workings of the collective accidental unconscious (as in, "it jumped into my hand, honest".)

I was about to write that -- that the poem is Perfect. It is also perfectly paired with the images. I had no idea that wave shapes (especially), mountain shapes and cloud shapes so closely resembled the shape of birds' skulls. All I know about Hugh MacDiarmid is this and what I read in his Wikipedia biography, which is pretty wild, really. It's odd -- you sort of stumble into a field of words and pictures arrayed on a page (looking like so many other pages you've seen)and you have absolutely no idea where you'll end up. This was a lovely addition to a "waiting" morning. Curtis

Curtis,

What's particularly curious about this precisely constructed little ship-in-a-bottle of a poem, which seems to penetrate through its own language by some mysterious force exerted inward (as through the three knob-like occipital lobes of the avian brain, perhaps?), is that all its bits and parts have been collected (perhaps after the fashion of the hunting-and-gathering of a bower bird?) from "external" sources (see that extremely interesting link I've given), leaving the poet himself missing in action at the center, a perfect vacancy, projecting an absence of affect as dry and clean as bone.

soothing images...love the green!! ...beautiful words!!

I, too, appreciate the symmetry of the images with the verse. In recent years, I've grown especially sensitive to this sensory overlap. Which is funny, since what child never played the game of naming the clouds? We forget perfection, which is perhaps fitting.

Perfect vertical juxtaposition.

I'm too tired probably to write clearly now, but not to have absorbed what's recounted in that page about Perfect. "Perfect vacancy" is good. The question of plagiarism is always interesting to consider because it prompts a number of vital questions, opening and closing various doors. MacDiarmid's poem is clearly not "plagiarized" (a highly negative term) in any sense from anyone. The poet has completely transformed, consciously or unconsciously, "found" material and created (and shared) something original and vital. Real plagiarism sneaks around in a mask, sullies everything in its vicinity and seeks VIP credentials and free drinks. Curtis

Hugh MacDiarmid -- his real name by the way, was Christopher Murray Grieve, the pen-name a fabrication of his poet identity -- was a great self-inventor as well as a great inventor.

In his early books he fabricated a curious "Synthetic Scots", a version of a "Lallans" dialect conflated out of bits of old and not so old Scots vernacular mixed with neologisms and laid over a modern English grammatical structure. Skeptics and purists called it Plastic Scots. Seen from this vantage, there appears an element of Modernism and Joyce in the project. The poems writ in it have a one-off feeling. It's quite wonderful, but perhaps an acquired taste. In any case the intensely Anglophobic MacDiarmid eventually if reluctantly gave it over and went back to writing in English.

MacDiarmid was a Communist and a Scottish nationalist -- but both parties threw him out for belonging to the other.

He was unashamed and unapologetic by nature. When charged with the direct copying of the Glyn Jones passage, he went ahead and put "Perfect" in his Collected Poems anyway. Jones accepted the situation at that. To paraphrase Marvell on Cromwell, To enclose was wiser than to oppose, with MacDiarmid.

Among the defiant contradictions of MacDiarmid was an insistence that poetry had to be born not out of the imagination but out of direct observation. And yet here we see a poem that qualifies as pure construction -- an assemblage, in effect.

Yet the poem does not feel unfelt; indeed the expressiveness is palpable. There's an enlarging sense of wonder, mortality, nature, eternity. One recalls the gravedigger scene in Hamlet. The fact that the poet derived the words of his poem verbatim from the Glyn Jones story; that he lifted the epigraph from a line quoted by a biographer of Cunninghame Graham (the line from the Spanish play La Celestina had been inscribed on the memorial of the latter's wife, on remote Inchmahone); and that, in his crowning act of audacious aesthetic cunning, with the unwitting assistance of the naturalist Seton Gordon ("Along the western seaboard... in the green machair"), he relocated the setting of the scene from Jones' Wales to Seton Gordon's South Uist -- it might be best to view all this "evidence" not from a forensic POV but as interesting compositional detail. Someone always has to do the finding, the selective extracting, and the putting together. It is rare indeed, as we know, that anyone writes anything that does not contain words that have been out on the town before. As Virginia Woolf once ruefully acknowledged, you never know where they might have been.

Visiting Scotland in 2005, I was struck by how wild and unspoiled the country seemed. Of course it has its grey industrial places, but for the most part it resembled Mendocino County (without as many trees).

I thought: before the industrial age, most of the land surface of the earth went unexploited. Now the nicest parts of the open land in the world is gradually being roped off into little precincts we call parks--protected places.

Pre-industrial cultures thought of open country as chaotic and filled with dangers and jeopardies. But now that humankind is too successful, over-running everywhere and everything, such unspoiled places seem sad and even tragic. Where, for instance, would we be likely to put a monument to someone we revere like McDiarmid?

The best thing that could happen to the world would be to depopulate it by half. That might allow us to return to a world in which the openness we associate with the beauty and power of nature would reassert its presence in a way that parks and vacation-lands never can.

Once we realize that overpowering nature is not nearly as useful as understanding and respecting it, we might be on the way to some kind of balance with our immediate environment. But I'm not optimistic.

Over the past few months I've been satisfying my vicarious travel instincts by looking at a great many views of the extremely beautiful yet also carefully managed landscapes of the "wilder" parts of Scotland -- most recently, the Langholm district, where MacDiarmid came from.

But/and then, in historical terms, one recalls the "other" Scotland, of the old claustrophobic, begrimed Glasgow "closes", as captured once by Thomas Annan -- which Engels saw as the deepest pit of the hell of industrial capitalism.

But about that monument... Well, as you know, the monuments to the poets of this town are put in a place that may be symbolically fitting, if in an unintended way: that is, where they can be walked all over (Nancy Sinatra style).

It is strange wearing feather earrings and how they sound when they turn, dry and high tech. They are too light to make good earrings--lighter than hair.

They are a lot tougher than they look.

I had missed the Thomas Annan post and am very glad I tuned back in here to find it. The MacDiarmid monument is really, really lovely. As for the Glasgow closes, I'm glad I've seen these. We have close friends from Glasgow (they're music industry people; they live in LA now but still have mainly Scottish friends) and I believe the husband knows the grimmer Glasgow sights pretty well. He's a remarkable man, an average bass player who graduated to business roles which took him far from Glasgow for work, but he and all his friends are absolutely rooted in Scotland. He's part of the group and generation where everyone knows Lulu, a Glaswegian of course, really well because they all "came up" (and went down to London) together. Curtis

For an example of an early poem writ in what MacDiarmid called "my Scots" (set in some views of the Langholm area, where he dwelt into the mid 1930s):

Hugh MacDiarmid: Empty Vessel

Susan,

Oh for feathers of any kind, to not weigh one down ever, to always be scattered to the winds, without even the bother and tackiness of the urn.

Curtis,

What a gal, Talk about Scots pluck. One recalls her doing a balls-out cover of the Isely Brothers at Age Fifteen (yet)!

One fears she was Rangers, but one hopes -- Celtic.

How dare one say was. The verb would be is. And an OBE to boot.

Lulu Lives! Oh Lulu!

A beauty of a post. Thank you. MacDiarmid's "The Watergaw" I know through and through. A handful of others. And now, "Perfect", good word to end on.

Thank you, Donna. I think the poem provides one of those rare moments when the unnatural imperfection of the human somehow finds expression for the mute perfection of the natural and inhuman, and gives it voice. Impossible to explain exactly how this happens, but elements of luck and chance as well as of observation and receptivity must surely play a part. And of course all the benefits are ours.

Post a Comment