.

Portrait of Sir Richard Southwell: Hans Holbein the Younger, c. 1537; black and coloured chalks, brush in black and metal pen, 36.6 x 27.7 cm (Royal Collection, Windsor)

Looking through a book of drawings by Holbein I realize several moments of truth. A nose (a line) so nose-like. So line-like. And then I think to myself "so what?" It's not going to solve any of my problems. And then I realize that at the very moment of appreciation I have no problems. Then I decide that this is a pretty profound thought. And that I ought to write it down. This is what I have just done. But it doesn't sound so profound any more. That's art for you.

Sir Thomas Elyot: Hans Holbein the Younger, 1532-33; chalk, pen and brush on paper, 28.6 x 20.6 cm (Royal Collection, Windsor)

Lady Elyot: Hans Holbein the Younger, 1532-33; chalk, pen and brush on paper, 28 x 20.9 cm (Royal Collection, Windsor)

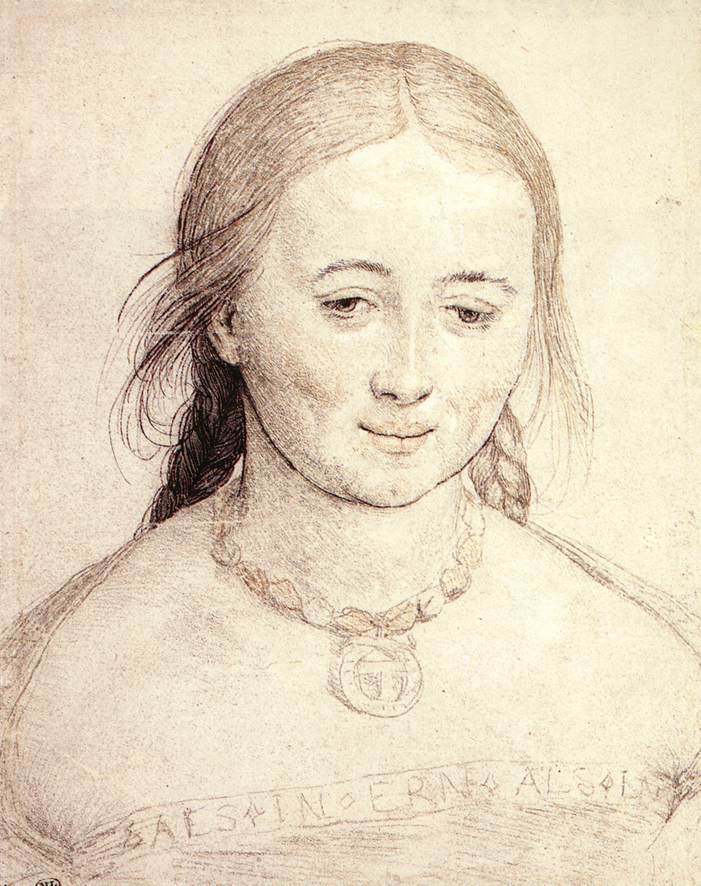

Portrait of Anna Meyer: Hans Holbein the Younger, c. 1526; black and coloured chalks, 39.1 x 27.5 cm (Kupferstichkabinett, Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel)

Jeanne de Boulogne, Duchess of Berry: Hans Holbein the Younger, 1524; black and coloured chalks, 39.6 x 27.5 cm (Kupferstichkabinett, Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel)

Jane Seymour: Hans Holbein the Younger, 1536-37; black and coloured chalks on paper, 50 x 28.5 cm (Royal Collection, London)

Sir Thomas More: Hans Holbein the Younger, 1527-28; black and coloured chalks on paper, 397 x 299 mm (Royal Collection, London)

Simon George of Quocote: Hans Holbein the Younger, 1536; pale pink priming, chalk with indian ink, 28,1 x 19,3 cm (Royal Collection, Windsor)

Portrait of Jakob Meyer zum Hasen: Hans Holbein the Younger, 1516; silverpoint, red chalk, and traces of black pencil on white coated paper, 281 x 190 mm (Kupferstichkabinett, Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel)

Portrait of Lady Mary Guildford: Hans Holbein the Younger, c. 1527; black and coloured chalks, 55,2 x 38,5 cm (Kupferstichkabinett, Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel)

Head of a Woman: Hans Holbein the Younger, c. 1522, drawing (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Studies of the Hands of Erasmus of Rotterdam: Hans Holbein the Younger, c. 1523; silverpoint, ruddle, and black chalks on white coated paper, 20.6 x 15.3 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Study for the Family Portrait of Sir Thomas More: Hans Holbein the Younger, c. 1527; pen and brush in black on top of chalk sketch, 38.9 x 52.4 cm (Kupferstichkabinett, Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel)

15 comments:

This is expressed so beautifully and says something that, if it isn't universally experienced, is certainly something I have felt. I think the first time was when I was shown (as a kid) a lithographic line drawing portrait of a woman's face by Henri Matisse. I think most people would call the piece an insignificant "nothing" Matisse. But it had (and has) the qualities and generates in the so-sensitized or inclined viewer the reaction Brainard describes. It's things like this that basically keep me going. I'm pleased to see this collection is being published. Curtis

Thanks, Tom. Beautiful work, and Joe always takes elegant simplicity to a new level.

Yes, I agree. I love the line drawings--the simple flow of lines in to image.

It sounded profound to me. Your words made me think of the truth that appears and disappears at the same time in a work of art. But I don't know how to explain it...

I love Holbein, thank you

Tom, that was always one of my favorite Joe pieces of writing (and your describing his writing as taking "elegant simplicity to a new level" is a great example of exactly that too!) but I am so grateful to you (and the internet) for making it possible to not just re present Joe's observation, but to do it with Holbein's drawings (in which the variety of "nose-like" lines seem to jump out of them thanks to the juxtaposition). So terrific to have you back making these revelatory pairings happen.

I'm not going to look at noses the same old way for a while. Well seen, well said!

I've been marveling for a long time at the genius of Holbein's draughtmanship. He began in the Gothic tradition, of which his father was a master, and his early "Germanic" style can be seen in the 1516 portrait of Jacob Meyer, the mayor of Basel, done when Hans the Younger was still an apprentice and only about 19. Ten years later, in the profile portrait sketch of Meyer's daughter Anna, we can see his own unique style emerging.

There is some dispute as to the procedures Holbein used in his portrait drawings, but some things are evident. He put a great deal of care into these preliminary sketches, which were quite exacting though apparently done fairly quickly, and seems to have employed certain methods of transferring the sketched images to wood when continuing on with the image in a painting.

Some think he used a "puzzle assembly" mode of transferring small sketched images to larger wood panels by the pouncing method, with a metal stylus.

It's known that some German artists, including Dürer employed tracing (perspective) apparati, optical and lens devices. David Hockney suggests Holbein employed a camera obscura. Others suggest that David Hockney was merely envious of Holbein's fabulous skills as a draughtsman, and that Holbein in his preliminary portrait sketches was drawing freely and straight "from life".

In any case, all artists use tools, and some of the tools Holbein used are indicated in the captions to the drawings I have presented.

What is certain is the fact that by means of line, Holbein captured quite precisely, with simplicity, elegance, and great lightness of touch, the individuality of his subjects -- without resort to flattery, drama or idealization.

Just those remarkable lines, always varying in weight but always strong and sure and extraordinarily revealing. The angling of the head, the set of the eyes and mouth, the cast of the gaze with its specific clarity and intensity, and, in particular, as Joe Brainard, another fine draughtsman, found so telling, the determining nose-line.

Holbein seems to employ line to see into the soul of a subject. All question of mechanical tools aside, it must have been that induplicable eye-to-hand skill which comprised the key tool Holbein used to locate, identify and capture the psychological singularity of his sitter. Joe saw this, I believe, and in the moment of recognition grasped a theory of art, of that kind founded in practise, in that inimitable manner of the artist as critic of the medium in which he works.

The respect for the dignity and the gravity of the human which makes Holbein's drawings so profoundly contemporary, in any age, is a wonder to behold, and Joe's "nose-line" explanation of how this miraculous artistic process works is at least as useful as any other I know of.

This gave me an occasion to speak at length with Jane about drawing this morning and, I think, awaken her to some things I know she'll enjoy and find valuable. Curtis

Curtis,

I hear tell that kids these days "learn drawing" on computers. My heavens. I can't imagine a childhood without pencil sketching on tablets, crayons, dimestore watercolor paint sets, that whole basic and elementary kit that went with the earliest attempts to picture the world, before machines did it for us.

Tom, that may be true to some extent in some art schools and classes, but kids in general are still doing it the old fashioned way in my experience. My two grandkids, now 9 and 13, and my youngest, now 14 and their many friends, as well as nephews and nieces and friends' kids etc. all constantly draw and cartoon and graffiti (as a verb) and sketch and comment on their twitter and texting etc. about each others' drawings etc. They just seem to seamlessly incorporate all the old techniques and tools in with the latest.

Great to see you with your nose back in the game, Tom. My thoughts and prayers go with you in your recovery. Profound or not, it's always great to great the reminder "it's not a competition"

Jane's school has an extremely good, sound and traditional art and music program. They mix new media (like digital photography, which is pretty much a given these days) in with the old, but kids are taught fundamentals very systematically, which is one of the things that gave rise to this morning's pre-school conversation, i.e., my daughter questioning why she was being required to draw and redraw that vase. This, naturally, led to further inquiry as to why her teacher was so eccentric, which promoted further colloquy about differences in personality types, artistic temperament, kindness/unkindness and the need for "lightening up." All in all, with the Holbein, a good morning. Curtis

A relief to hear the kids are still drawing without mechanical intervention.

__

"it's not a competition"

William, why is it that plain and simple truth sometimes seems so difficult for artists to wrap their minds around?

"it's not a competition"

Yes yes yes. This sums it up perfectly. Such a simple phrase & idea I don't see expressed nearly enough.

Brainard was able to flip the meditation into a wider view. A quest that is very much in keeping with the "top of my head coming off."

What is my mind thinking? Who dropped out of the tree house?

Post a Comment