.

President Lyndon B. Johnson listens to tape sent by his son-in-law Captain Charles

Robb. a Marine Corps company commander in Vietnam: photo by Jack E.

Kightlinger, 31 July 1968 (White House Office Photo Collection, Lyndon

Baines Johnson Library / National Archives and Records

Administration)

Gareth Porter: How LBJ Was Deceived on Gulf of Tonkin: War Pretext Incident to Justify Vietnam War

via Global Research, 6 August 2014

For most of the last five decades, it has been assumed that the Tonkin Gulf incident was a deception by Lyndon Johnson to justify war in Vietnam. But the U.S. bombing of North Vietnam on Aug. 4, 1964, in retaliation for an alleged naval attack that never happened, together with the Tonkin Gulf Resolution that followed, was not a move by LBJ to get the American people to support a U.S. war in Vietnam.

via Global Research, 6 August 2014

For most of the last five decades, it has been assumed that the Tonkin Gulf incident was a deception by Lyndon Johnson to justify war in Vietnam. But the U.S. bombing of North Vietnam on Aug. 4, 1964, in retaliation for an alleged naval attack that never happened, together with the Tonkin Gulf Resolution that followed, was not a move by LBJ to get the American people to support a U.S. war in Vietnam.

The real deception on that day was that Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara misled LBJ by withholding from him the information that the U.S. commander in the Gulf -- who had initially reported an attack by North Vietnamese patrol boats on U.S. warships -- had later expressed serious doubts about the initial report and was calling for a full investigation by daylight. That withholding of information from LBJ represented a brazen move to usurp the President’s constitutional power of decision on the use of military force.

McNamara’s deception is documented in the declassified files on the Tonkin Gulf episode in the Lyndon Johnson library, which this writer used to piece together the untold story of the Tonkin Gulf episode in a 2005 book on the U.S. entry into war in Vietnam. It is a key element of a wider story of how the national security state, including both military and civilian officials, tried repeatedly to pressure LBJ to commit the United States to a wider war in Vietnam.

Johnson had refused to retaliate two days earlier for a North Vietnamese attack on U.S. naval vessels carrying out electronic surveillance operations. But he accepted McNamara’s recommendation for retaliatory strikes on Aug. 4 based on reports of a second attack. But after that decision, the U.S. task force commander in the Gulf, Capt. John Herrick, began to send messages expressing doubt about the initial reports and suggested a “complete evaluation” before any action was taken in response.

McNamara had read Herrick’s message by mid-afternoon, and when he called the Pacific Commander, Admiral U.S. Grant Sharp Jr., he learned that Herrick had expressed further doubt about the incident based on conversations with the crew of the Maddox. Sharp specifically recommended that McNamara “hold this execute” of the U.S. airstrikes planned for the evening while he sought to confirm that the attack had taken place.

But McNamara told Sharp he preferred to “continue the execute order in effect” while he waited for “a definite fix” from Sharp about what had actually happened.

McNamara then proceeded to issue the strike execute order without consulting with LBJ about what he had learned from Sharp, thus depriving him of the choice of cancelling the retaliatory strike before an investigation could reveal the truth.

At the White House meeting that night, McNamara again asserted flatly that U.S. ships had been attacked in the Gulf. When questioned about the evidence, McNamara said, “Only highly classified information nails down the incident.” But the NSA intercept of a North Vietnamese message that McNamara cited as confirmation could not possibly have been related to the Aug. 4 incident, as intelligence analysts quickly determined based from the time-date group of the message.

LBJ began to suspect that McNamara had kept vital information from him, and immediately ordered national security adviser McGeorge Bundy to find out whether the alleged attack had actually taken place and required McNamara’s office to submit a complete chronology of McNamara’s contacts with the military on Aug. 4 for the White House indicating what had transpired in each of them.

But that chronology shows that McNamara continued to hide the substance of the conversation with Admiral Sharp from LBJ. It omitted Sharp’s revelation that Capt. Herrick considered the “whole situation” to be “in doubt” and was calling for a “daylight recce [reconnaissance]” before any decision to retaliate, as well as Sharp’s agreement with Herrick’s recommendation. It also falsely portrayed McNamara as having agreed with Sharp that the execute order should be delayed until confirming evidence was found.

Contrary to the assumption that LBJ used the Tonkin Gulf incident to move U.S. policy firmly onto a track for military intervention, it actually widened the differences between Johnson and his national security advisers over Vietnam policy. Within days after the episode Johnson had learned enough to be convinced that the alleged attack had not occurred and he responded by halting both the CIA-managed commando raids on the North Vietnamese coast U.S. and the U.S. naval patrols near the coast.

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara standing at a podium in front of a map of Vietnam during a press conference: photo by Marion J. Trikosko, 29 June 1966 (U. S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress)

In fact, McNamara’s deception on Aug. 4 was just one of 12 distinct episodes in which top U.S. national security officials attempted to press a reluctant LBJ to begin a bombing campaign against North Vietnam.

In September 1964, McNamara and other top officials tried to get LBJ to approve a deliberately provocative policy of naval patrols running much closer to the North Vietnamese coast and at the same time as the commando raids. They hoped for another incident that would justify a bombing program. But Johnson insisted that the naval patrols stay at least 20 miles away from the coast and stopped the commando operations.

Six weeks after the Tonkin Gulf bombing, on Sept. 18, 1964, McNamara and Secretary of State Dean Rusk claimed yet another North Vietnamese attack on a U.S. destroyer in the Gulf and tried to get LBJ to approve another retaliatory strike. But a skeptical LBJ told McNamara, “You just came in a few weeks ago and said they’re launching an attack on us –- they’re firing at us, and we got through with the firing and concluded maybe they hadn’t fired at all.”

After LBJ was elected in November 1964, he continued to resist a unanimous formal policy recommendation of his advisers that he should begin the systematic bombing of North Vietnam. He stubbornly argued for three more months that there was no point in bombing the North as long as the South was divided and unstable.

Johnson also refused to oppose the demoralized South Vietnamese government negotiating a neutralist agreement with the Communists, much to his advisers’ chagrin. McGeorge Bundy later recalled in an oral history interview that he concluded that Johnson was “coming to a decision … to lose” in South Vietnam.

LBJ only capitulated to the pressure from his advisers after McNamara and Bundy wrote a joint letter to him in late January 1965 making it clear that responsibility for U.S. “humiliation” in South Vietnam would rest squarely on his shoulders if he continued his policy of “passivity.” Fearing, with good reason, that his own top national security advisers would turn on him and blame him for the loss of South Vietnam, LBJ eventually began the bombing of North Vietnam.

He was then sucked into the maelstrom of the Vietnam War, which he defended publicly and privately, leading to the logical but mistaken conclusion that he had been the main force behind the push for war all along.

The deeper lesson of the Tonkin Gulf episode is how a group of senior national security officials can seek determinedly through hardball -- and even illicit -– tactics to advance a war agenda, even knowing that the President of the United States is resisting it.

Gareth Porter, an investigative historian and journalist specialising in U.S. national security policy, received the UK-based Gellhorn Prize for journalism for 2011 for articles on the U.S. war in Afghanistan. He is the author of Manufactured Crisis: the Untold Story of the Iran Nuclear Scare.

Dean Rusk, Lyndon B. Johnson and Robert McNamara in Cabinet Room meeting, February 1968: photo by Yoichi Okamoto, February 1968 (White House Press Office / US National Archives)

On July 19, 1968, President Lyndon Johnson, right, met with President Nguyen Van Thieu of South Vietnam in Hawaii. Although most Americans still supported the idea of a non-Communist Vietnam, many had begun to withdraw their support of direct military involvement, especially following the Tet Offensive earlier that year: photo by White House Press Office, 19 July 1968 (US National Archives)

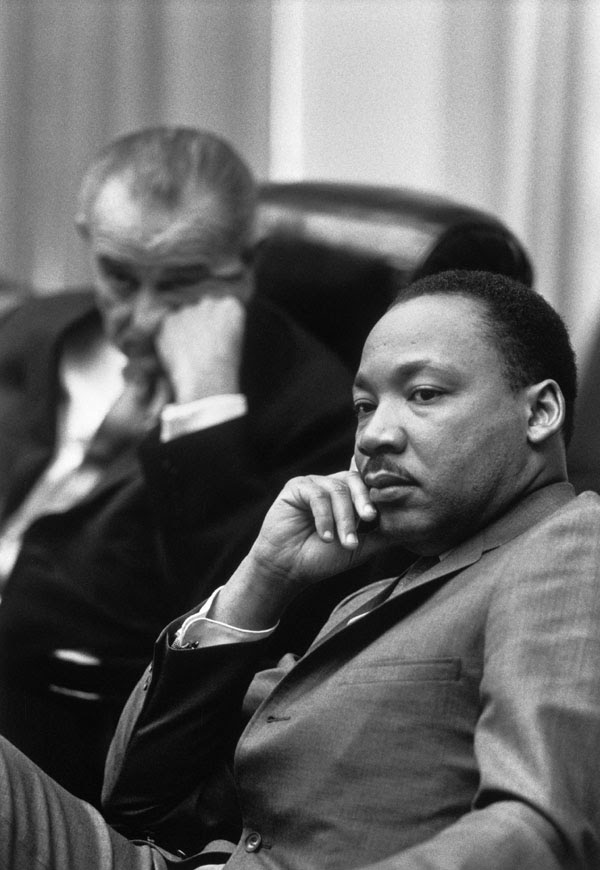

Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.; President Lyndon Johnson in background, Washington, D.C.: photo by Yoichi Okamoto, 18 March 1966 (Lyndon Baines Johnson Library / National Archives and Records Administration)

Situation Room: Walt Rostow shows President Lyndon B. Johnson a model of the Khe Sanh area: photographer unknown, 15 February 1968; image by Soerfm, 5 February 2013 (U.S. Department of Defense)

Khe Sanh under siege: photographer unknown, 1968; image by kaloaloha, 25 March 2008

Khe Sanh, 1968. An American C-123 cargo plane burns after being hit by communist

mortars while taxiing on the Marine post at Khe Sanh: photo by Peter Arnett / AP, 1 March 1968; image by mannhai, 3 November 2010

Khe Sanh, March 1968. U.S. Air Force bombs create a curtain of flying shrapnel and debris

barely 200 feet beyond the perimeter of South Vietnamese ranger

positions defending Khe Sanh during the siege of the U.S. Marine base,

March 1968. The photographer, a South Vietnamese officer, was badly

injured when bombs fell even closer on a subsequent pass by U.S.

planes: photo by AP/ARVN, Major Nguyen Ngoc Hanh, March 1968; image by Tan Hiep, 3 November 2010

U.S. sniper team at Khe Sanh, 1968: photo by David Douglas Duncan, in Jack Shulimson, Leonard A Balisol, Charles R. Smith, and David A. Dawson: US Marines in Vietnam: The Defining Year, 1968; Image by RM Gillespie, 18 November 2006; edit by Quibik, 13 September 2009 (US Marine Corps)

BBQ at Khe Sanh: photo by CBMU 301, March 1968 (U.S. Navy Seabee Museum)

Khe

Sanh post office, during the 77-day NVA siege of the U.S. Marine base:

photo by Dana Stone (1939-?1971), February 1968; image byfredleobrown, 13 January 2008

The final evacuation of Khe Sanh base complex: photographer unknown, 1 July 1968; image by HanLing 7 February 2013

Bob Hope, Danang, December 1967. Bob Hope on his way to a Christmas show in Vietnam: photo by Dana Stone (1939-?1971), December 1967; image by fredleobrown, 13 January 2008

Wounded servicemen arriving from Vietnam at Andrews Air Force Base: photo by Warren K. Leffler, 8 March 1968 (U. S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress)

8 comments:

McNamara’s deceit plunged us into a needless war. But a similar deception occurred near the end of WWII, when Harry Truman’s military advisors kept from him the information that the Japanese government, through diplomatic back channels, had been suing for peace; months of fire-bombing Japanese cities by US air forces had all but reduced the country to ashes. But militarists in the Pentagon did not want peace . . . yet. They had atomic bombs to test against Japanese civilians, several hundred thousand of whom had to die as revenge for Pearl Harbor. The new super-weapons also served to warn the Soviets of what they faced, should they get territorial in the post war world. We know how that turned out.

Hazen,

Yes, that same deception became plain once again when I was going over the records in preparing last week's Hiroshima post.

My sense of the two situations would be that for the military advisers Truman would have been a somewhat softer touch than LBJ, but definitely in both cases the President in question was strongly affected by the implicit suggestion that failure to use available weaponry could have negative political consequences; Truman was even said by some to be fearing impeachment in the event he didn't use the Bomb, which after all (and as a merchandise man this would have been a strong factor for him) had cost $2 billion to manufacture.

But I feel that at heart Truman was perfectly happy to use any and every weapon without compunction or scruple.

Whereas it seems that from the first the programmatic bombing of the North was a hard sell for the military advisers who were constantly pushing LBJ to get underway with it.

But their persistent efforts to manufacture a useful pretext eventually outlasted and overcame his resistance; and he was then left to carry out a disastrous policy which remains an embarrassment for this nation, and also effectively destroyed the reputation of the one President in our history who actually made significant progress in the area of civil rights.

You'll recall that when LBJ was VP, Kennedy (the guy who'd got us into the Vietnam quagmire in the first place) was always trying to find harmless projects for him that would keep him out of the picture; and that when the project LBJ wanted to run with turned out to be civil rights, Kennedy was not exactly thrilled.

The issue of course is the increasing access to and control of national policy by the armies of spooks whose orchestration of history from behind the scenes is now more or less taken for granted -- and extremely dangerous at that.

Because the war interests always have the one abiding goal and aim, their great joy and for them source of all meaning and value -- the perpetuation of endless global war.

Reading the transcripts of the conversations between McNamara, who had his mind set on just the one thing -- getting the bombing going -- and Johnson, who was always a bit distracted anyway (his mind was on Mississippi not the Tonkin Gulf), is like watching a slow motion film of a python having lunch.

Once the fictional "incident" had been put across, all that remained were the attendant logistical problems of picking the most precious targets, and formulating the strategy for deceiving the press and the domestic audience.

A couple of bits from the transcripts, picking up from the point when the chimera "evidence" had been reshaped as truth, and sold to the President as such by the Defense Secretary who knew very well that it was all b.s...

__

Secretary McNamara: Mr. President, we had, just had a report from the commander of that task force out there that they have sighted two unidentified vessels, uh, and three unidentified prop aircraft; and therefore the, uh, carrier launched, uh, two F-8s, two A-4Ds and four A-is, which are prop

President Johnson: Go back over those again. What, what did we launch?

Secretary McNamara: We launched two F-8 fighter aircraft, two A- which are jet attack aircraft, and four A-1Hs, which are prop-driven aircraft. So we have launched eight aircraft from the carrier to, uh, uh, examine what's in the vicinity of the destroyers and to protect the destroyers. The report is that they have observed, and we don't know by what means, whether this is radar or otherwise -- I suspect it's radar-- two unidentified vessels and three unidentified prop aircraft in the vicinity of the destroyers.

President Johnson: What else do we have out there?

Secretary McNamara: We have the, only the Ticonderoga, with its aircraft, uh, and a protective destroyer screen. I think there are three destroyers with the Ticonderoga. We have the Constellation [an aircraft carrier], which is moving out of Hong Kong, and which I uh sent orders to about an hour or two ago to move down towards South Vietnam. We don't know exactly how long it'll take; we guess about 30 hours. We have ample forces to respond not only to these attacks on the destroyers but also to retaliate should you wish to do so against targets on the land. And when I come over at noontime, I'll bring you a list of alternative target systems. We can mine the Swatow [a type of North Vietnamese patrol vessel] bases, we can-and I just issued ordered to Subic Bay and the Philippines to fly the mines out to the carrier, so we'll be prepared to do it if you want to do it. We can destroy the Swatow craft by bombing. There Is a petroleum system that is concentrated, uh, uh,

Very faint whisper: seventy-two

Secretary McNamara: Seventy percent of the petroleum supply of North Vietnam we believe is concentrated in three, uh, dumps, and we can bomb those, bomb or strafe those dumps and destroy the petroleum system, which would be the petroleum for the patrol craft. In addition, there are certain prestige targets that we've been working on the last several months, and we have target folders prepared on those. For example, there is one bridge that is the key bridge on the rail line south out of, uh, out of Hanoi, and we could destroy that. And there are other prestige targets of that kind.

President Johnson: All right. Uh, good.

__

[continues:]

Secretary Robert McNamara: Mr. President, we just had word by telephone from Admiral Sharp that the destroyer is under torpedo attack.

Secretary McNamara: I think I might get, uh, Dean Rusk and Mac Bundy and have 'em come over here and we'll go over these retaliatory actions. And then we ought to

President Johnson: I sure think you ought to agree with that, yeah.

Secretary McNamara: And I've got a category here. I'll call the two of them.

President Johnson: Now where are these torpedoes coming from?

Secretary McNamara: Well, we don't know. Presumably from these unidentified craft that I mentioned to you a moment ago. We thought that the unidentified craft might include one, uh, one PT boat, which has torpedo capability and two Swatow boats which we don't credit with torpedo capability, although they may have it.

President Johnson: What are these planes of ours doing around while they're being attacked?

Secretary McNamara: Well, presumably, the planes are attacking the, the ships. We don't have any, uh, word from, from Sharp on that. The planes would be in the area at the present time. All, all eight of them.

President Johnson: OK.

One aspect of this story that is a factor in the historical assessment is the element of retrospective reconstruction and reputation-repair successfully managed by the very shrewd McNamara in later years (with LBJ of course well out of the way by then) -- in particular the Errol Morris film The Fog of War, in which Morris helps out crucially with the laundering job.

McNamara is, by the time the film was made, quite aware that some bits of the truth have got out over the years. By this time the NSA had already been forced to come up with their own whitewash; cooperatively enough, most historians of the war continued to call the Gulf deception a "misunderstanding," giving the benefit of the doubt to the original deliberate falsification.

__

from The Fog of War, transcript:

August 2, 1964

On August 2nd, the destroyer Maddox reported it was attacked by a North Vietnamese patrol boat. It was an act of aggression against us. We were in international waters. I sent officials from the Defense Department out and we recovered pieces of North Vietnamese shells ? that were clearly identified as North Vietnamese shells — from the deck of the Maddox. So there was no question in my mind that it had occurred. But, in any event, we didn't respond.

And it was very difficult. It was difficult for the President. There were very, very senior people, in uniform and out, who said "My God, this President is" ? they didn't use the word 'coward,' but in effect ? "He's not protecting the national interest."

August 4, 1964

Two days later, the Maddox and the Turner Joy, two destroyers reported they were attacked.

Johnson: Now, where are these torpedoes coming from?

McNamara: Well, we don't know, presumably from these unidentified craft.

There were sonar soundings, torpedoes had been detected — other indications of attack from patrol boats. We spent about ten hours that day trying to find out what in the hell had happened. At one point, the commander of the ship said, "We're not certain of the attack." At another point they said, "Yes, we're absolutely positive." And then finally late in the day, Admiral Sharp said, "Yes, we're certain it happened."

So I reported this to Johnson, and as a result there were bombing attacks on targets in North Vietnam. Johnson said we may have to escalate, and I'm not going to do it without Congressional authority. And he put forward a resolution, the language of which gave complete authority to the President to take the nation to war: The Tonkin Gulf Resolution.

Now let me go back to the August 4th attack.

August 4. 12:22 PM

Admiral Sharp: Apparently, there have been at least nine torpedoes in the water. All missed.

General Burchinal: Yup.

Admiral Sharp: Wait a minute now. I'm not so sure about this number of engaged. We've got to check it out here.

97 Minutes Later.

Admiral Sharp: He [Admiral Moore] said many of the reported contacts with torpedoes fired appear doubtful. Freak weather effects on radar and overeager sonar men may have accounted for many reports.

General Burchinal: Okay, well I'll tell Mr. McNamara this.

Admiral Sharp: That's the best I can give you Dave, sorry.

9 Minutes Later.

Admiral Sharp: It does appear now that a lot of these torpedo attacks were from the sonar men, you see. And, they get keyed up with a thing like this and everything they hear on the sonar is a torpedo.

General Burchinal: You're pretty sure there was a torpedo attack, though?

Admiral Sharp: Oh, no doubt about that?I think. No doubt about that.

McNamara: It was just confusion, and events afterwards showed that our judgment that we'd been attacked that day was wrong. It didn't happen. And the judgment that we'd been attacked on August 2nd was right. We had been, although that was disputed at the time. So we were right once and wrong once.

(And that's a whole lot of wrong, Bob, and an awfully generous stretching of the word "we" -- what is really meant, of course, is "we of the shadow government...")

I've always felt a little sorry for LBJ. McNamara always struck me as a psycopath.

I long for the day when the Kennedy myth is finally exploded.

One of those Berkeley think-tank "geniuses" (self designated), let loose on the real world, our Bob... a willing servant of incremental doom.

He led LBJ out on a limb much as a blind man, let him take the fall, then held out long enough to have himself "restored" (as a "feeling", "caring" human being, with a "conscience" & c. & c.) by the helpful documentarist / stooge Morris.

The defeat of Johnson was affecting to behold. The cities were going up in flames after the death of Dr King. The centre was not holding. LBJ went on national tv to give a speech that was expected to be about the war. Congress had declared that he would be eligible for an additional term. The consummate old time politician -- there had been no inkling he was not going to be able to stay the course. But during the speech his face seemed to be undergoing changes, involuntary tics, the several medications kicking in and out. The face of a man who knows he's gone too far down the wrong road and can make himself go no further.

He stepped away, declared he would not run again. And one could then see he had been broken by the job that had fallen upon him. He would be dead of a heart attack at 64.

This long war he inherited and tried to carry on ruined his memory. It changed this country forever, and not for the better.

The morning after LBJ gave that speech, we took off on a cross country junket interrupted by a massive car crash on the freeway in Ohio, in which what few belongings we possessed were scattered over a mile of hard American asphalt.

The trip was one long aggravating circumstance. In Colorado Springs there was a vast crush of uniformed military personnel at the airport, terrified young recent draftees waiting for the plane out to Nam, every one of them with the look of a terrified rabbit.

And for good reason.

Post a Comment