Never has the hour been more desperate in #Yarmouk: image via Raquel Marti @raquel_unrwace, 7 April 2015

In regard to what's happening in #Yarmouk, I think this photo is very relevant right now. We stand together.: image via MohaNNad Rachid @TheMoeDee, 5 April 2015

A scar on humanity. #Yarmouk: image via F. @Palestinianism, 6 April 2015

Palestinian kids died of hunger. Did they not deserve humanity? Crisis In #Yarmouk: image via Said Shoaib @saidshouib, 5 April 2015

#Yarmouk camp is dying 18,000 Palestine refugees are trapped No #Light & food or warmth @GazaReports @Palaestina: image via Hacker Brigade @HackerBrigades, 5 April 2015

#Yarmouk camp is dying 18,000 Palestine refugees are trapped No #Light & food or warmth @GazaReports @Palaestina: image via Hacker Brigade @HackerBrigades, 5 April 2015

The desperate situation in #Yarmouk refugee camp is a scar on humanity. The world must act to end this tragedy: image via Jack Moore @JXFM, 5 April 2014

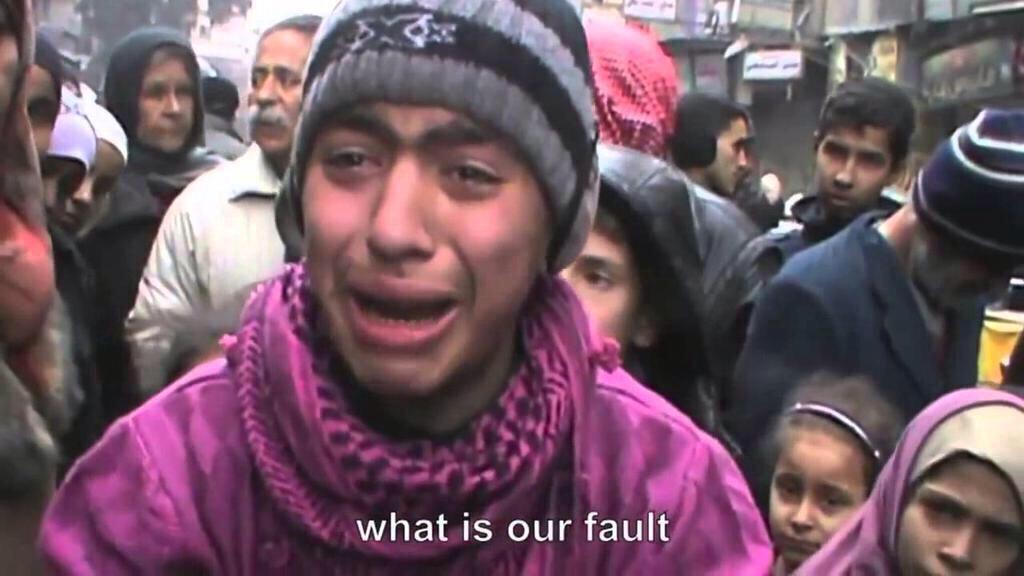

What happened to the world!! Did they forget that there are humans in #Yarmouk!! What are they busy with?? #Syria [photo by Rami El-Sayed for AFP]: image via Hacker Brigade @HackerBrigades, 5 April 2015

The desperate situation in #Yarmouk refugee camp is a scar on humanity. The world must act to end this tragedy: image via Jack Moore @JXFM, 5 April 2014

UNSG urges ‘concerted action to save lives, restore measure of humanity’ in besieged #Yarmouk: image via UN News Centre @UN_ News_Centre, 9 April 2015

Must be said, these are guardians of #Yarmouk. The volunteers and workers in the Palestinian Red Crescent. V. Jafra.: image via Dima S. @YasminWaQahwa, 5 April 2015

Coalition what are you doing for #Yarmouk? @BarackObama @fhollande @DavidCameron @UN: image via la skala @fantasia195, 5 April 2015

How much more can #Palestinians suffer? #Yarmouk Refugee Camp attacked by ISIS Inhumane: UN: image via Angi Mansi @WorkPsychol, 6 April 2015

Assad dropping bombs from the air while ISIS slaughters on the ground #Yarmouk: image via Global Revolution TV @GlobalRevLive, 5 April 2015

What happened to the world!! Did they forget that there are humans in #Yarmouk!! What are they busy with?? #Syria: image via Hacker Brigade @HackerBrigades, 5 April 2015

Good morning from #Yarmouk Camp [photo by AFP]: image via Leith Al-Halabi @leithfadel, 9 April 2015

‘I Am Not a Statistic’

‘The Three Kings’: three brothers waiting their turn to leave the besieged Yarmouk Palestine refugee camp near Damascus in order to receive medical treatment: photo by Niraz Saied via UNRWA, 29 November 2014

Yarmouk youth wins 2014 UNRWA/EU photography competition: UNRWA, Gaza, 26 November 2014

A timeless photograph capturing the anguish of children affected by

the ongoing conflict in Syria has won first prize in the European

Union-supported 2014 UNRWA youth photography competition.

The theme for the 2014 competition, ‘I Am Not a Statistic’, called on participants to capture the stories and emotions of the people behind news headlines, making personal the lists of Palestinians killed, wounded and displaced by conflicts throughout the region.

The annual competition is open to all Palestine refugees aged 16-29.

The winning photograph was captured by Niraz Saied, age 23, in Yarmouk Palestine refugee camp, near Damascus in Syria. Titled ‘The Three Kings’, the image shows three brothers waiting their turn to leave the besieged refugee camp in order to receive medical treatment.

Speaking about his photography, Mr. Saied said: “You can’t find a complete family in the refugee camp. I used to feel that in every portrait of a Palestinian family you could see the shadow of a person missing, and that is why my photos are dimly lit.

“But there is always hope. Difficult times have fallen on Yarmouk camp before and they have always passed. The Palestinians continue to struggle to live. The Palestinian people appreciate life and deserve life. Despite all that they live through, they hope that tomorrow will be a better day.”

'the children of Yarmouk were created as heroes'

The theme for the 2014 competition, ‘I Am Not a Statistic’, called on participants to capture the stories and emotions of the people behind news headlines, making personal the lists of Palestinians killed, wounded and displaced by conflicts throughout the region.

The annual competition is open to all Palestine refugees aged 16-29.

The winning photograph was captured by Niraz Saied, age 23, in Yarmouk Palestine refugee camp, near Damascus in Syria. Titled ‘The Three Kings’, the image shows three brothers waiting their turn to leave the besieged refugee camp in order to receive medical treatment.

Speaking about his photography, Mr. Saied said: “You can’t find a complete family in the refugee camp. I used to feel that in every portrait of a Palestinian family you could see the shadow of a person missing, and that is why my photos are dimly lit.

“But there is always hope. Difficult times have fallen on Yarmouk camp before and they have always passed. The Palestinians continue to struggle to live. The Palestinian people appreciate life and deserve life. Despite all that they live through, they hope that tomorrow will be a better day.”

'the children of Yarmouk were created as heroes'

The desperate situation in #Yarmouk refugee camp is a scar on humanity. The world must act to end this tragedy [photo by Niraz Saied]: image via Jack Moore @JXFM, 5 April 2014

Palestinian youth brave Yarmouk siege with humour; Young

Palestinians, at risk of being overrun by Islamic State and under

government siege since 2012, give 'weight-loss' advice in new video: Mamoon Alabassi, Middle East Eye, 7 April 2015

A video reportedly from inside the Yarmouk refugee camp in

Damascus shows Palestinian youths trying to brave the miserable

conditions caused by a prolonged government siege and a recent

infiltration by Islamic State (IS) militants, who are now controlling

much of the camp.

The recording, which is not independently verified, appears to be recent, with the participants mentioning the militants' entrance into the camp.

IS militants took control of 90 percent of the camp -- which was established in the 1950s to house Palestinian refugees -- last week, although they have since lost some ground.

The area had previously been under siege by the government of embattled Syrian President Bashar al-Assad since December 2012, and was said to be "on the brink of starvation" because of a blockade preventing food and goods from entering.

The video begins with two young men talking to the camera, with one of them saying: "I hope you won't think this video will be showing people and children [starving to death], as is shown on [the Gaza-based] al-Quds satellite TV channel."

"No, we are in the Yarmouk camp, the camp of plentifulness," he added. "Take a look at the floor," said the man as the camera shows water in the street. "This is not water. This is an excess of cooking [flooding the streets]."

The youth then moved on to mockingly give his viewers advice on how to lose weight.

"Would you like to lose weight? Green tea won't work, nor will ginger … just come to Yarmouk camp for five months, in each month you'll lose 9kg," he said, adding the Arabic proverb: "Ask someone with experience instead of asking a doctor."

The youth passed by a damaged mosque, which one of them pointed to saying: "Here's Palestine Mosque … hope you don't think that it was ever shelled. No, never."

One of the youth then said, apparently quoting someone: "All the children of the world were created as children, except the children of Yarmouk were created as heroes."

"God damn the person who came up with that quote ... why did we have to become heroes and stay in the camp?" one asked. The second replied: "We should have migrated ... to areas that have food … but they told us that the rent was high."

Men walk past destroyed buildings in the Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp in the Syrian capital Damascus on 6 April: photo by AFP via Middle East Eye, 7 April 2015

On the rising food prices, one noted that the price of "rice outside (Yarmouk camp) is 120 [Syrian Dinars], while here it is 10,000 [Syrian Dinars]. But we are happy here … look at the peaceful people … singing and dancing."

The two men then passed by a shop, and directed the camera to its owner.

"The guy's prices were high even before the crisis," one said, before approaching the smiling shop owner to say hello.

Despite the cheerful mood that they are trying to put up, it is clear from the footage how dire their surroundings are. They pointed to a cyclist, saying that his bike actually works on petrol.

"We ask the troublesome channels that claim Yarmouk camp is under siege to stop reporting that. It is 'absolutely' [said in English] not true," one said.

"It's true that my grandmother died of hunger but not because the camp was under siege but because my grandfather was so stingy - he never allowed her near the fridge," he added.

The two, with a number of others, were heading towards the flat of someone named Mr Ayham, where they are all invited for lunch.

"We are invited to Mr Ayham's place. He has linked his satellite dish to the bin downstairs so that he can view dirty channels," one of the youths in the video said.

Then they gather in a room and sing together joyfully, as one holds the guitar. After a short while a small tray is shown holding tiny portions of food, to which they sing: "This is the reward of the steadfast people who have sacrificed their lives."

Then at end of the video, one of the youth told a timely joke. "A cardboard box went to meet another cardboard box; it discovered that it was empty."

The recording, which is not independently verified, appears to be recent, with the participants mentioning the militants' entrance into the camp.

IS militants took control of 90 percent of the camp -- which was established in the 1950s to house Palestinian refugees -- last week, although they have since lost some ground.

The area had previously been under siege by the government of embattled Syrian President Bashar al-Assad since December 2012, and was said to be "on the brink of starvation" because of a blockade preventing food and goods from entering.

The video begins with two young men talking to the camera, with one of them saying: "I hope you won't think this video will be showing people and children [starving to death], as is shown on [the Gaza-based] al-Quds satellite TV channel."

"No, we are in the Yarmouk camp, the camp of plentifulness," he added. "Take a look at the floor," said the man as the camera shows water in the street. "This is not water. This is an excess of cooking [flooding the streets]."

The youth then moved on to mockingly give his viewers advice on how to lose weight.

"Would you like to lose weight? Green tea won't work, nor will ginger … just come to Yarmouk camp for five months, in each month you'll lose 9kg," he said, adding the Arabic proverb: "Ask someone with experience instead of asking a doctor."

The youth passed by a damaged mosque, which one of them pointed to saying: "Here's Palestine Mosque … hope you don't think that it was ever shelled. No, never."

One of the youth then said, apparently quoting someone: "All the children of the world were created as children, except the children of Yarmouk were created as heroes."

"God damn the person who came up with that quote ... why did we have to become heroes and stay in the camp?" one asked. The second replied: "We should have migrated ... to areas that have food … but they told us that the rent was high."

Men walk past destroyed buildings in the Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp in the Syrian capital Damascus on 6 April: photo by AFP via Middle East Eye, 7 April 2015

On the rising food prices, one noted that the price of "rice outside (Yarmouk camp) is 120 [Syrian Dinars], while here it is 10,000 [Syrian Dinars]. But we are happy here … look at the peaceful people … singing and dancing."

The two men then passed by a shop, and directed the camera to its owner.

"The guy's prices were high even before the crisis," one said, before approaching the smiling shop owner to say hello.

Despite the cheerful mood that they are trying to put up, it is clear from the footage how dire their surroundings are. They pointed to a cyclist, saying that his bike actually works on petrol.

"We ask the troublesome channels that claim Yarmouk camp is under siege to stop reporting that. It is 'absolutely' [said in English] not true," one said.

"It's true that my grandmother died of hunger but not because the camp was under siege but because my grandfather was so stingy - he never allowed her near the fridge," he added.

The two, with a number of others, were heading towards the flat of someone named Mr Ayham, where they are all invited for lunch.

"We are invited to Mr Ayham's place. He has linked his satellite dish to the bin downstairs so that he can view dirty channels," one of the youths in the video said.

Then they gather in a room and sing together joyfully, as one holds the guitar. After a short while a small tray is shown holding tiny portions of food, to which they sing: "This is the reward of the steadfast people who have sacrificed their lives."

Then at end of the video, one of the youth told a timely joke. "A cardboard box went to meet another cardboard box; it discovered that it was empty."

By now, the people trapped in #Yarmouk will have no food #SaveYarmouk: image via UNRWA @UNRWA, 8 April 2015

"a culmination of the story of almost each and every Palestinian"

The

United Nations Relief and Works Agency distributes food aid to

Palestinians in Yarmouk refugee camp near Damascus, Syria. Yarmouk camp

is home to thousands of Palestinian refugees who are barred by Israel

from returning to their lands: photo by UNRWA vis Middle East Eye, 9 April 2015

Yarmouk: Horrific impasse or momentous turning point?: Ghaada Ageel, Middle East Eye, 9 April 2015

The story of the tens of thousands starving and under attack

today in the Yarmouk refugee camp near Damascus is a culmination of the

story of almost each and every Palestinian. It is the story of my

90-year-old grandmother who continues to live the misery of Khan Younis

refugee camp in the Gaza Strip. It is the story of my cousins in Yemen

caught in the current attack. It is the story of my sister in Syria

forced to flee for her life three years ago with her children and it is

the story of my aunts and uncles in Saudi Arabia and United Arab

Emirates whose lives and futures hang in the balance awaiting a piece of

official paper. It is the story of my neighbours, relocated to Libya

who now live in limbo with no place to go. Yarmouk camp is the

culmination to the story of successive generations of Palestinian people

born into lives of exile with suspended presents and futures.

This story, then, is not “simply” one of the profound suffering of a

group of defenceless civilians trapped in a war zone. It extends far

beyond the de-contextualised renderings of mainstream media,

spotlighting refugees in dire circumstances, facing death and

starvation. It includes but also considerably predates reports

of “residents including infants and children … subsisting for long

periods on diets of stale vegetables, herbs, powdered tomato paste,

animal feed and cooking spices dissolved in water”.

The

story of Yarmouk began almost seven decades ago when some

three-quarters-of-a-million Palestinians were forcibly displaced from

Mandatory Palestine in 1948, then subjected to continuing, multiple

displacements both across and beyond the Middle East. Among too many

instances to list here, these include: 400,000 Palestinians (many of

them refugees from 1948) displaced by Israel in 1967, over 300,000

fleeing Kuwait in the early nineties during and after the first Gulf

war, tens of

thousands expelled by the Libyan regime and housed in makeshift camps at

the Egyptian Libyan borders in 1995 and 22,000 fleeing Iraq during and

after the American led invasion in 2003.

Founded in 1957 just south of Damascus, the Yarmouk camp became home

to many thousands of refugees, most of whom originated in the northern

part of Mandatory Palestine, in Safad, Haifa, and Jaffa. Expelled from

their homes in 1948, these Palestinian refugees have been barred ever

since from returning to their lands.

Prior to the 2011 outbreak of the Syrian civil uprising the

population of Palestinian refugees in Yarmouk numbered over 150,000.

With the uprising now turned, through imperialist intervention, into

several larger proxy wars,

continued warfare has already displaced ninety percent of the camp

residents, who fled elsewhere in Syria or to the neighbouring countries

of Jordan, Turkey and Lebanon. For those who have been unable to flee,

including some 3,500 children,

the current situation is appalling. Since fighting intensified early

this month, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine

Refugees (UNRWA) has been unable to deliver much needed necessities.

UNRWA spokesman Christopher Gunness

has said: “That means that there is no food, there is no water and

there is very little medicine… The situation in the camp is beyond

inhumane.”

Yarmouk, the individual and the collective story, is about millions

of Palestinian refugees currently scattered across the Arab world,

struggling to make lives and livelihoods and repeatedly forced to move

into the unknown. It is, no less, about the Palestinians living under

Israel’s control in the occupied territories, inside Israel and all over

the globe, with and without relatives in the Syrian camp, who are

forced to look on helplessly at the unbearable spectacle of slow

starvation playing out upon their families, friends and people.

Yarmouk is the story of an entire nation consistently denied access

to its most basic human rights. It is about generation after generation

of Palestinians whose lives of uncertainty, humiliation and poverty

result directly from a consistent UN failure to fulfill the obligation

it undertook in resolution number 194,

that is, that Palestinian “refugees wishing to return to their homes

and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at

the earliest practicable date”. This failure has persisted for 67 years

now, despite the fact that Israel’s very admissibility into the United

Nations was linked with the measure for allowing Palestinian refugees to

return to their lands.

Israel too, then, bears a direct and distinct responsibility for the

fact that Palestinian refugees are dying today in Syria. The refugees

living, and now dying, in Yarmouk camp and all those living, and often

subsisting, in 59 other camps in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the West Bank and Gaza are where they are

because Israel has, for all these years, consistently blocked their

return. The state of Israel continues to defy UN resolutions,

international law and conventional norms of human rights, all of which

would allow Palestinians to exercise their right of return.

This being the case, Yarmouk is clearly also a story of an immoral

world leadership that allowed millions of people to be exiled from world

memory and to drop off its radar screens, allowing time and

powerlessness to eradicate their rights and dreams. It is, as well, the

story of a supposedly “developed” world that is utterly impotent,

ineffective, helpless and indifferent, which, yet again, stands by --

watching, knowing, yet doing nothing, offering no options to Yarmouk;

whether to its predominantly Palestinian residents or to the many

indigenous Syrians trapped there as well.

There is no doubt that the Islamic State, the Assad government, as

well as additional armed groups currently fighting for control in

Yarmouk, are part of the complex picture of today’s Syria. Each and all

of them bear direct responsibility for the misery forced upon the people

of Yarmouk. It would be foolish to ignore this. But the broader, highly

pertinent context seems to be totally absent from most media reports.

The Palestinian refugees of Yarmouk, and many more elsewhere are

subject to whatever they are facing because Israel has denied their

inalienable rights while the UN and the international community have

allowed and enabled Israel’s denial. A genuine will and a just world

public could save the Palestinians of Yarmouk, recognising and enacting

the right of return of these refugees. This single act could prove

deeply transformational, bringing hope and unaccustomed, careful trust

to the region.

Yarmouk, then, is poised to become either the story of a prolonged,

familiar impasse, exacting an horrific price in human lives, or the

story of a momentous turning point.

Ghada Ageel is a visiting professor at the

University of Alberta Political Science Department (Edmonton, Canada),

an independent scholar, and active in the Faculty4Palestine-Alberta. Her

new book “Apartheid in Palestine: Hard Laws and harder experiences” is

forthcoming with the University of Alberta Press - Canada

My missing family

UN renews call for end to fighting in #Yarmouk, urges opening of humanitarian corridor.: image via UN News Centre @UNNewsCentre, 5 April 2015

My missing family in Syria: Naming and shaming in Yarmouk: Ramzy Baroud, Middle East Eye, 10 April 2015

We

must remember that there are still 18,000 people trapped in Yarmouk,

and even if it is untimely, we must do something -- anything

Members of my family in Syria’s Yarmouk went missing many months

ago. We haven’t an idea who is dead and who is alive. Unlike my other

uncle and his children in Libya, who fled the NATO war and turned up

alive but hiding in some desert a few months later, my uncle’s family in

Syria disappeared completely as if ingested by a black hole, to a whole

different dimension.

I chose the “black hole” analogy, as opposed to the one used by UN

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon -- "the deepest circle of hell" -- which he

recently uttered in reference to the plight of Palestinians in Yarmouk

following the advances made by the notorious Islamic State (IS) militias

in early April. If there is any justice in the hereafter, no

Palestinian refugee -- even those who failed to pray five times a day or

go to church every Sunday -- deserves to be in any “circle of hell”, deep

or shallow. The suffering they have endured in this world since the

founding of Israel atop their towns and villages in Palestine some 66

years ago is enough to redeem their collective sins, past and present.

For now, however, justice remains elusive. The refugees of Yarmouk -- whose population once exceeded 250,000,

dwindling throughout the Syrian civil war to 18,000 -- is a microcosm of

the story of a whole nation, whose perpetual pain shames us all, none

excluded.

Palestinian refugees (some displaced several times) who escaped the

Syrian war to Lebanon, Jordan or are displaced in Syria itself, are

experiencing the cruel reality under the harsh and inhospitable terrains

of war and Arab regimes. Many of those who remained in Yarmouk were

torn to shreds by the barrel bombs of the Syrian army, or victimised –-

and now beheaded -- by the malicious, violent groupings that control the

camp, including the al-Nusra Front, and as of late, IS.

Those who have somehow managed to escape bodily injury are starving. The starvation in Yarmouk

is also the responsibility of all parties involved, and the “inhumane

conditions” under which they subsist – especially since December 2012 –

is a badge of shame on the forehead of the international community in

general, and the Arab League in particular.

These are some of the culprits in the suffering of Yarmouk:

Israel

Israel bears direct responsibility in the plight of the refugees in

Yarmouk, as they do the five million other refugees across the Middle

East. The refugees of Yarmouk are mostly the descendants of Palestinian

refugees from historic Palestine, especially the northern towns,

including Safad, which is now inside Israel. The camp was established in

1957, nearly a decade after the Nakba –- the “Catastrophe” of 1948,

which saw the expulsion of nearly a million refugees from Palestine. It

was meant to be a temporary shelter, but it became a permanent home. Its

residents never abandoned their right of return to Palestine, a right enshrined in UN resolution 194.

Israel knows that the memory of the refugees is its greatest enemy,

so when the Palestinian leadership requested that Israel allow the

Yarmouk refugees to move to the West Bank, Israeli Prime Minister

Benjamin Netanyahu had a condition:

that they renounce their right of return. Palestinians refused. The

refugees would have refused. History has shown that Palestinians would

endure untold suffering and not abandon their rights in Palestine. The

fact that Netanyahu would place such a condition is not just a testimony

to Israel’s fear of Palestinian memory, but the political opportunism

and sheer ruthlessness of the Israeli government.

2000 Yarmouk residents have been evacuated from the camp since Friday #Syria #Yarmouk: image via Middle East Eye @MiddleEastEye, 5 April 2015

The Palestinian Authority (PA)

The PA was established in 1994 based on a clear charter where a small

group of Palestinians “returned” to the occupied territories, set up a

few institutions and siphoned billions of dollars in international aid,

in exchange for abandoning the right or return for Palestinian refugees,

and ceding any claim on real Palestinian sovereignty and nationhood.

The Palestinian nation became whatever Palestine's political elite wished it to

be. The new “Palestine” had no definable boundaries, excluded the

diaspora community and millions of refugees, saw Palestinians in Israel

as an internal Israeli matter, split the West Bank and Gaza, and had no

patience for any democratic endeavor.

Not

only had it completely abandoned the refugees, save of few passing

references, the PA left Lebanon's half-million to fend for themselves,

locked in refugee camps that were not allowed

to grow or develop, with no voice or political representation.

When the civil war in Syria began to quickly engulf the refugees, and although such a reality was to be expected, President Mahmoud Abbas’s

authority did so little as if the matter was of no importance or had no

bearing on the Palestinian people as a whole.

True, Abbas made a few

statements calling on Syrians to

spare the refugees what was essentially a Syrian struggle, but not much

more. When IS took over the camp, Abbas dispatched his labour minister,

Ahmad Majdalani to Syria. The latter made a statement that the factions

and the Syrian regime would unite against IS -- which, if true, is likely to ensure the demise of hundreds more.

If Abbas had invested 10 percent of the energy he spent in his

“government’s” media battle against Hamas or a tiny share of his

investment in the frivolous “peace process”, he could have at least

garnered the needed international attention and backing to treat the

plight of Palestinian refugees in Syria’s Yarmouk with a degree of

urgency. Instead, they were left to die alone, as the PA remained safe

in its Ramallah bubble, unhindered by the cries of orphans, widows and

bleeding men.

The Syrian regime

When rebels seized Yarmouk in December 2012, President Bashar al-Assad's forces shelled the camp without

mercy while Syrian media never ceased to speak about liberating

Jerusalem. The contradictions between words and deeds when it comes to

Palestine is an Arab syndrome that has afflicted every single Arab

government and ruler since Palestine became the “Palestine question” and

the Palestinians became the “refugee problem”.

Syria is no exception, but Assad, like his father Hafez before him,

is particularly savvy in utilising Palestine as a rallying cry aimed

solely at legitimising his regime while posing as if a revolutionary

force fighting colonialism and imperialism. Palestinians will never

forget the siege and massacre of

Tel al-Zaatar (where Palestinian refugees in Lebanon were besieged,

butchered but also starved as a result of a siege and massacre carried

out by right-wing Lebanese militias and the Syrian army in 1976), as

they will not forget or forgive what is taking place in Yarmouk today.

The Syrian army imposed a siege on Yarmouk over two years ago to

strangle the rebels. Many of the camp’s homes were turned to rubble

because of Assad’s barrel bombs, shells and airstrikes. Trapped within a

hermetic siege and infighting militias, suffering from the lack of

food, having no access to electricity or running water or medical

supplies, the refugees perished slowly and painfully. Meanwhile, Syrian

television is still hatching plans to liberate Palestine.

Many of Yarmouk's homes were turned to rubble because of Assad’s barrel bombs, shells and airstrikes: photo via Middle East Eye, 10 April 2015

The rebels

The so-called Free Syria Army (FSA) should have never entered

Yarmouk, no matter how desperate they were for an advantage in their war

against Assad. It was criminally irresponsible considering the fact

that, unlike Syrian refugees, Palestinians had nowhere to go and no one

to turn to. The FSA invited the wrath of the regime, and couldn’t even

control the camp, which fell into the hands of various militias that are

plotting and bargaining amongst each other to defeat their enemies, who

could possibly become their allies in their next pathetic street

battles for control over the camp.

The access that IS gained in Yarmouk was reportedly facilitated by the al-Nusra Front which is an enemy of

IS in all places but Yarmouk. Nusra is hoping to use IS to defeat the

mostly local resistance in the camp, arranged by Aknaf Beit al-Maqdis,

before handing the reins of the besieged camp back to the al-Qaeda

affiliated group. And while criminal gangs are politicking and

bartering, Palestinian refugees are dying in droves.

The UN and Arab League

Cries for help have been echoing from Yarmouk for years, and yet none

have been heeded. Recently, the UN Security Council decided to hold a

meeting and discuss the situation there as if the matter was not a top

priority years ago. Grandstanding and concerned press statements aside,

the UN has largely abandoned the refugees. The budget for UNRWA, which

looks after the nearly 60 Palestinian refugee camps across Palestine and

the Middle East, has shrunk so significantly, the agency often finds

itself on the verge of bankruptcy.

The UN refugee agency, better funded and equipped to deal with

crises, does little for the Palestinian refugees in Syria. Promises of

funds for UNRWA, which frankly could have done much better to raise

awareness and confront the international community over their disregard

for the refugees, are rarely met.

The Arab League are even more responsible. The League was largely

established to unite Arab efforts to respond to the crisis in Palestine,

and was supposed to be a stalwart defender of Palestinians and their

rights. But the Arabs too have disowned Palestinians as they are

intently focused on conflicts of more strategic interests -- setting up

an Arab army with clear sectarian intentions and aimed largely at settling scores.

Many of us

The Syrian conflict has introduced great polarisation within a

community that once seemed united for Palestinian rights. Those who took

the side of the Syrian regime wouldn’t concede for a moment, and the

Syrian government could have done more to lessen the suffering in the

camp. Those who are anti-Assad insist that the entire evil deed is the

doing of him and his allies.

Not only does such polarisation lead to irrational conclusions as it

selects particular pieces of evidence and ignores others. It is also

counterproductive. This useless fight reflects a disappointing fact that

many who consider themselves “pro-Palestinians” are driven by

groupthink and slogans, not human rights; self-serving ideologies, not

the well-being of the refugees; stubborn politics, not justice in its

purest forms.

Those people, too, are responsible for wasting time, confusing the

discussion and wasting energies that could have been used to create a

well-organised international campaign to raise awareness, funds and

practical mechanisms of support to help Yarmouk in particular, and

Palestinians refugees in Syria in general.

It behoves us all to take a moment to hang our heads in silence, but

also shame, over what has befallen Yarmouk, as we stood, watching,

bickering and doing nothing.

But we ought to remember that there are still 18,000 trapped in

Yarmouk and organise on their behalf so that, even if it is untimely, we

need do something. Anything.

Ramzy Baroud is an internationally-syndicated columnist, a media consultant, an

author of several books and the founder of PalestineChronicle.com. He is

currently completing his PhD studies at the University of Exeter. His

latest book is My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story

(Pluto Press, London)

UN Chief: #Syria's #Yarmouk Beginning to Resemble 'Death Camp': image via Samzyxx @semzyxx, 9 April 2015

watching a massacre unfold

Trapped civilians ‘more desperate than ever’ amid fighting in #Yarmouk, warns @UNRWA chief Beginning to Resemble 'Death Camp': image via UN News Centre @UN_ News_Centre, 6 April 2015

While the PLO refuses to be drawn into the army drive to regain

Yarmouk from militants, the United Nations continues to express concern

for the safety and protection of Syrians and Palestinians in the camp: Reuters via SBS, 10 April 2015

The PLO said on Thursday it refused to be drawn into supporting

any military offensive in the war-battered Yarmouk camp on the outskirts

of Damascus, backing away from earlier comments by one of its members

that lent support to Syrian army action against insurgents there.

The radical Islamist group Islamic State, which rules swathes of

Syria and Iraq, seized almost all of Yarmouk in recent days, brushing

aside local militia opposed to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

"We refuse to be drawn into any armed campaign, whatever its nature

or cover, and we call for resorting to other means to spare the blood of

our people and prevent more destruction and displacement for our people

of the camp," the Palestine Liberation Organisation said in a statement

issued from Ramallah.

Earlier, Ahmad Majdalani, a member of its executive committee who was

sent by the PLO leadership to Damascus to discuss the crisis with the

government, said he fully endorsed a Syrian military offensive to regain

control of the camp.

Majdalani blamed the hard-line Islamists in control of the camp of exploiting the plight of Palestinians to their own ends.

"They (radical Islamists) have tried to use the camp as a launching

pad to expand their scope of clashes and their terror activities inside

and outside the camp," said Majdalani, a former minister in the

Western-backed Palestinian Authority.

Majdalani said the Syrian army alongside local Palestinian groups had

some success in pushing back Islamic State and had so far secured 35

percent of the camp.

The sprawling Yarmouk camp was home to some 160,000 Palestinians

before the Syrian conflict began in 2011, refugees from the 1948 war of

Israel's founding, and their descendents.

Majdalani said there were just 17,500 residents left, with around 2,000 evacuated since the latest round of fighting.

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, which monitors the conflict

from Britain, earlier said that Islamic State controlled 90 percent of

the camp after defeating fighters mainly from Aknaf Beit al-Maqdis, a

Syrian and Palestinian militia opposed to Assad.

Islamic State, the most powerful insurgent group in Syria, is now

only a few kilometres from Assad's seat of power. The Palestinian

official echoed the Syrian government line that the only way to rid the

camp of the ultra-radical militants was through force.

"What we have agreed with our Syrian brothers and factions is that

the options that existed for a political solution were closed by the

fighters of Daesh," he said, using a derogatory term for Islamist State.

"The crimes they have committed ... left us with no choice except a

security one that respects the partnership with the Syrian state," he

told a news conference in Damascus.

The Observatory has said Syrian air force jets had been waging a

bombing campaign on militant hideouts in the camp almost daily since

Islamic State fighters infiltrated from the adjacent, rebel-held Hajar

al Aswad neighbourhood.

The United Nations has said it is extremely concerned about the

safety and protection of Syrians and Palestinians in the camp. Civilians

trapped there have long suffered a two-year government siege to force

rebels to capitulate that has led to chronic food shortages and disease.

UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon told reporters in New York the camp

was beginning to resemble "a death camp" with its residents facing "a

double-edged sword: armed elements inside the camp and government forces

outside."

Ban warned that any "massive assault on the camp and all civilians

would be yet one more outrageous war crime for which those responsible

must be held accountable.

"We simply cannot stand by and watch a massacre unfold," he said.

#Yarmouk resembles 'death camp': UN Secretary General #YarmoukRefugeeCamp.: image via SBS News @SBSNews, 9 April 2015

#Yarmouk resembles 'death camp': UN Secretary General #YarmoukRefugeeCamp.: image via SBS News @SBSNews, 9 April 2015

Left to their fate

Destroyed buildings in the Yarmouk refugee area of Damascus, Syria: photo by Youssef Badawi/EPA via The Guardian, 10 April 2015

'Yarmouk is being annihilated': Palestinians in Syria are left to their

fate: Close to Damascus, refugees who survived a siege by Bashar

al-Assad’s

forces and assault by Isis endure merciless shelling and have ‘no food,

electricity or water’: Kareem Shaheen in Beirut, The Guardian,10 April 2015

If they are lucky, Ahmad and his family in the Yarmouk refugee camp

will have one meal today: two plates of rice cooked with undrinkable

water. Others will have to do with less, perhaps a bowl of spiced water

that doubles as a form of soup that will do nothing to ease the

all-too-familiar hunger pangs.

“We are being killed here, Yarmouk camp is being annihilated,” said

Ahmad, a resident of the Palestinian camp just a few miles from the

centre of the Syrian capital who was given a pseudonym to protect his

identity.

Yarmouk, once a bustling southern suburb of Damascus of 200,000

people, has been starved for two years in a relentless siege by Bashar

al-Assad’s regime, which has also blocked water supplies for months, a

tactic that activists say constitutes the use of water as a tool of war.

Now

the remaining 18,000 residents, many of whom suffer from ailments

ranging from malnourishment to liver disease and illnesses linked to

consuming tainted water, are mired on the frontline of the latest

offensive of the terror group Islamic State, which has seized the

majority of the camp.

“The situation inside the camp is catastrophic,” said Ahmad. “There

is no food or electricity or water, Daesh [Arabic acronym for Isis] is

killing and looting the camp, there are clashes, there is shelling.

Everyone is shelling the camp.

“As soon as Daesh entered the camp they burned the Palestinian flag and beheaded civilians,” he said.

Activists from the camp say that between 2,000 and 4,000 residents

have fled, seeking refuge in nearby villages such as Yalda, Babila and

Beit Sahem in the Damascus countryside, but those who stayed inside face

a grim future.

Food prices have rocketed, with a loaf of bread costing more than $10

(£6.80). Malnourished residents have to walk miles to buy food on the

road to Yalda, whose residents are benefiting from a local ceasefire

deal between the regime and the opposition. But most residents choose

instead to remain in their homes to avoid being killed in the crossfire

of clashes, snipers or barrel bombs.

Nearly 200 people are believed to have died in Yarmouk in 2014 due to

hunger. Medical supplies are also badly needed, with a lack of

equipment, antibiotics and painkillers to treat the wounded, said Salim

Salamah, head of the Palestinian League for Human Rights-Syria and a

former Yarmouk resident.

Activists from Yarmouk said that prior to the Isis offensive, camp

residents and those who fled recently had experienced numerous cases of

jaundice, in addition to malnourishment, dehydration and psychological

illnesses including depression and symptoms of post-traumatic stress

disorder.

Palestinians with a placard

reading ‘Yarmouk camp ... we need you to stop the barrel bombs’

demonstrate in a refugee camp near Sidon, Lebanon: photo by Mohammed Zaatari/AP via The Guardian, 10 April 2015

“After Daesh entered, the situation worsened because they stole the

remaining medical supplies and [there was an] increase in the arbitrary

bombings with mortars, rockets and barrel bombs,” said Sameh Hammam, the

pseudonym of an activist who fled to the camp’s outskirts in the latest

assault.

There are only two hospitals in the camp, with a tiny number of

doctors. One of them, the Palestine hospital was hit with a regime

barrel bomb on Thursday, activists said.

But beyond the humanitarian crisis, many Palestinians from Yarmouk

feel abandoned by the Arab world and the international community at

large, bridling at the lack of concern for residents who endured two

years of siege. Thousands of their compatriots had fled in the past,

including to neighbouring Lebanon where they have extremely limited

rights.

Many have perished as they tried to make the journey by boat to

Europe, and some have secured homes in exile through resettlement in

places such as Sweden, Denmark and Germany.

“What I feel and most of the people who left and survived feel is

complete disappointment and absolute sadness, and a feeling of betrayal …

most importantly from the international community,” said Salamah,

saying the lack of concern for the suffering of the Palestinians in

comparison to the alarm at the rise of Isis showed disregard for the

lives of civilians starving to death in the 21st century.

“There’s a serious crisis of morality and humanity about what’s going

on in Syria, from north to south, not only in Yarmouk,” he said.

A Palestinian academic who visited Yarmouk six months ago on a

humanitarian mission said some locals were reduced to consuming water

mixed with spices, adding that the Palestinians were paying the price

“of struggles that they are not a part of”.

“I’m not just angry but indignant at this frightening silence,” he

said. “Decisions are taken at the security council that are worthless

and not enforced. The whole world is lying to us.

“I think sometimes that we do not belong to this world, that the

Palestinian people are not part of humanity,” he added. “I don’t think

there’s a light for the Palestinians at the end of the tunnel, except if

the tunnel leads to Stockholm or Berlin.” He said that the Palestinians

now needed a saviour or messiah, one who could save them from being

deprived of even the basic necessity of existence.

“Is there anything worse than dying of hunger?” he asked.

Isis closes in

The population of Yarmouk has fallen from 200,000 to just 16,000 since the Syrian government’s siege began. An estimated 600 Isis fighters now control most of the camp: photo by AP via The Guardian, 10 April 2015

Isis closes in on Damascus after seizing Yarmouk refugee camp: The terrorist group’s capture of the beleaguered site means it now controls territory only six miles from the centre of the Syrian capital: Martin Chulov and Kareem Shaheen in Beirut via The Guardian, 10 April 2015

For more than 50 years, Yarmouk refugee camp was used as a showpiece of Syrian support for the Palestinian cause.

Now, after three years of war and siege, jihadists of the Islamic State

(Isis) stalk its ruins, the regime bombs the buildings that still stand

and the few remaining residents must choose between abject misery if

they stay and likely death if they flee.

More than anywhere else in Syria,

the fight for Yarmouk –- especially since Isis stormed the camp on 9

April -– has captured the shifting allegiances and, at times, cynical

complexities that now define the myriad battlefields across the ruined

country.

Most of the 200,000 or so Palestinians who lived in Yarmouk until

late 2012 are now second-time refugees, either elsewhere in Syria,

across the border in Lebanon or in Jordan.

Their leaders, meanwhile, remain deeply factionalised, unable to ease

the regime siege or to stem the flow of the jihadists, who stormed the

camp after four months of organising on the doorstep of Damascus,

potentially changing the face of the fight for the capital.

Activists, diplomats and former camp residents contacted by the

Guardian said recent events may end up proving decisive in the fight for

central Damascus, only six miles north of the camp, which is in effect a

suburb of the city.

With the shock of the jihadist incursion subsiding, the narrative of

the regime siege is starting to change. Syrian officials have offered to

rescue civilians, to whom they had denied safe refuge for more than two years.

The jihadists are also attempting to claim a relative moral high ground

by insisting that only they can break the blockade, after the failure

of the armed opposition and the Palestinian leaders to do so.

“They

are now casting themselves as saviours of the Palestinians after

besieging them for all that time,” said a western diplomat in Beirut of

the regime of Bashar al-Assad. “They want to be seen as liberators, not

persecutors, and this cause has worked very well for them in the past.”

Activists said that Isis, although present in the Hajar al-Aswad

neighbourhood south of Yarmouk for at least the past six months, was not

seen as a threat to the militant groups opposing the regime from within

its borders, or to its estimated 16,000 residents.

The neighbouring Yalda area had remained relatively calm for the past

year as a result of a locally negotiated ceasefire between regime and

opposition forces, as had the surrounding area, despite Isis’s attempts

to slowly gain a foothold.

Most of the estimated 600 Isis fighters who now control up to 80% of

Yarmouk are local men who were previously aligned to other opposition

groups, camp insiders say. Some of the militants had previously been

exiled, and most of those who returned were smuggled in by the

al-Qaida-aligned Jabhat al-Nusra, which remains a staunch foe of Isis in

northern Syria.

“They mostly had a bad reputation and were known for thievery,” one

activist said of the jihadists now in control of Yarmouk. In northern

and eastern Syria, foreign jihadists led predominantly by veterans of

the Iraqi civil war are immersed in more of an ideological fight.

“[Isis] is coming back today to take revenge from the civilians who

evicted them, but people were unable to stand up to them because of

their savagery and the fact they were well armed with medium and light

weapons,” said the activist who fled to the camp’s outskirts.

Over the past five days, Syrian helicopters have dropped up to 12 barrel bombs on the camp,

while reinforcing its borders to the west. Now that Isis controls the

area, which is roughly five miles square, its fighters appear to be as

hemmed in as the remaining civilians.

“They’ve walked into a trap from which there is no escape,” the diplomat said.

The Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) has maintained a low

profile throughout the siege, which has repeatedly been described by the UN Relief and Works Agency

(UNWRA) as an atrocity. Throughout the past two years, the UN body has

only been able to secure piecemeal access to starving residents, some of

whom have died from hunger and thirst.

“The violence that began in Yarmouk on 9 April is not just

continuing, it has intensified,” said UNRWA spokesman Chris Gunness.

“Yarmouk is at the lower reaches of hell. It must not be allowed to

descend further.”

“The situation is different now,” said Fathi Aboul Ardat, the PLO

official in Lebanon, describing the arrival of Isis inside Yarmouk as a

dangerous and unprecedented step.

When asked whether the PLO could deal with the regime, which has

imposed a two-year siege on Yarmouk, he replied: “We deal with a state.”

A Palestinian academic from Yarmouk who visited the camp late last

year said the PLO’s overtures to the regime are part of an internal

competition between Fatah, which dominates the PLO, and Hamas, which

fell out with Assad after it declared its support for the original

uprising.

“All of the Palestinian organisations have been unable to rescue the

Palestinians,” he said. “We need salvation. We are in the 21st century

and Palestinians are dying of hunger.

“It’s not that they are selling out the Palestinians. They are

incapacitated. The Palestinian organisations are like the former Ottoman

Empire; they are the sick man.”

The Worst Place

Palestinian refugees in Yarmouk, Damascus, queueing for food: photo by AP, 31 January 2014 via The Guardian, 10 March 2015

How Yarmouk refugee camp became the worst place in Syria: Yarmouk, near the centre of Damascus, prospered as a safe haven for

Palestinians. Under siege, it is now a prison for its remaining

residents, who survive on little food and water, with no hope of escape: Jonathan Steele, the Guardian, 5 March 2015

On 18 January 2014, barely five miles from the centre of Damascus –-

with President Bashar al‑Assad’s office complex visible in the distance –-

a small crowd of desperate people emerged from a seemingly uninhabited

wasteland of bomb-shattered buildings. News had spread throughout

Yarmouk, a district of the capital that is home to Syria’s largest

community of Palestinians, that the government and rebel groups had

agreed to allow a delivery of food, briefly opening a crack in a

year-long siege that had starved the area’s civilians and caused dozens

of deaths.

Families had sent their strongest members to collect the newly

arrived supplies, and the hungry throng filled the entire width of a

street, throwing up dust in the morning light. The relief workers making

the delivery recalled one woman, gaunt with malnutrition, who fell down

and was too weak to rise. She died on the spot. The scenes were such

that some of these experienced aid workers needed trauma counselling

when they returned to headquarters in Damascus.

There was only enough food for a few hundred families. Thousands of

disappointed people staggered home empty-handed. But officials from the

UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), established to aid Palestinian

refugees throughout the Middle East, hoped that the delivery had set a

precedent. They had not publicised it in advance -– there was concern

that excessive attention would anger the Syrian government –- and were

reluctant to invite journalists to observe a mission that might have

been aborted for security reasons. Four days earlier, an attempted

delivery had been abandoned after a mortar exploded very close to the

convoy.

After the successful delivery on 18 January, UNRWA officials decided

discretion was no longer the best policy. On 31 January, a convoy

delivering food to Yarmouk was accompanied by a local photographer, who

took a picture of the vast crowd surging through a street lined with the

ruins of destroyed buildings. This image quickly became an emblem of

the Syrian conflict. To draw attention to the plight of the besieged

civilians UNRWA launched a social media campaign (#LetUsThrough) in

which millions clicked on a petition to put the image on two of the

world’s highest-profile billboards. In Times Square, New York and the

Shibuya district of Tokyo people stood in front of giant screens taking

selfies, which were then beamed back to Yarmouk as a show of solidarity.

This

was how Yarmouk entered the world’s consciousness: a refugee camp

designed as a safe haven for the Palestinian diaspora that had become

the worst place on earth. No electricity for months. No piped water. No

access for food. Worse still, no chance for people to leave or return,

except for a handful of emergency medical cases or the few who had the

means to pay people-smugglers to get them through the multiple

checkpoints. Some called it Syria’s Gaza, but its plight was even worse,

because the siege was more comprehensive; Yarmouk was a prison from

which there was no escape.

But notoriety can be short-lived. When Gaza came under Israeli

bombardment in July 2014 and the world’s media rushed to report the

carnage, Yarmouk slipped back into obscurity. The opening in the siege

that UNRWA had negotiated in January 2014 applied only fitfully

throughout the year: food deliveries were only possible on 131 days, and

often less than half the amount required got through. Since 6 December,

the siege has once again become impassable. UNRWA reports that it has

not been able to deliver any food at all for the past 12 weeks. “We are

getting new reports of people dying of malnutrition and of women dying

in childbirth, but nothing can be confirmed,” said Chris Gunness,

UNRWA’s spokesperson. Unlike in Gaza, where UNRWA has several offices,

the organisation cannot enter Yarmouk at all.

For Yarmouk to become a spectacle of suffering far worse than Gaza marked an indelible stain on the mantle that Bashar al-Assad inherited from his father. Hafez al-Assad: photo by Enric Marti/AP via The Guardian, 5 March 2015

As Syria’s civil war enters its fourth year, other towns and villages

are suffering long sieges, usually by Assad’s forces but sometimes, as

in the case of Nubul and Zahra, two Shia villages north-west of Aleppo,

by anti-Assad rebels. Still, Yarmouk stands out, partly because of the

large number of trapped civilians – estimated to be around 18,000 -– but

also because of its political significance. Hafez al-Assad, who ruled

Syria for three decades before power passed to his son on his death in

2000, cast his country as the cornerstone of the Arab “axis of

resistance” against Israel. This required that he be seen as the supreme

defender of Palestinian rights; a leader who would ensure that

Palestinian refugees in Syria lived better than those anywhere else in

the Middle East. For Yarmouk to come under the control of anti-Assad

rebels, and then be bombarded by government forces -– to become a

spectacle of suffering far worse than Gaza –- marked an indelible stain

on the mantle that Bashar al-Assad inherited from his father.

***

Before the Syrian civil war began, Yarmouk was home to 150,000

Palestinians. Though people still refer to it as a “camp”, tents were

replaced with solid housing soon after its founding in 1957. In time it

became just another district of Damascus. As well as being home to

Syria’s largest community of Palestinian refugees, it also housed some

650,000 Syrians.

Nidal Bitari, a co-founder of the Palestinian Association for Human

Rights in Syria, fled the country at the end of 2011 after being tipped

off that he was wanted by the Assad regime’s security services. But,

like most of the Palestinians in Yarmouk, he wanted to stay neutral when

the uprising began. As Bitari wrote in a detailed account of Yarmouk's recent political history

published in 2013, Palestinians in Syria lived under better conditions

than in any other Arab state: “By law they enjoy almost all the rights

and benefits of Syrian nationals except citizenship and the right to

vote. They have full access to Syrian schools and universities on the

same basis as citizens … And because their numbers are tiny compared to

the general Syrian population (less than 2%), the refugees were never

perceived as a threat, and the degree of integration between

Palestinians and Syrians –- through work, education, and intermarriage –-

has no parallel in the Arab world.”

When I first visited Yarmouk in March 2003, it was a hotbed of anger

towards the American invasion of Iraq, which had just began. While other

Arab countries muted criticism of US policy or quietly supported George

W Bush and Tony Blair, the Syrian state media was full of

denunciations. Scores of young Palestinian men from the camp had crossed

into Iraq to fight the Americans, often disappearing without telling

their own families.

I came across a wake in one narrow back street. It was the third day

of mourning for a young man named Issam. He had telephoned home for the

first time as he was about to cross into Iraq. In a bus from Damascus

with other volunteers from half a dozen Arab countries, the young

Palestinian told his father that he and two cousins were going off to

war. Six days of silence followed, as his family watched TV footage from

Iraq even more intently than before. Then one of the cousins phoned:

Issam had never even reached Baghdad. Less than five hours after calling

his parents, he died in a hail of fire from a US helicopter. Thirteen

other unarmed men in the three buses were killed. The cousin escaped

with minor wounds.

When Syrians began to rise up in protest against the government of Bashar al-Assad in March 2011,

the situation threatened to unsettle the relatively stable position of

Palestinians within the country. Palestinian groups were closely

monitored by the Syrian security services and they were expected to

remain uninvolved in the nation’s politics.

According to Bitari, the

trigger for Yarmouk’s entrapment in the intensifying conflict came from

the Syrian government rather than the opposition. In May 2011, during

the preparations for Nakba Day,

which commemorates the expulsion of Palestinian refugees during the

creation of Israel in 1948, representatives of the Assad regime began to

promote the idea of a demonstration at the Israeli border on the Golan

Heights.

Bitari and his friends were wary, suspecting that the regime wanted

to divert attention from the internal uprising. He described their

decision to form a “youth coalition of Palestinians” in Yarmouk to

coordinate decisions pertaining to the camp, which included

representatives from each of the Palestinian political factions inside.

The group’s first meeting concerned the Nakba Day protests, and a

majority opposed any participation. But on the morning of Nakba Day the

government supplied buses, which hundreds of people got on. At the

border, the Syrian army let the buses through the demarcation lines and

several protesters climbed the fence that blocks access to

Israeli-controlled territory. Israeli troops used tear gas and live

rounds. Three people died.

A month later, on Naksa Day –- the anniversary of the defeat of Arab

armies by Israel in the 1967 six-day war -– minivans sent by Syrian

security took about 50 Yarmouk residents to the border, where they were

joined by several hundred other young people. Syrian state TV cameras

were on hand to film what happened. Again people tried to scale the

fence, and this time 23 were shot dead by Israeli forces -– 12 of them

from Yarmouk, according to Bitari.

Though the Israelis fired the bullets, “the rage was almost as great

against the factions for not doing anything to stop the bloodshed”, as

Bitari said. The next day the funeral of the victims was attended by

30,000 people.

Angry

mourners surrounded the headquarters of the Popular Front for the

Liberation of Palestine -- General Command (PFLP-GC). A small faction

led by Ahmed Jibril, which rejected the Oslo accords,

the PFLP-GC was a firm supporter of the Syrian government and was seen

by many residents as the regime’s enforcer in the camp. When a PFLP-GC

security guard shot and killed a 14-year-old boy, the crowd stormed the

building and set it on fire. Jibril had to be rescued by the Syrian

army.

This event embarrassed Bashar al-Assad and encouraged Syrian

opposition groups to see Yarmouk as a potential support base for the

uprising against him. Yarmouk’s geographical position, wedge-shaped with

its apex pointing at the heart of Damascus, gave it strategic value.

The district was bordered by two poorer Syrian suburbs, al Hajjar al

Aswad and Tadamon, which were already being infiltrated by opposition

fighters. To the south was open countryside, which was easy for them to

move through.

Bitari and his friends still hoped to keep Yarmouk neutral. They were

alarmed when the Syrian government, shaken by the anti-PFLP-GC protest

and the threat of rebel advances, gave Jibril’s men the right to parade

with weapons. This escalation encouraged the Free Syrian Army -– at that

time the main opposition group, backed by western governments -– to plan

to move into the camp and seize it from Syrian government control. The

Palestinian youth coalition’s efforts had failed. The group disbanded in

despair. Civilians who wanted to avoid their district being militarised

and dragged into conflict found themselves isolated. The same dynamic

was affecting most of the rest of the country.

***

For the Free Syrian Army, Yarmouk was a particularly valued prize after Khaled Meshaal, the leader of Hamas

in exile who had lived in Damascus for more than a decade, moved to

Qatar in February 2012. Meshaal felt unable to accede to the Syrian

government’s pleas that he condemn the anti-regime uprising. Instead, he

accepted an invitation from Qatar, one of the armed opposition’s main

financial backers. It was a severe blow to Assad’s credentials as leader

of the axis of resistance.

In December 2012 the FSA and the al-Qaida affiliate, Jabhat al Nusra

were ready for a concerted attack to capture Damascus and topple Assad.

Yarmouk was the gateway to the capital, closer to the centre than any of

the other suburbs where the regime was losing control. The crisis came

to a head on 16 December, when a Syrian air force plane bombed Yarmouk

in what the government later claimed was a mistake. Dozens of civilians

were killed. Brigades from the FSA and Jabhat al Nusra seized the

opportunity to enter the camp –- and in response, the government launched

a hail of artillery shells, turning most buildings on the edge of the

district to rubble.

A girl receives soup from Kafaf, a charitable foundation, in Yarmouk: photo by Reuters via The Guardian, 10 March 2015

Within

a few days most of the PFLP-GC, the main Palestinian faction

supporting the Assad regime, had fled Yarmouk; some defected to the

rebels who went on to gain full control. Hundreds of thousands of

civilians left. The Syrians of Yarmouk mainly went to relatives and

friends in central Damascus or other cities, or moved to Lebanon and

Jordan. Palestinians fled to what they hoped would be safer areas inside

Syria. Although rebel efforts to capture the rest of Damascus failed,

Yarmouk

remains in rebel hands today. Some 18,000 civilians still live there,

including anywhere between 1,000 and 4,000 Syrians. Still, it is clear

that Yarmouk has reverted to being a largely Palestinian enclave.

Assad’s government responded to its defeat in Yarmouk by putting the

area under siege.

For a few months food could still be brought in from

the rural areas to the south, though profiteering was intense. In July

2013 the government tightened its grip and the siege became almost

total. Inside Yarmouk fighting erupted between the FSA and Jabhat al

Nusra, the latter of which had set up sharia courts. Spasmodic attempts

were made to relieve the suffering of Yarmouk’s civilians. In the spring

of 2013 Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian president, even proposed that

all of Yarmouk’s 150,000 Palestinian residents move to the West Bank or

Gaza. In November 2013, Abbas sent a team to Damascus to discuss

humanitarian relief and a ceasefire between the rebels and the

government. The idea was to open a safe corridor for the movement of

supplies and displaced civilians, but no deal was ever reached.

In September 2014, I met Abu Akram, a member of the PFPL-GC

leadership, in a flat on the edge of Yarmouk. A tall older man with one

arm in a brace, who moved to Yarmouk from Lebanon in 1994, he had taken

part in the abortive ceasefire negotiations with the Syrian opposition,

whose breakdown he blamed on the Islamists. A tough, battle-hardened

figure firmly allied to the Assad regime, he showed no embarrassment in

defending the siege. It was a legitimate tactic, he claimed, in part

because the food from UNRWA that was allowed into Yarmouk ended up in

the hands of the rebel fighters, for their own use or for sale on the

black market.

“We saw that the armed groups were taking food from civilians,” he

said, then claimed that boxes of aid meant for Yarmouk could be seen for

sale in a nearby district. He even criticised the decision to relax the

pressure in early 2014. “It was a mistake to break the siege,” he said.

“If we had continued by another week, hunger would have forced them to

give up.”

The barbaric nature of sieges has remained unchanged for thousands of

years. The aim is to starve the trapped civilians into submission, in

the hope they will turn against whatever armed faction controls the

territory and persuade them to surrender. The armed faction, in turn,

wants to keep the civilians inside so as to make it less likely the

besieging army will bring destruction upon the captives. Now, in the

21st century, the very same tactics are being deployed not only in

Yarmouk but in several other parts of Syria.

***

Sieges fuel a war economy in which those who man the checkpoints can

run a lucrative business selling permission to leave or return. They

encourage smuggling of people and food, and keep prices in the camp’s

few markets artificially high. When I visited Yarmouk’s northern

entrance in September 2014, I found nothing but bleakness. Syrian

government soldiers stood guard near a crossroads known as Batikha -–

“watermelon” –- Square, so named for a green monument of a globe that

stands amid a clump of palm trees in the middle of the street. The only

route into the camp required a walk through a narrow alley between two

five-storey buildings that had most of their windows blown out. The

neighbouring alley was shielded by huge white padded sheets strung from

the upper floors of buildings on either side –- makeshift screens

intended to stop rebel snipers from targeting anyone walking in the

square.

A young woman in hijab was standing near the entrance, weeping as she

and a male companion talked with the officer in charge of the

checkpoint. After a few minutes of conversation that ended on what

looked to be a frustrating note, the woman and her friend pulled back,

then wandered up and down the street, apparently debating whether to try

another tack to convince the officer or just give up and leave.

Palestine refugees in Yarmouk queue for food distributed by UNRWA: photo by HOPD/AP via The Guardian, 10 March 2015

“I am trapped,” the woman, named Reem Buqaee, told me. She had been

given permission to leave Yarmouk three months earlier with her three

teenage daughters. The oldest one was pregnant. Owing to malnutrition,

she was suffering from anaemia so severe that she was at risk of losing

her baby. The other two girls also had medical problems. But leaving the

camp had meant splitting the family. The husband of the pregnant woman

could not leave the camp, nor could Reem’s husband, or her 16-year-old

son. Rebel groups were eager to keep people in the camp, she said,

particularly men and boys. Their departure was seen as defection from

the opposition cause as well as potentially making it easier for

government troops to enter the camp by force and regain control.

Buqaee’s daughter had safely given birth and the other girls had

regained their strength, so she wanted to take them back into Yarmouk.

“I had to choose between living in a prison under siege but alongside my

husband and son, or stay outside Yarmouk separated but free,” she said.

On this particular day, she had come to the camp entrance to see

whether her request to return had been granted, but the officer told her

he had not received orders to let her and her daughters and baby

grand-daughter inside. “Our house is only 100 metres from here, just

inside the camp. It’s so near but very far,” she said.

The next day, I visited Buqaee at an overcrowded flat in the Dummar

suburb of Damascus, where a distant relative had given her and her

daughters temporary shelter. A thick atmosphere of fear surrounds any

discussion of Yarmouk. This affects everyone from UNRWA officials to

Yarmouk residents. People worry that their families will suffer if they

publicly attribute blame to the regime or the rebels for the siege, the

collapse of ceasefire talks, and the impossibility of escaping. UNRWA

officials are concerned about losing the minimal access they have to

Yarmouk if they say anything that might be misinterpreted by one side or

the other. When I spoke to residents who had left the camp for other

parts of Damascus, but who talk regularly with siblings and parents

still inside, they refused to be quoted, explaining that people are

scared of reprisals from both the regime and the anti-Assad forces

inside the camp.

Buqaee, however, described the horrors of the siege without

hesitation: women dying in childbirth, infants killed by malnutrition.

There was no anger or hysteria in her voice, just a calm recollection of

facts. “You couldn’t buy bread. At the worst point a kilo of rice cost

12,000 Syrian pounds (£41), now it is 800 pounds (£2.75) compared to 100

Syrian pounds (34p) in central Damascus. It was 900 pounds (£3.10) for a

kilo of tomatoes, compared to 100 here,” Reem recalled. “We had some

stocks but when they gave out we used to eat wild plants. We picked and

cooked them. In every family there was hepatitis because of a lack of

sugar. The water was dirty. People had fevers. Your joints and bones

felt stiff. My middle daughter had brucellosis and there was no

medication,” she said. In October 2013, in a sign of how bad things had

become, the imam of Yarmouk’s largest mosque issued a fatwa that

permitted people to eat cats, dogs and donkeys.

The relaxation of the siege in January last year was limited and

insecure, she said. UNRWA’s food deliveries were regularly cut short by

mortar explosions and sniper fire. No one was sure who began firing or

why. She remembered one incident vividly: “It was March 23. I had gone

to collect a food parcel and was on the way back when a mortar went off.

Twenty-nine people were killed. My daughter’s husband had come to help

carry the boxes. He was hit by shrapnel and cannot walk now. It’ll take

him another three or four months to get better.”

For most of 2014, both sides were willing to allow some humanitarian

supplies to enter the camp on an ad hoc basis, UN officials told me,

even if the amount was far below what was needed. Every day, UNRWA would

check whether there had been exchanges of fire in Yarmouk. Sometimes

the agency’s minivans never left the warehouse in central Damascus, on

other occasions, delivery convoys were turned back. “We never say we’ve

had access. All we say is that they’ve given us some opportunities to

provide aid,” one UN official said.

UNRWA has not yet been able to enter the camp to conduct a needs

assessment. Since the graphic scenes of starving masses early last year,

the agency developed a more orderly process, with lists of people who

are allowed to cross the no man’s land at the edge of the camp once each

month to collect food parcels. Each parcel contains five kilograms of

rice, five kilograms of sugar, five kilograms of lentils, five litres of

oil, five kilograms of powdered milk, one kilogram of halva, one and a

half kilograms of pasta and five 200g tins of luncheon meat. This is

designed to feed a family of eight people for 10 days. In other parts of

Syria where displaced Palestinians are living, UNRWA provides cash so

that people can buy food for the rest of the month, but in Yarmouk that

has not been not possible.

Providing medical supplies is sensitive, since the Syrian government

fears they will go to wounded fighters. Initially it only gave

permission for rehydration salts and basic painkillers. UNRWA eventually

managed to operate a mobile health clinic at the food distribution

point, which provided basic treatments for communicable diseases and

other infections, as well as conditions such as diabetes and

hypertension. Tests conducted in 2014 on a random sample of patients

found that 40% had typhoid.

Education has been dramatically affected by the siege. According to

residents inside the camp, all of Yarmouk’s 28 schools have been closed,

and volunteer teachers hold informal classes in 10 “safe spaces”,

including the basements of mosques. The lack of electricity means

children have to do their homework by generators if their parents can

afford the fuel for them, or by candlelight. The spotlight that the

UNRWA has tried to keep on Yarmouk may have acted as some restraint on

government forces – the area has not been bombed as heavily as other

rebel-held districts of Damascus. But this is only a crumb of comfort.

“Conditions are far worse than Gaza,” said one UN official.

“Palestinians always had dignity, hope, resilience. Now after four years

of war I see people giving up. They find it hard to accept there are no

options”.

***

The latest attempt to reach a ceasefire and end the siege of Yarmouk

was last June, when the armed groups inside the camp and some civilian

representatives signed a pact with 13 representatives of the Assad

government, which would have seen gunmen leave Yarmouk after the

creation of a new security force to defend the camp. The deal was never

implemented.

Nidal Bitari now lives in the United States, where he remains in

daily contact with friends in Yarmouk by phone and Skype. He lobbied at

UN headquarters in New York for western governments to support the June

ceasefire agreement, and blames them, along with supporters of Jabhat al

Nusra, for letting the deal collapse. “I suppose this initiative went

against the wishes of France, UK and USA,” he said, “as their policy is

based on supporting the interim government in exile, and they believe

such truces give legitimacy to the regime.” Talal Alyan, a