Word of the day: "stravaig" - to wander without fixed purpose, to roam aimlessly for pleasure. (Scots): image via Robert Macfarlane @RobGMacfarlane, 19 March 2017

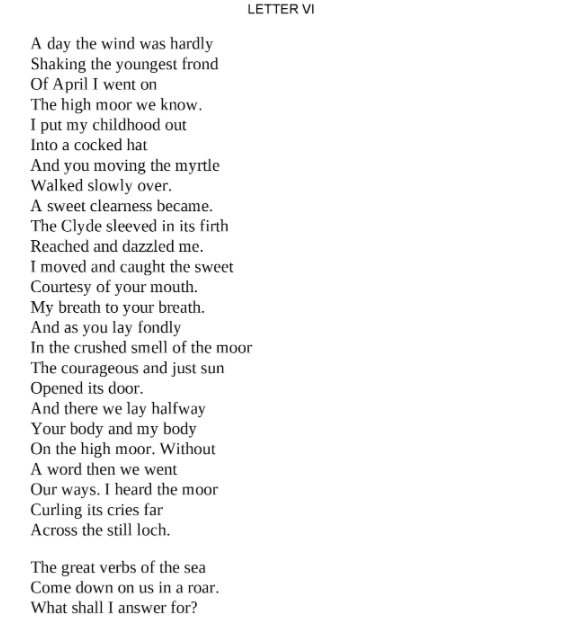

"I heard the moor Curling its cries far Across the still loch." WS Graham's pronouns and prepositions dance so strangely in this great poem. [Text: W.S. Graham 1918-1986: Letter VI, 1955]: image via Robert Macfarlane @RobGMacfarlane, 19 March 2017

"Often the mountain gives itself most completely when I have no destination...but have gone out merely to be with it." (Nan Shepherd): image via Robert Macfarlane @RobGMacfarlane, 19 March 2017

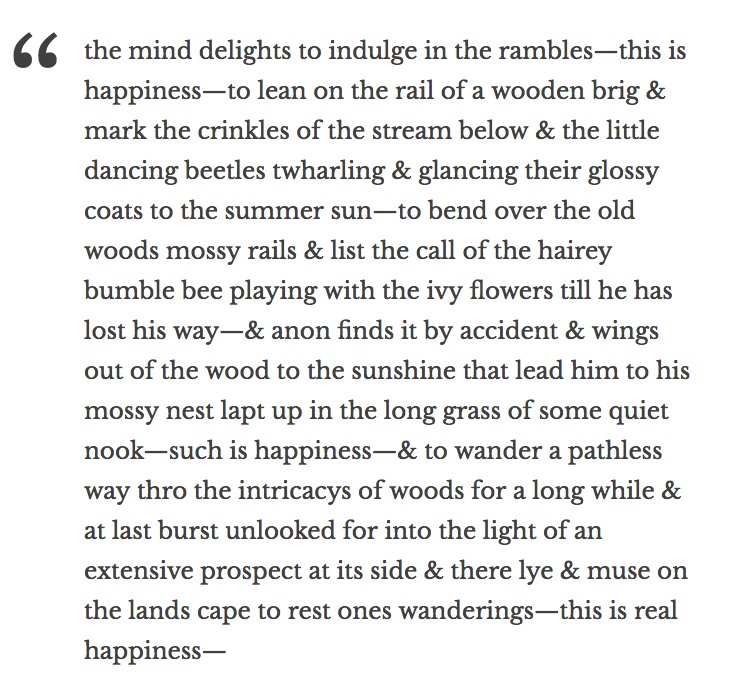

"His words are better viewed as creaturely: they are alive with difference." @zacharyrosenau fascinating on John Clare. Ty @KeithArsenault: image via Robert Macfarlane @RobGMacfarlane, 16 March 2017

W.S. Graham: Letter VI

A day the wind was hardly

Shaking the youngest frond

Of April I went on

The high moor we know.

I put my childhood out

Into a cocked hat

And you moving the myrtle

Walked slowly over.

A sweet clearness became.

The Clyde sleeved in its firth

Reached and dazzled me.

I moved and caught the sweet

Courtesy of your mouth.

My breath to your breath.

And as you lay fondly

In the crushed smell of the moor

The courageous and just sun

Opened its door.

And there we lay halfway

Your body and my body

Over the high moor. Without

A word then we went

Our ways. I heard the moor

Curling its cries far

Across the still loch.

The great verbs of the sea

Come down on us in a roar.

What shall I answer for?

W.S. Graham (1918-1986): Letter VI (1955)

Carn Galva, West Penwith, Cornwall. Carn Galva, west Penwisth, Cornwall. A view looking west from the summit of Carn Galva on a fine June day. Carn Galva is 230 metres above sea level and the second highest hill on the Land's End peninsula - it looms over the coastal plain from Zennor to Morvah. In the middle distance (partly in shadow), can be seen the flanks of Watch Croft - which is the highest point by a few metres. The name of the hill comes from the old cornish "carn guillea" - meaning 'rock pile in a high look out'. Early communities may have believed that these granite outcrops had been fashioned by the gods - and that the spirits of the gods dwelt in them. From the summit of the hill you are greeted with a sweeping vista across the wild heathland, described by D.H. Lawrence as "a bareness ancient and inviolable". The twin ruined engine houses of Carn Galver mine can be seen to the right in the middle distance with Bosigran Castle further to the right. It is also possible to spot Pendeen Lighthouse just left of centre in the far distance.: photo by saffron100_uk, 5 June 2014: photo by saffron100_uk, 5 June 2014

Carn Galva, West Penwith, Cornwall. Carn Galva, west Penwisth, Cornwall. A view looking west from the summit of Carn Galva on a fine June day. Carn Galva is 230 metres above sea level and the second highest hill on the Land's End peninsula - it looms over the coastal plain from Zennor to Morvah. In the middle distance (partly in shadow), can be seen the flanks of Watch Croft - which is the highest point by a few metres. The name of the hill comes from the old cornish "carn guillea" - meaning 'rock pile in a high look out'. Early communities may have believed that these granite outcrops had been fashioned by the gods - and that the spirits of the gods dwelt in them. From the summit of the hill you are greeted with a sweeping vista across the wild heathland, described by D.H. Lawrence as "a bareness ancient and inviolable". The twin ruined engine houses of Carn Galver mine can be seen to the right in the middle distance with Bosigran Castle further to the right. It is also possible to spot Pendeen Lighthouse just left of centre in the far distance.: photo by saffron100_uk, 5 June 2014

: photo by saffron100_uk, 5 June 2014

1

Ness, shall we go for a walk?

I'll take you up to the Gulvas

You never really got to.

Put on your lovely yellow

Oilskin to meet the weather.

2

This bit of the road, Ness,

We know well, is different

Continually. Macadam

Has not smoothed it to death.

When the light keeks out, the road

Answers and shines up blue.

I thought we might have seen

Willie Wagtail from earlier.

Nessie, how many steps

Do we take from pole to pole

Going up this hill? I see

Your Blantyre rainy lashes.

The five wires are humming

Every good boy deserves

Favour. We have ascended

Into a mist. And this

Is where we swim the brambles

And catch the path across

The late or early moor

Between us and the Gulvas.

3

Hold on to me and step

Over the world's thorns.

We shall soon be on

The yellow and emerald moss

Of the Penwith moor.

Are you all right beside me?

What's your name and age

As though I did not know.

Are we getting older

At different speeds differently?

4

No, that's not it. The Gulvas

Cannot be seen from here.

Have we left it too late

Maybe the Gulvas is too

Far on a day like this

For us what are our ages

What are our foreign names

What are we doing here

Wet and scratched with the Gulvas

Moving away before us?

5

Let us go back. Reader,

You who have observed

Us at your price from word

To word through the rain,

Don't be put down. I'll come

Again and take you on

The great walk to the Gulvas.

Be well wrapped up against

The high moor and the brambles.

Like a bird in the sky.... Looking down from this Cornish Carn made me feel like a bird. The fields unfolded like a green patchaork quilt, the sheep were tiny white dots... the derelict tin mine was a historical reminder of a once major industry. Then the sea, the wonderful sea always full of energy and beauty. I am proud of my roots, my Cornish roots...: photo by Gillie Savage, 19 October 2014

Like a bird in the sky.... Looking down from this Cornish Carn made me feel like a bird. The fields unfolded like a green patchaork quilt, the sheep were tiny white dots... the derelict tin mine was a historical reminder of a once major industry. Then the sea, the wonderful sea always full of energy and beauty. I am proud of my roots, my Cornish roots...: photo by Gillie Savage, 19 October 2014

Like a bird in the sky.... Looking down from this Cornish Carn made me feel like a bird. The fields unfolded like a green patchaork quilt, the sheep were tiny white dots... the derelict tin mine was a historical reminder of a once major industry. Then the sea, the wonderful sea always full of energy and beauty. I am proud of my roots, my Cornish roots...: photo by Gillie Savage, 19 October 2014

Carn Galver, Cornwall: photo by Synwell, 3 July 2009

Carn Galver, Cornwall: photo by Synwell, 3 July 2009

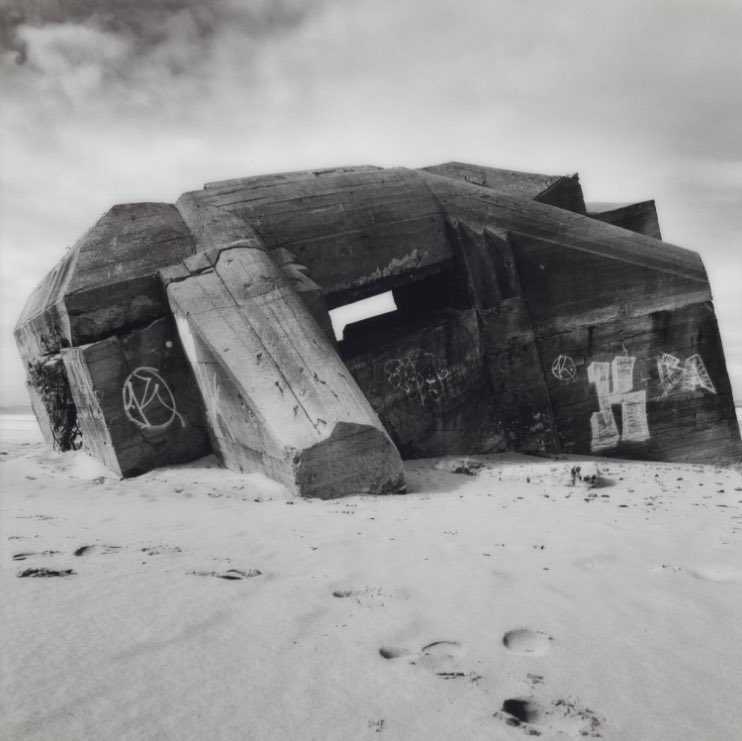

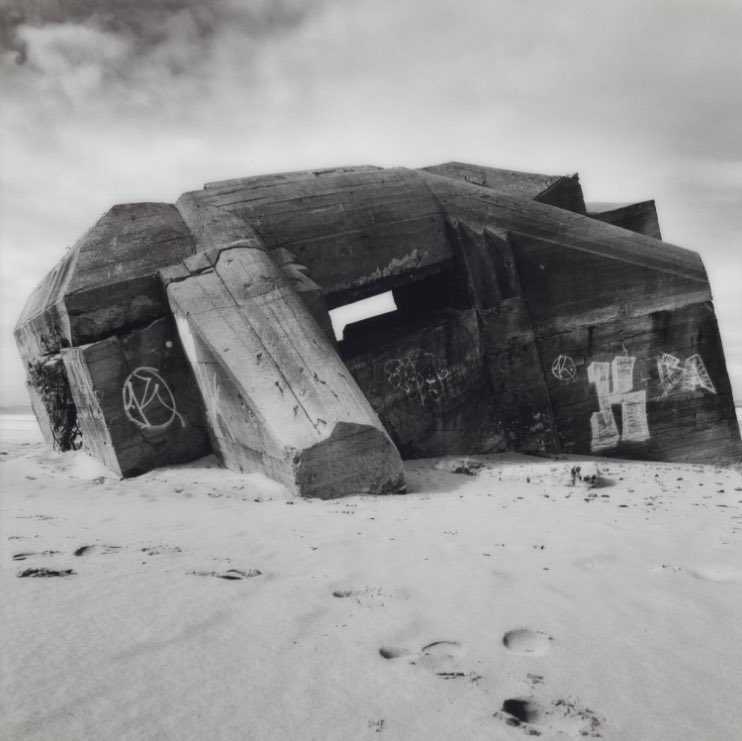

"Ruinenlust has come full circle: we have had our fill". (Rose Macaulay, The Pleasure of Ruins, 1953) Not so, as it turns out.: tweet via Robert Macfarlane @RobGMacFarlane, 17 March 2017

Word of the day: "ruinlust" - the (unseemly) feeling of attraction to abandoned places, crumbling buildings, decaying infrastructure, etc..: image via Robert Macfarlane @RobGMacFarlane, 17 March 2017

Shaking the youngest frond

Of April I went on

The high moor we know.

I put my childhood out

Into a cocked hat

And you moving the myrtle

Walked slowly over.

A sweet clearness became.

The Clyde sleeved in its firth

Reached and dazzled me.

I moved and caught the sweet

Courtesy of your mouth.

My breath to your breath.

And as you lay fondly

In the crushed smell of the moor

The courageous and just sun

Opened its door.

And there we lay halfway

Your body and my body

Over the high moor. Without

A word then we went

Our ways. I heard the moor

Curling its cries far

Across the still loch.

The great verbs of the sea

Come down on us in a roar.

What shall I answer for?

W.S. Graham (1918-1986): Letter VI (1955)

W.S. Graham: A Walk to the Gulvas

Carn Galva, West Penwith, Cornwall. Carn Galva, west Penwisth, Cornwall. A view looking west from the summit of Carn Galva on a fine June day. Carn Galva is 230 metres above sea level and the second highest hill on the Land's End peninsula - it looms over the coastal plain from Zennor to Morvah. In the middle distance (partly in shadow), can be seen the flanks of Watch Croft - which is the highest point by a few metres. The name of the hill comes from the old cornish "carn guillea" - meaning 'rock pile in a high look out'. Early communities may have believed that these granite outcrops had been fashioned by the gods - and that the spirits of the gods dwelt in them. From the summit of the hill you are greeted with a sweeping vista across the wild heathland, described by D.H. Lawrence as "a bareness ancient and inviolable". The twin ruined engine houses of Carn Galver mine can be seen to the right in the middle distance with Bosigran Castle further to the right. It is also possible to spot Pendeen Lighthouse just left of centre in the far distance.: photo by saffron100_uk, 5 June 2014: photo by saffron100_uk, 5 June 2014

Carn Galva, West Penwith, Cornwall. Carn Galva, west Penwisth, Cornwall. A view looking west from the summit of Carn Galva on a fine June day. Carn Galva is 230 metres above sea level and the second highest hill on the Land's End peninsula - it looms over the coastal plain from Zennor to Morvah. In the middle distance (partly in shadow),

can be seen the flanks of Watch Croft - which is the highest point by a

few metres. The name of the hill comes from the old cornish "carn

guillea" - meaning 'rock pile in a high look out'. Early communities may

have believed

that these granite outcrops had been fashioned by the gods - and that

the spirits of the gods dwelt in them. From the summit of the hill you

are greeted with a sweeping vista across the wild heathland, described by D.H. Lawrence as "a bareness ancient and inviolable".

The twin ruined engine houses of Carn Galver mine can be seen to the

right in the middle distance with Bosigran Castle further to the right.

It is also possible to spot Pendeen Lighthouse just left of centre in the far distance.: photo by saffron100_uk, 5 June 2014

Carn Galva, West Penwith, Cornwall. Carn Galva, west Penwisth, Cornwall. A view looking west from the summit of Carn Galva on a fine June day. Carn Galva is 230 metres above sea level and the second highest hill on the Land's End peninsula - it looms over the coastal plain from Zennor to Morvah. In the middle distance (partly in shadow), can be seen the flanks of Watch Croft - which is the highest point by a few metres. The name of the hill comes from the old cornish "carn guillea" - meaning 'rock pile in a high look out'. Early communities may have believed that these granite outcrops had been fashioned by the gods - and that the spirits of the gods dwelt in them. From the summit of the hill you are greeted with a sweeping vista across the wild heathland, described by D.H. Lawrence as "a bareness ancient and inviolable". The twin ruined engine houses of Carn Galver mine can be seen to the right in the middle distance with Bosigran Castle further to the right. It is also possible to spot Pendeen Lighthouse just left of centre in the far distance.: photo by saffron100_uk, 5 June 2014

Ness, shall we go for a walk?

I'll take you up to the Gulvas

You never really got to.

Put on your lovely yellow

Oilskin to meet the weather.

2

This bit of the road, Ness,

We know well, is different

Continually. Macadam

Has not smoothed it to death.

When the light keeks out, the road

Answers and shines up blue.

I thought we might have seen

Willie Wagtail from earlier.

Nessie, how many steps

Do we take from pole to pole

Going up this hill? I see

Your Blantyre rainy lashes.

The five wires are humming

Every good boy deserves

Favour. We have ascended

Into a mist. And this

Is where we swim the brambles

And catch the path across

The late or early moor

Between us and the Gulvas.

3

Hold on to me and step

Over the world's thorns.

We shall soon be on

The yellow and emerald moss

Of the Penwith moor.

Are you all right beside me?

What's your name and age

As though I did not know.

Are we getting older

At different speeds differently?

4

No, that's not it. The Gulvas

Cannot be seen from here.

Have we left it too late

Maybe the Gulvas is too

Far on a day like this

For us what are our ages

What are our foreign names

What are we doing here

Wet and scratched with the Gulvas

Moving away before us?

5

Let us go back. Reader,

You who have observed

Us at your price from word

To word through the rain,

Don't be put down. I'll come

Again and take you on

The great walk to the Gulvas.

Be well wrapped up against

The high moor and the brambles.

W.S. Graham (1918-1986): A Walk to the Gulvas, c. 1980, from New and Collected Poems, 2004

[Gulvas = Graham's version of The Galvers, the hills Carn Galver and Little Galver, in west Cornwall (perhaps influenced by the village name Gulval) -- Matthew Francis]

Like a bird in the sky.... Looking down from this Cornish Carn made me feel like a bird. The fields unfolded like a green patchaork quilt, the sheep were tiny white dots... the derelict tin mine was a historical reminder of a once major industry. Then the sea, the wonderful sea always full of energy and beauty. I am proud of my roots, my Cornish roots...: photo by Gillie Savage, 19 October 2014

Like a bird in the sky.... Looking down from this Cornish Carn made me feel like a bird. The fields unfolded like a green patchaork quilt, the sheep were tiny white dots... the derelict tin mine was a historical reminder of a once major industry. Then the sea, the wonderful sea always full of energy and beauty. I am proud of my roots, my Cornish roots...: photo by Gillie Savage, 19 October 2014

Like a bird in the sky.... Looking down from this Cornish Carn made me feel like a bird. The fields unfolded like a green patchaork quilt, the sheep were tiny white dots... the derelict tin mine was a historical reminder of a once major industry. Then the sea, the wonderful sea always full of energy and beauty. I am proud of my roots, my Cornish roots...: photo by Gillie Savage, 19 October 2014

Carn Galver, Cornwall: photo by Synwell, 3 July 2009

Carn Galver, Cornwall: photo by Synwell, 3 July 2009

"Ruinenlust has come full circle: we have had our fill". (Rose Macaulay, The Pleasure of Ruins, 1953) Not so, as it turns out.: tweet via Robert Macfarlane @RobGMacFarlane, 17 March 2017

Word of the day: "ruinlust" - the (unseemly) feeling of attraction to abandoned places, crumbling buildings, decaying infrastructure, etc..: image via Robert Macfarlane @RobGMacFarlane, 17 March 2017

R.S. Thomas: The Moor

Moorland in the Desert of Wales as seen from the summit of Drygarn Fawr: photo by Velela, 29 March 2009

There were no prayers said. But stillness

Of the heart’s passions -- that was praise

Enough; and the mind’s cession

R. S. Thomas (1913-2000): The Moor, from Pietà, 1966

Tussocks tussocks tussocks. This literally is all there is in this square: tussocks of rough grass, some of it fairly dry (as in the centre of the pic), some more of the reedy sort (as pictured on the left). The land falls off towards the east and south to the source streams of the Afon Tywi. Tussocks!: photo by Rudi Winter, 12 April 2007

Moorland south of Llan Ddu Fawr. The moor climbs steadily towards Llan Ddu Fawr. With a bit of care, the few wet bits can be avoided: photo by Nigel Brown, 12 April 2004

Moorland northeast of Llan Ddu Fawr (2). Looking towards Carnyrhyrddod from near the summit of Llan Ddu Fawr. The peat hags in the middle between the two can be avoided by following an arc to the left. The "Llan" in the name is a corruption of "Lan", short for "Glan", meaning hillside in this context: photo by Nigel Brown, 12 April 2004

Lower slopes of Plynlimon. The track which ends at Llyn Llygad Rheidol passes through typical moorland on the lower slopes west of Plynlimon: photo by Nigel Brown, 2 September 2005

Elenydd moorland west of Pysgotwr, Ceredigion. Beyond the nearby moorland and forest (on Llethr Gwyn) the terrain drops steeply into Cwm Pysgotwr: Photo by Roger Kidd, 13 July 2009

Elenydd landscape south of Llanddewi-Brefi, Ceredigion. Looking across the wide valley of Nant Clywedog-uchaf: photo by Roger Kidd, 18 July 2009

Elenydd Landscape from Carn Penrhiwllwydog, Ceredigion. Across the Doethie valley, the drovers' road climbs from left to right, on its way to Soar-y-Mynydd. To the right of centre, Nant y Benglog plunges down towards the Doethie Fawr. On the skyline to the left is the summit of Drygarn Fawr (height 641 metres -- 2103 feet) 7 miles distant (12.5km): photo by Roger Kidd, 18 September 2007

Elenydd Landscape from Bryn Mawr, Ceredigion. Much of the land here is now designated "open access", which is not to the liking of some landowners on the south side of the Doethie Fawr. Walkers are advised to comply correctly with access regulations in this area: photo by Roger Kidd, 18 September 2007

Edge of Tywi Fechan forest. Looking from the edge of the forest (which is a little north from where the map suggests due to felling) onto the open moorland to the south. The two parallel ridges are Cefn y Cnwc (centre) and Pen y Maen (right/west): photo by Rudi Winter, 24 March 2008

Disgwylfa. Standing on the bwlch between Craig y Pyllauduon and Disgwylfa and looking towards the head of Cwm Teifi. The grassy summit to the right is Disgwylfa, at 459m the highest point in the area: photo by Rudi Winter, 12 January 2008

Craig y Pyllauduon Looking from Craig y Frongoch towards Craig y Pyllauduon across the boggy valley from which the Nant Dderwen originates. Craig y Pyllauduon is probably named after the bog on its side -- the rock of the black pools. However, it's easy to circumnavigate the quagmire: photo by Rudi Winter, 12 January 2008

Berthgoed ridge. The small ridge on the side of this moorland plateau is shown on the 1:25k map as two parallel crags. There are a few rocks sticking out but most of it is covered in the usual grassland. The northern half of the square contains the steep south flank of Cwm Mwyro, the SW corner is part of Strata Florida forest. The remaining high ground is an undulating moorland plateau as shown here: photo by Rudi Winter, 12 April 2007

A view towards Waun Goch and Bryn Daith. Seen here from the south-west boundary of Hafren Forest. A right of way runs across the Waun Goch moorland and beneath the slopes of Esgair y Maesnant (out of view on the right), towards the old Bryn Daith mine: photo by OLU, 8 January 2009

Moorland in the Desert of Wales as seen from the summit of Drygarn Fawr: photo by Velela, 29 March 2009

It was like a church to me.

I entered it on soft foot,

Breath held like a cap in the hand.

It was quiet.

What God there was made himself felt,

Not listened to, in clean colours

That brought a moistening of the eye,

In a movement of the wind over grass

I entered it on soft foot,

Breath held like a cap in the hand.

It was quiet.

What God there was made himself felt,

Not listened to, in clean colours

That brought a moistening of the eye,

In a movement of the wind over grass

There were no prayers said. But stillness

Of the heart’s passions -- that was praise

Enough; and the mind’s cession

Of its kingdom. I walked on,

Simple and poor, while the air crumbled

And broke on me generously as bread.

R. S. Thomas (1913-2000): The Moor, from Pietà, 1966

Tussocks tussocks tussocks. This literally is all there is in this square: tussocks of rough grass, some of it fairly dry (as in the centre of the pic), some more of the reedy sort (as pictured on the left). The land falls off towards the east and south to the source streams of the Afon Tywi. Tussocks!: photo by Rudi Winter, 12 April 2007

Moorland south of Llan Ddu Fawr. The moor climbs steadily towards Llan Ddu Fawr. With a bit of care, the few wet bits can be avoided: photo by Nigel Brown, 12 April 2004

Moorland northeast of Llan Ddu Fawr (2). Looking towards Carnyrhyrddod from near the summit of Llan Ddu Fawr. The peat hags in the middle between the two can be avoided by following an arc to the left. The "Llan" in the name is a corruption of "Lan", short for "Glan", meaning hillside in this context: photo by Nigel Brown, 12 April 2004

Lower slopes of Plynlimon. The track which ends at Llyn Llygad Rheidol passes through typical moorland on the lower slopes west of Plynlimon: photo by Nigel Brown, 2 September 2005

Elenydd moorland west of Pysgotwr, Ceredigion. Beyond the nearby moorland and forest (on Llethr Gwyn) the terrain drops steeply into Cwm Pysgotwr: Photo by Roger Kidd, 13 July 2009

Elenydd landscape south of Llanddewi-Brefi, Ceredigion. Looking across the wide valley of Nant Clywedog-uchaf: photo by Roger Kidd, 18 July 2009

Elenydd Landscape from Carn Penrhiwllwydog, Ceredigion. Across the Doethie valley, the drovers' road climbs from left to right, on its way to Soar-y-Mynydd. To the right of centre, Nant y Benglog plunges down towards the Doethie Fawr. On the skyline to the left is the summit of Drygarn Fawr (height 641 metres -- 2103 feet) 7 miles distant (12.5km): photo by Roger Kidd, 18 September 2007

Elenydd Landscape from Bryn Mawr, Ceredigion. Much of the land here is now designated "open access", which is not to the liking of some landowners on the south side of the Doethie Fawr. Walkers are advised to comply correctly with access regulations in this area: photo by Roger Kidd, 18 September 2007

Edge of Tywi Fechan forest. Looking from the edge of the forest (which is a little north from where the map suggests due to felling) onto the open moorland to the south. The two parallel ridges are Cefn y Cnwc (centre) and Pen y Maen (right/west): photo by Rudi Winter, 24 March 2008

Disgwylfa. Standing on the bwlch between Craig y Pyllauduon and Disgwylfa and looking towards the head of Cwm Teifi. The grassy summit to the right is Disgwylfa, at 459m the highest point in the area: photo by Rudi Winter, 12 January 2008

Craig y Pyllauduon Looking from Craig y Frongoch towards Craig y Pyllauduon across the boggy valley from which the Nant Dderwen originates. Craig y Pyllauduon is probably named after the bog on its side -- the rock of the black pools. However, it's easy to circumnavigate the quagmire: photo by Rudi Winter, 12 January 2008

Berthgoed ridge. The small ridge on the side of this moorland plateau is shown on the 1:25k map as two parallel crags. There are a few rocks sticking out but most of it is covered in the usual grassland. The northern half of the square contains the steep south flank of Cwm Mwyro, the SW corner is part of Strata Florida forest. The remaining high ground is an undulating moorland plateau as shown here: photo by Rudi Winter, 12 April 2007

A view towards Waun Goch and Bryn Daith. Seen here from the south-west boundary of Hafren Forest. A right of way runs across the Waun Goch moorland and beneath the slopes of Esgair y Maesnant (out of view on the right), towards the old Bryn Daith mine: photo by OLU, 8 January 2009

The Drybedd ridge. Looking along the ridge west of the summit of Drybedd.

The pathless ridge fills the NE half of the square, with the Hirnant

valley taking up the opposite corner. All of this is wild moorland used,

if at all, for rough grazing. The Nant y Moch dam can be seen on the right in the distance: photo by Rudi Winter, 1 April 2007

Above Gwar-Cwm: photo by Chris Denny, 26 October 2008

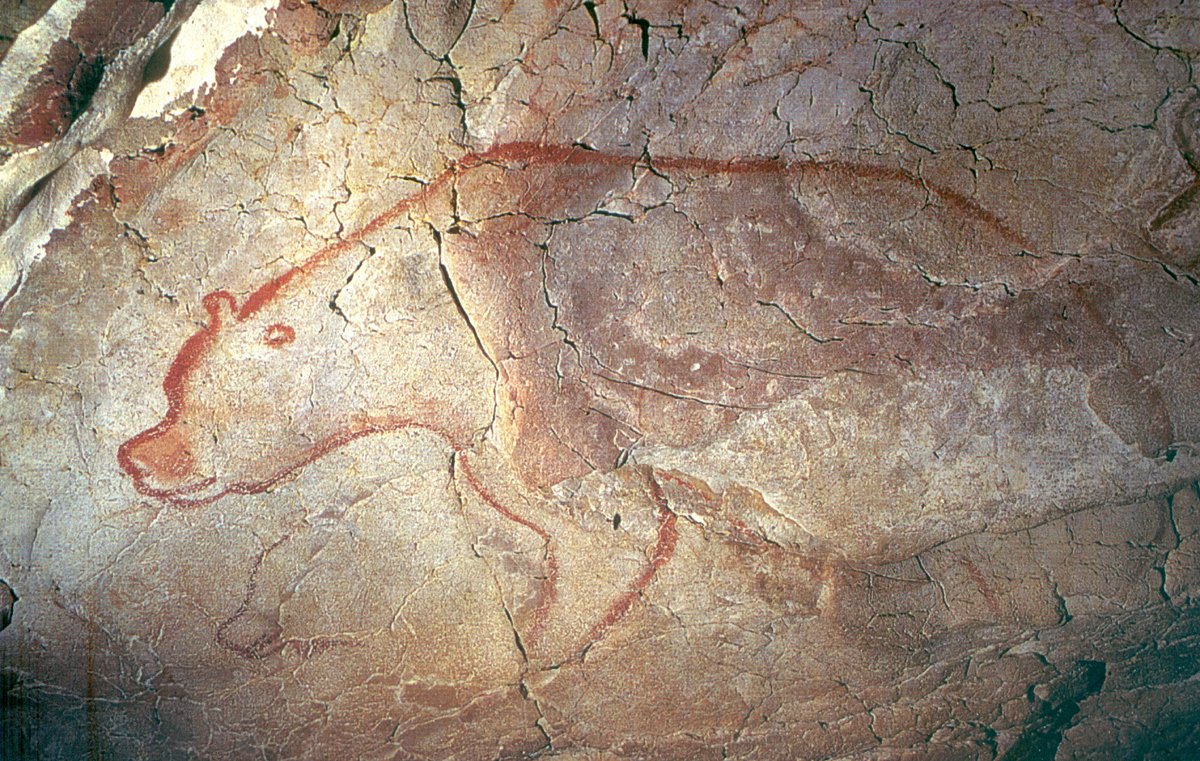

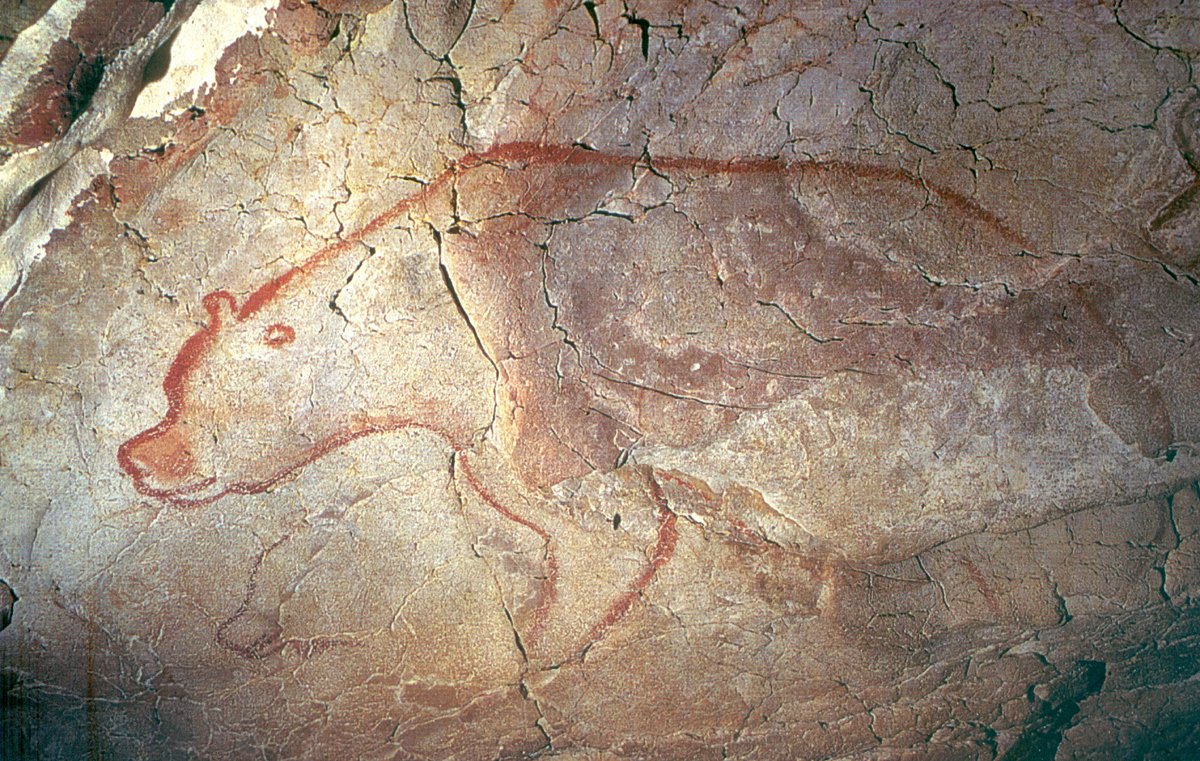

The wonderfully enigmatic painted red mammoth of El Pindal Cave on the northern coast of Spain #IceAgeArt. Is that a heart or a wound?: image via The Ice Age @Jamie_Woodward_, 19 March 2017

TwilightBeasts@TwilightBeasts

Robert Macfarlane Retweeted TwilightBeasts

Robert Macfarlane added,

"polished to a reflective shine by the rubbing of thousands of cave bears over tens of thousands of years...". More on bärenschliffe here!

tweet via Robert Macfarlane @RobGMacfarlane, 14 March 2017

#IceAge word of the day: "Bärenschliffe" - polished rock surfaces in caves worn smooth by the passage of bears @RobertGMacfarlane: image via The Ice Age @jamie_woodward_, 13 March 2017

One of the Chauvet horses coloured a brilliant orange by a band of natural iron oxide staining #IceAgeArt: image via The Ice Age @jamie_woodward_, 13 March 2017

DSC09943-2: photo by noppadol maitreechit, 17 March 2017

DSC09943-2: photo by noppadol maitreechit, 17 March 2017

DSC09943-2: photo by noppadol maitreechit, 17 March 2017

DSC_4563 Purim tish Bnei Brak 2016: photo by ilan Ben yehuda, 26 March 2016

DSC_4563 Purim tish Bnei Brak 2016: photo by ilan Ben yehuda, 26 March 2016

DSC_4563 Purim tish Bnei Brak 2016: photo by ilan Ben yehuda, 26 March 2016

High radioactivity [Tours, France]: photo by François Tomasi, March 2017

High radioactivity [Tours, France]: photo by François Tomasi, March 2017

High radioactivity [Tours, France]: photo by François Tomasi, March 2017

R0252891: photo by Tyler Simpson, 2 March 2013

R0252891: photo by Tyler Simpson, 2 March 2013

R0252891: photo by Tyler Simpson, 2 March 2013R0252891: photo by Tyler Simpson, 2 March 2013

Is that a heart or a wound?

The wonderfully enigmatic painted red mammoth of El Pindal Cave on the northern coast of Spain #IceAgeArt. Is that a heart or a wound?: image via The Ice Age @Jamie_Woodward_, 19 March 2017

TwilightBeasts@TwilightBeasts

Robert Macfarlane added,

"polished to a reflective shine by the rubbing of thousands of cave bears over tens of thousands of years...". More on bärenschliffe here!

tweet via Robert Macfarlane @RobGMacfarlane, 14 March 2017

#IceAge word of the day: "Bärenschliffe" - polished rock surfaces in caves worn smooth by the passage of bears @RobertGMacfarlane: image via The Ice Age @jamie_woodward_, 13 March 2017

The bear necessities

Ursus spelaeus [reconstruction]: image via serchio25, 2008

The Cave Bear was a very big species of bear!: image by Jan Freedman

Anthropocene signs and omens: bioluminescence off Tasmanian coast as a climate-change indicator.: image via Robert Macfarlane @RobGMacfarlane, 15 March 2017

Humans and bears have a strange relationship. On the one hand we see

them as lovable, smart, curious creatures (think Baloo from the Jungle

Book). On the other, we have taken great pains to exterminate them

wherever and whenever we could. Thankfully, no bear species has gone

extinct for over 10,000 years (although many subspecies have been lost).

During the Pleistocene, the old world was home to a complex of species

that may have been amongst the biggest of bears. The cave bear (Ursus spelaeus)

was perhaps the first Twilight Beast to be studied in a scientific

sense, thanks to the millions of bones the animal left behind in caves

throughout Europe and Asia, the legacy of many individuals who failed to

survive hibernation. Thought to have inspired legends of dragons that

lived in caves, the bones were so numerous that they were occasionally

mined as a source of phosphate. Named way back in the 18th century by Johann Christian Rosenmüller, the cave bear has been at the forefront of Pleistocene research ever

since. This vanguard position continues into the present day: Ursus spelaeus

was the first extinct mammal to have its nuclear genome sequenced. The

oldest mitochondrial genome we have is that of a Middle Pleistocene cave

bear (and it was used to test methods that were later utilised to

sequence DNA from Homo heidelbergensis).

The Cave Bear was a very big species of bear!: image by Jan Freedman

The cave bear (along with other “species” within the complex such as Ursus ingressus, Ursus deningeri) was a huge animal. Larger than the largest Kodiak brown bears (Ursus arctos),

this imposing creature was probably a strict vegetarian rather than an

omnivore. Analysis of teeth micro-abrasions and the stable isotopes that

were incorporated into the bones show that these were gentle giants

(although, giant herbivores are not to be underestimated, as anyone who

lives around hippos or elephants will tell you). They may have been one

of the main prey of another Pleistocene predator, the cave lion (Panthera spelaea). One can imagine a stealthy lion, winding through the winter caves, picking off the hibernating bears.

We still find traces of the lifestyle of the vanished cave bear within European caves. Many caves, including the famous Chauvet,

still have visible marks from where the animal sharpened their claws on

the walls. In some cases Palaeolithic people incorporated the marks

into their art. Some caves (e.g. Große Klingerberg Höhle in Bavaria)

have circular depressions visible in the cave floor, which have been

interpreted as bear nests, caused by the animal turning in its sleep

while hibernating. Speleologists have even recovered kidney stones from

amongst the skeletons of cave bears.

Examples of cave bear trace fossils from the Ursilor cave in Romania. Top: footprints, Middle: clawmarks, Bottom: hibernation nests.: images ©Cajus Diedrich

Perhaps the most evocative sign left by the cave bear, which speaks

of how integral the species once was to the European ecosystem, and how

long it was a part of it, is something known as Bärenschliffe. Simply

put, this is stone found in narrow cave routes that has been polished to

a reflective shine by the scratching and rubbing of thousands of cave

bears over tens of thousands of years.

Within these caves, the bears would have occasionally encountered another apex predator (Homo sapiens, Homo neanderthalensis).

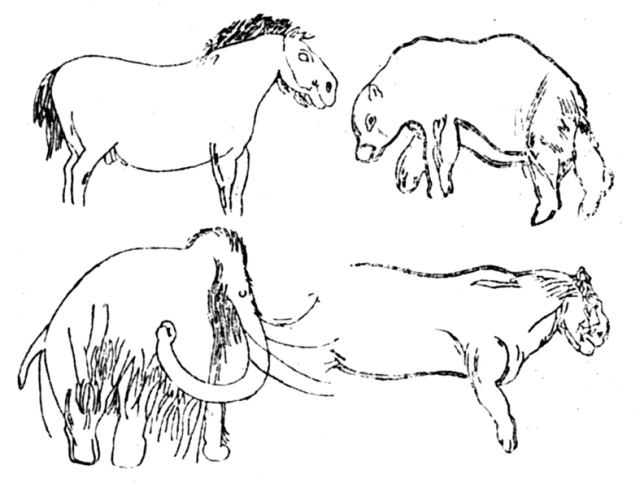

There are a few images within cave art that may be of the cave bear.

Separating the paintings of brown bears and cave bears can be difficult

but there are some morphological differences that can point us in the

right direction. Compared to brown bears, cave bears have a huge

protruding forehead, which is sometimes noticeable in cave art.

Top: The distinctive skull of Ursus spelaeus: image by Didier Descouens via Wikimedia Commons

Bottom: Public domain image of art from Les Combarelles cave, showing a bear (top right) with the distinctive forehead of Ursus spelaeus

The last cave bears probably died about 27000 calendar years ago,

much earlier than the extinction of mammoth, woolly rhino, or cave lion.

Genetic evidence suggests that this extinction occurred after a

prolonged period of genetic bottlenecking. The cause is likely to have

been a combination of change in climate affecting the nutritious

vegetation the cave bear needed as well as an increase in pressure from

Palaeolithic humans for cave sites.

Written by Ross Barnett (@DeepFriedDNA)

The bear necessities via Twilight Beasts @twilightbeasts, 2 July 2014

Anthropocene signs and omens: bioluminescence off Tasmanian coast as a climate-change indicator.: image via Robert Macfarlane @RobGMacfarlane, 15 March 2017

Word of the day: "gall-shíon" - 'severe weather, as if it blew from a strange country' (Irish). Ty Carol Anne-Connolly.: image via Robert Macfarlane @RobGMacfarlane,

14 March 2017

'as if it blew from a strange country'

Weird purplish clouds massing offshore to the west again tonight real spooky

over the refinery corridor

Maybe the Old People

the ancient indigenes

poised at the dark stygian bank

of yet another ominous looking atmospheric river

would have been able to figure all this out by magical thinking

The strange weather

probably wouldn't have seemed so strange to them

if they'd seen it from the black gulf of the mayhem freeway its birth-maw

The freeway on the other hand would have seemed very strange to them

First thought: Get back to cave now!

One of the Chauvet horses coloured a brilliant orange by a band of natural iron oxide staining #IceAgeArt: image via The Ice Age @jamie_woodward_, 13 March 2017

Sanctus Spiritus

DSC09943-2: photo by noppadol maitreechit, 17 March 2017

DSC09943-2: photo by noppadol maitreechit, 17 March 2017

DSC09943-2: photo by noppadol maitreechit, 17 March 2017

DSC_4563 Purim tish Bnei Brak 2016: photo by ilan Ben yehuda, 26 March 2016

DSC_4563 Purim tish Bnei Brak 2016: photo by ilan Ben yehuda, 26 March 2016

DSC_4563 Purim tish Bnei Brak 2016: photo by ilan Ben yehuda, 26 March 2016

High radioactivity [Tours, France]: photo by François Tomasi, March 2017

High radioactivity [Tours, France]: photo by François Tomasi, March 2017

High radioactivity [Tours, France]: photo by François Tomasi, March 2017

R0252891: photo by Tyler Simpson, 2 March 2013

R0252891: photo by Tyler Simpson, 2 March 2013

R0252891: photo by Tyler Simpson, 2 March 2013R0252891: photo by Tyler Simpson, 2 March 2013

Sanctus Spiritus Cuba 2016: photo by Spiros Soueref, 11 December 2016

2 comments:

Tom,

thought you might like this (if you haven't already read it):

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2002/oct/12/art.artsfeatures3

Thank you, billoo.

"The need for companionship while alive was the same. The Cro-Magnon reply, however, to the first and perennial human question, "Where are we?" was different from ours. The nomads were acutely aware of being a minority overwhelmingly outnumbered by animals. They had been born, not on to a planet, but into animal life. They were not animal keepers: animals were the keepers of the world and of the universe around them, which never stopped. Beyond every horizon were more animals.

"At the same time, they were distinct from animals. They could make fire and therefore had light in the darkness. They could kill at a distance. They fashioned many things with their hands. They made tents for themselves, held up by mammoth bones. They spoke. (So, perhaps, did animals.) They could count. They could carry water. They died differently. Their exemption from animals was possible because they were a minority, and, being a minority, the animals could pardon them for this exemption."

Post a Comment