Day

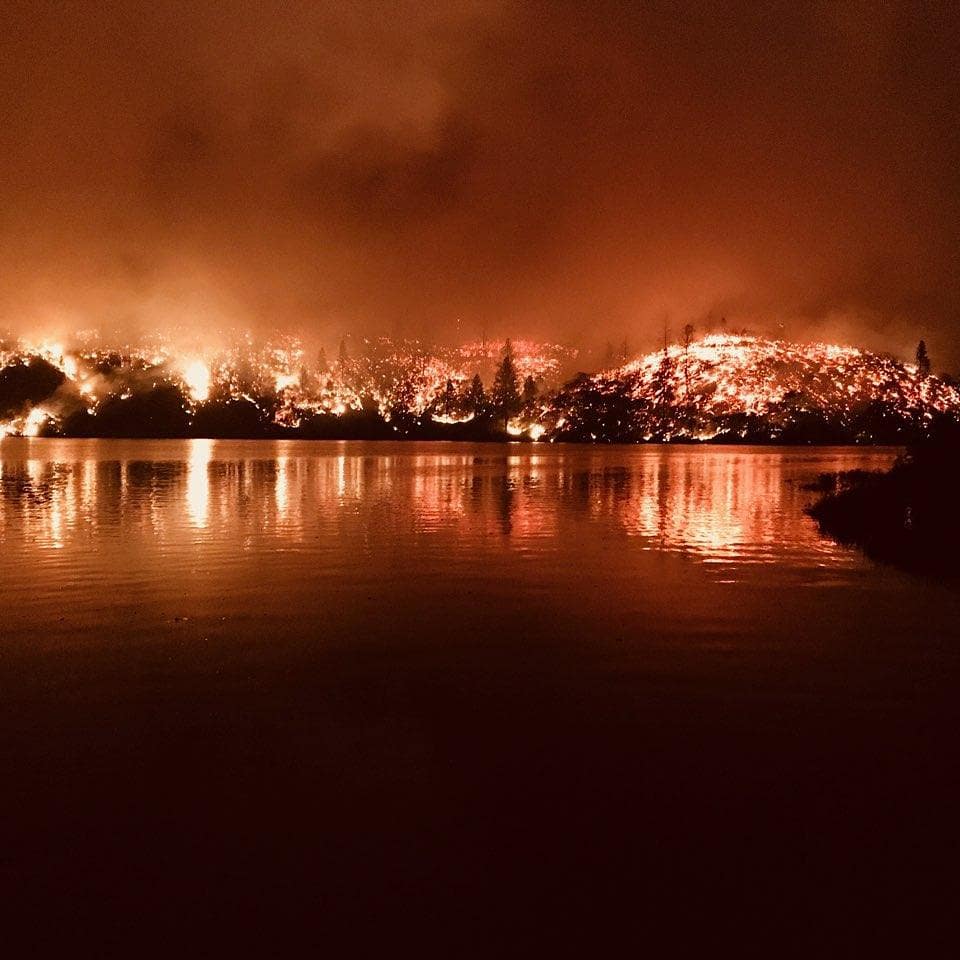

three of the #carrfire - #firefighters are working hard to contain the

out of control blaze that has consumed over 80,000 acres, destroyed over

500 structures and stands at 5% containment. 5 deaths have been

confirmed including 2 firefighters #redding: image via Justin Sullivan @sullyfoto, 28 July 2018

Smoke and haze from #carrfire cause a strange color cast and the withered trees help form such a desolate landscape: image via Marcus Yam @yamphoto, 28 July 2018

#CarrFire [update] off Hwy 299 and Carr Powerhouse Rd, Whiskeytown (Shasta

County) is now 48,312 acres and 5% contained. NEW MANDATORY EVACUATION

ORDERS IN PLACE. Unified Command: @CALFIRESHU and Whiskeytown National Park.: image via CAL FIREVerifiedaccount@CAL_FIRE, 27 July 2018

Mark Peterson, who lost his home in the Carr Fire, gives water to goats that survived the blaze.: photo by Noah Berger/AP 27 July 2018

Update: 5 dead, including 2 children, as #CarrFire continues to burn: image via Marcus Yam @yamphoto, 28 July 2018

Update: 5 dead, including 2 children, as #CarrFire continues to burn: image via Marcus Yam @yamphoto, 28 July 2018

Update: 5 dead, including 2 children, as #CarrFire continues to burn: image via Marcus Yam @yamphoto, 28 July 2018

Update: 5 dead, including 2 children, as #CarrFire continues to burn: image via Marcus Yam @yamphoto, 28 July 2018

Day three of the #carrfire - #firefighters are working hard to contain the out of control blaze that has consumed over 80,000 acres, destroyed over 500 structures and stands at 5% containment. 5 deaths have been confirmed including 2 firefighters #redding: image via Justin Sullivan @sullyfoto, 28 July 2018

Day

three of the #carrfire - #firefighters are working hard to contain the

out of control blaze that has consumed over 80,000 acres, destroyed over

500 structures and stands at 5% containment. 5 deaths have been

confirmed including 2 firefighters #redding: image via Justin Sullivan @sullyfoto, 28 July 2018

Day

three of the #carrfire - #firefighters are working hard to contain the

out of control blaze that has consumed over 80,000 acres, destroyed over

500 structures and stands at 5% containment. 5 deaths have been

confirmed including 2 firefighters #redding: image via Justin Sullivan @sullyfoto, 28 July 2018

A firefighter lights backfires during the Carr fire in Redding, California.: photo by Josh Edelson/AFP/Getty Images, 27 July 2018

Villagers evacuate after a hydropower dam collapsed in Laos: image via Reuters Pictures@reuterspictures, 27 July 2018

#Japan Disaster-hit Japan braces for powerful typhoon Photo @MartinBureau1 #AFP: image via AFP Photo @AFPphoto, 28 July 2018

#BloodMoonEclipse Photo @ArisMessinis: image via Getty Images News @Getty Images News, 27 July 2018

#Japan Disaster-hit Japan braces for powerful typhoon Photo @MartinBureau1 #AFP: image via AFP Photo @AFPphoto, 28 July 2018

#BloodMoonEclipse Photo @ArisMessinis: image via Getty Images News @Getty Images News, 27 July 2018

They

They

They didn't know what to say yesterday

They'll show up for the show

Just don't expect them to say anything

Or not expect everything they don't yet have

To come to them because they're them

Nobody told them they'd ever have to say anything

They secretly think being them is perfect

They secretly think being them is perfect

Although they can't say this

Because they can't say anything

Returning militias, Managua, Nicaragua, 1982: photo by Marcelo Montecino, 26 March 2014

Family of Disappeared, Managua, Nicaragua, 78: photo by Marcelo Montecino, 28 August 2014

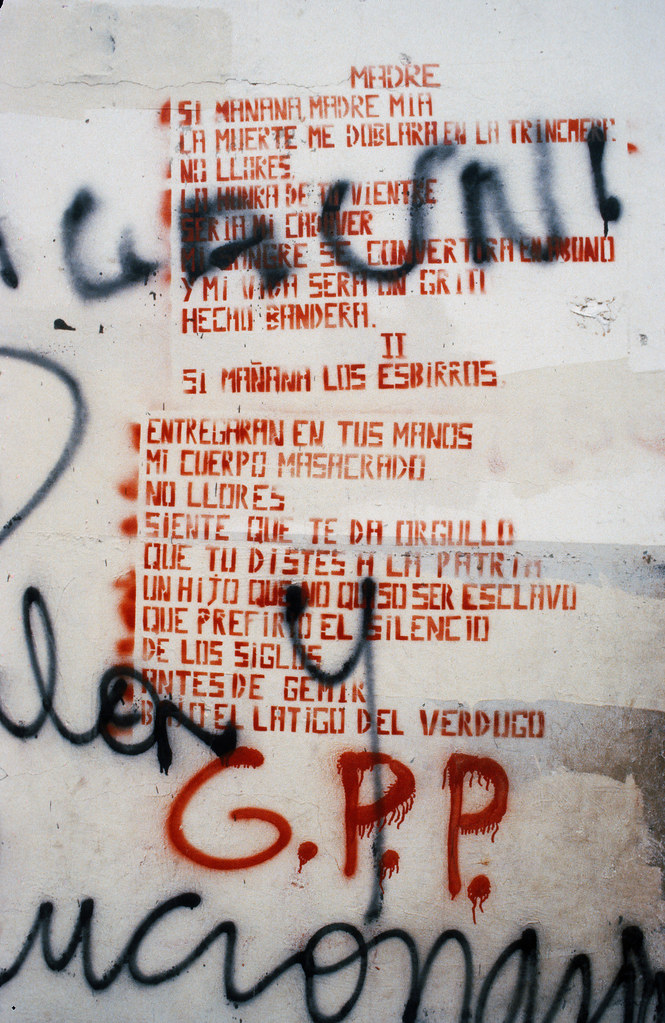

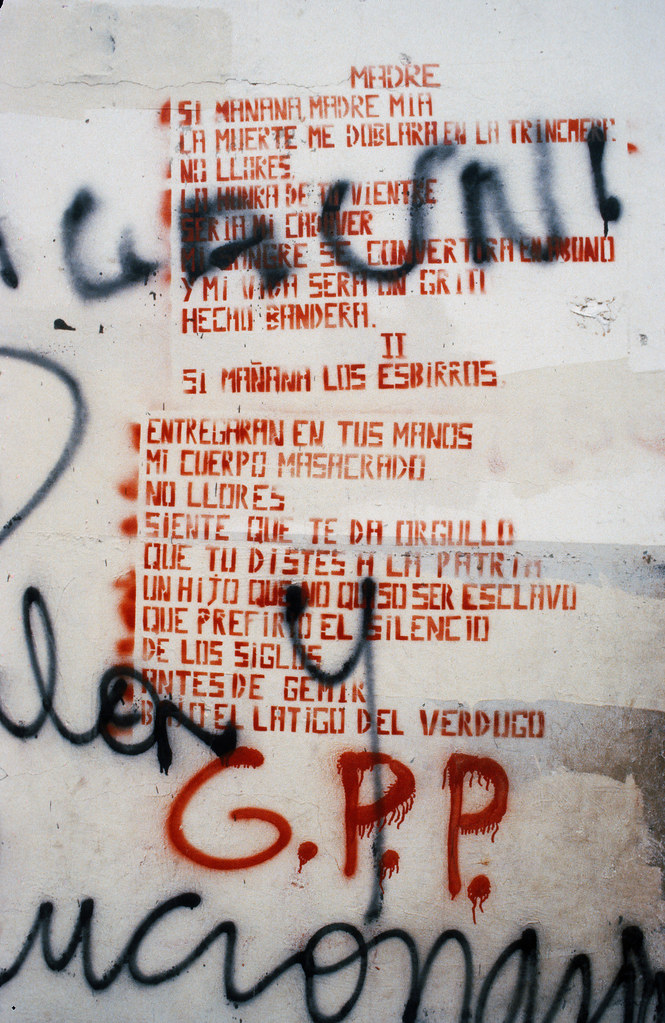

Madre, Managua, Nicaragua 78: photo by Marcelo Montecino, 25 October 2014

si mañana los esbirros

entregaran en tus manos

mi cuerpo masacrado

no llores

siente que te da orgullo

que tu distes a la patria

un hijo que no quiso ser esclavo

que prefirio el silencio de los siglos

antes de gemir bajo el latigo del verdugo.

- transcription Jairo Leiva

Returning from Fighting Contras, Managua, Nicaragua, 82: photo by Marcelo Montecino, 2 April 2017

Family of Disappeared, Managua, Nicaragua, 78: photo by Marcelo Montecino, 28 August 2014

Madre, Managua, Nicaragua 78: photo by Marcelo Montecino, 25 October 2014

Madre

si mañana madre mia

la muerte me doblara en la trinchera

no llores

la honra de tu vientre

seria mi cadaver

mi sangre se convertira en abono

y mi vida sera un grito

hecho bandera

la muerte me doblara en la trinchera

no llores

la honra de tu vientre

seria mi cadaver

mi sangre se convertira en abono

y mi vida sera un grito

hecho bandera

II

si mañana los esbirros

entregaran en tus manos

mi cuerpo masacrado

no llores

siente que te da orgullo

que tu distes a la patria

un hijo que no quiso ser esclavo

que prefirio el silencio de los siglos

antes de gemir bajo el latigo del verdugo.

-G.P.P

- transcription Jairo Leiva

Este poema fue musicalizado

por el Grupo Pueblo y el grupo Libertad en los años de la Revolución. El

héroe y mártir Leonel Cruz Estrada, caído en 1979 la operación

Astronauta en el km 11 de la carretera a Masaya, compuso este poema

- santiago009

Returning from Fighting Contras, Managua, Nicaragua, 82: photo by Marcelo Montecino, 2 April 2017

Dole Banana Plantation, Nicaragua, 79: photo by Marcelo Montecino, 4 December 2013

Militias, Managua, Nica 83: photo by Marcelo Montecino, 3 March 2017

Return from the Front, Managua, Nicaragua, 1982: photo by Marcelo Montecino, 4 August 2013

Somoza Forever, Leon, Nicaragua, 1984: photo by Marcelo Montecino, 12 July 2016

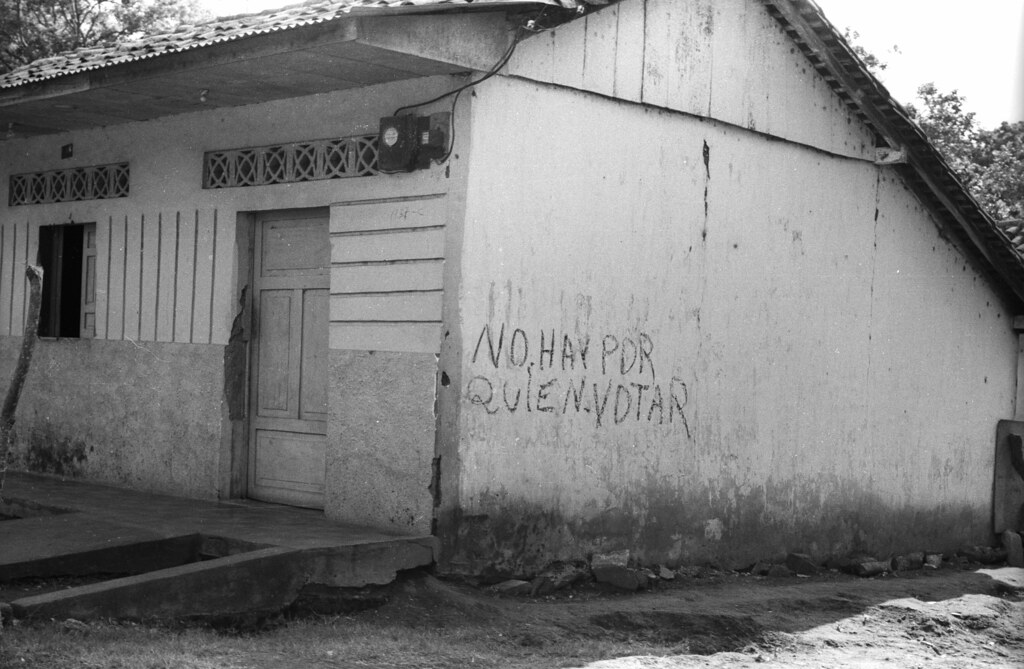

Poneloya, Nicaragua, 75 | The wall reads: "There's no one to vote for.": photo by Marcelo Montecino, 3 December 2014

Morning in Masaya, Nicaragua: photo by Marcelo Montecino, 28 August 2014

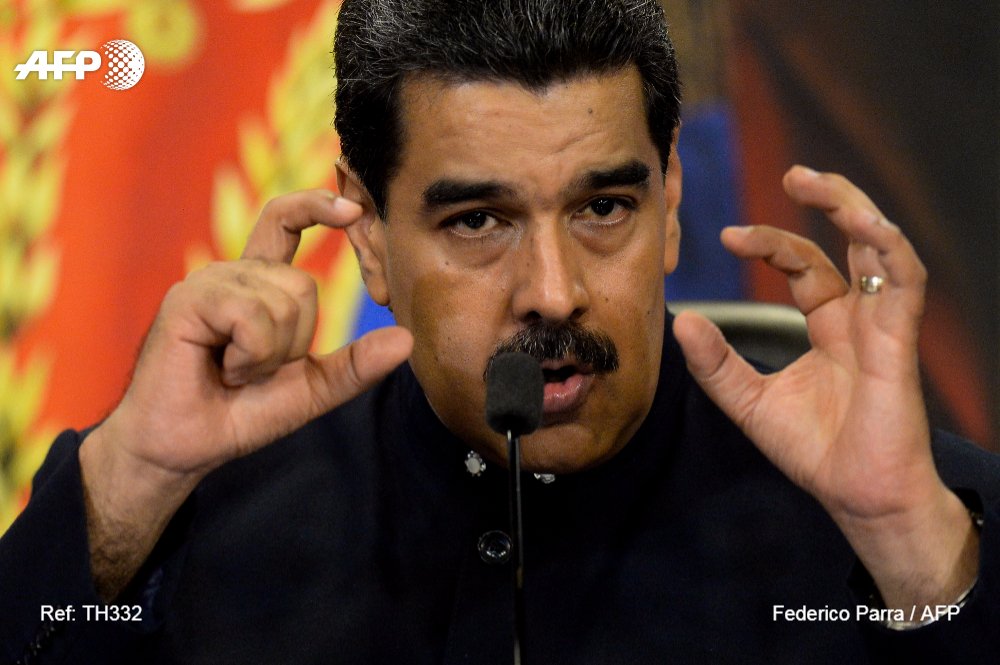

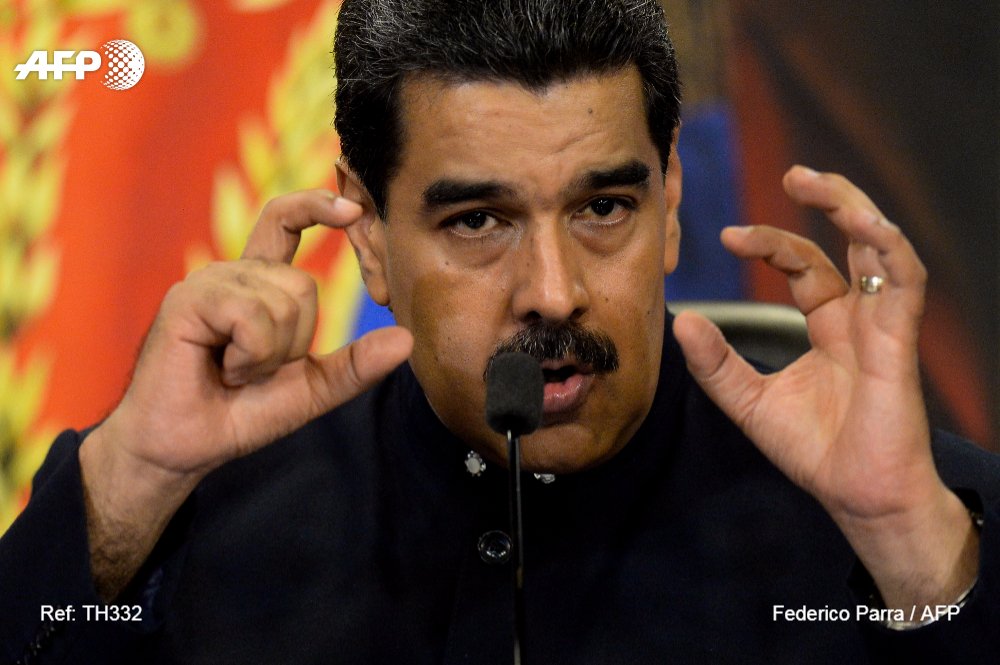

EEUU podría considerar sanciones económicas a Nicaragua, dice su secretario del Tesoro, Steven Mnuchin. #AFP: image via Agence France-Presse @AFPespanol, 21 July 2018

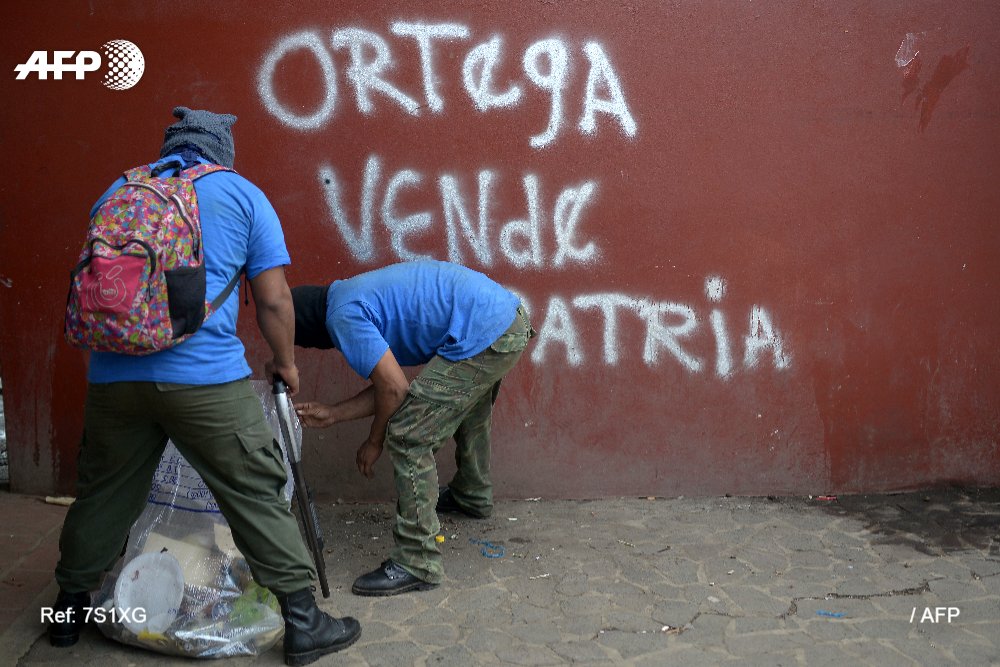

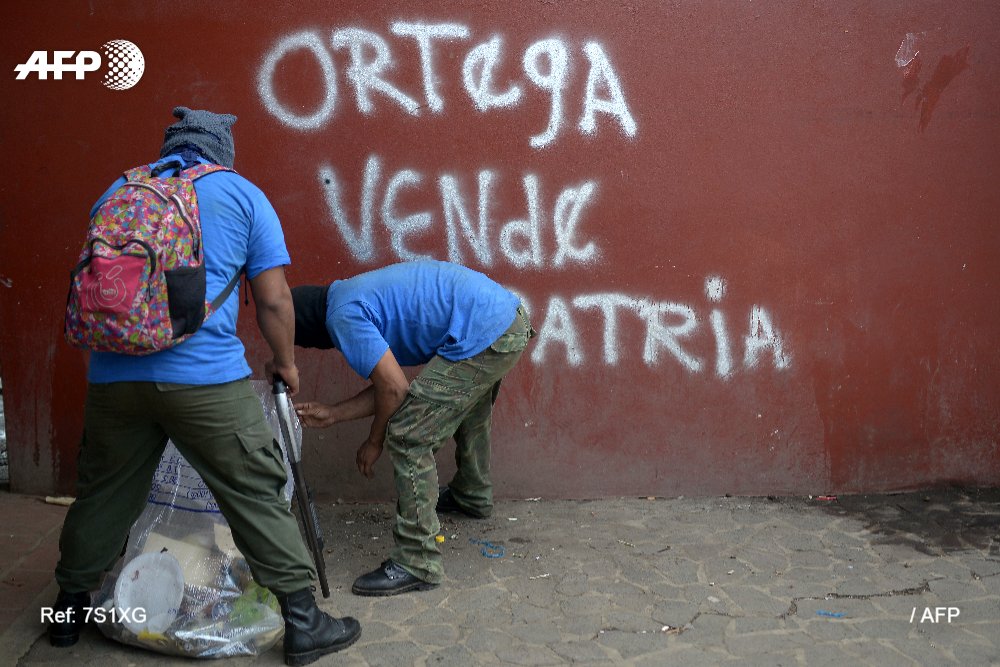

Nicaragua-Venezuela: 5 ressemblances et différences de la crise Photo @AFPphoto #AFP: image via Tupac Pointu @tpointu, 20 July 2018

Nicaragua-Venezuela: 5 ressemblances et différences de la crise Photo @AFPphoto #AFP: image via Tupac Pointu @tpointu, 20 July 2018

Nicaragua-Venezuela: 5 ressemblances et différences de la crise Photo @AFPphoto #AFP: image via Tupac Pointu @tpointu, 20 July 2018

Gobierno de Nicaragua controla feudo opositor tras operativo que dejó dos muertos #AFP: image via Agence France-Presse @AFPespanol, 21 July 2018

Managua -- When I was asked to go to Nicaragua, I didn’t hesitate for a second. I wanted to cover the critical situation that was happening there since April and not just read about it – or, more accurately, suffer – from the close-but-not-so-close vantage point of Venezuela. It was a situation that was “worse than the war” the country went through in the 1980s, according to residents.

Nicaragua-Venezuela: 5 ressemblances et différences de la crise Photo @AFPphoto #AFP: image via Tupac Pointu @tpointu, 20 July 2018

Nicaragua-Venezuela: 5 ressemblances et différences de la crise Photo @AFPphoto #AFP: image via Tupac Pointu @tpointu, 20 July 2018

Nicaragua-Venezuela: 5 ressemblances et différences de la crise Photo @AFPphoto #AFP: image via Tupac Pointu @tpointu, 20 July 2018

Gobierno de Nicaragua controla feudo opositor tras operativo que dejó dos muertos #AFP: image via Agence France-Presse @AFPespanol, 21 July 2018

Nicaragua: Worse than the war: Maria Isabel Sanchez, AFP Correspondent, Friday 27 July 2018

Managua -- When I was asked to go to Nicaragua, I didn’t hesitate for a second. I wanted to cover the critical situation that was happening there since April and not just read about it – or, more accurately, suffer – from the close-but-not-so-close vantage point of Venezuela. It was a situation that was “worse than the war” the country went through in the 1980s, according to residents.

In 25 years of working at AFP I have

encountered extreme, risky and complicated moments in various Latin

American countries. A year ago, with the team in Caracas, I covered four long and exhausting months of demonstrations in Venezuela. But this time it was different. Nicaragua is the country where I was born.

Paramilitaries are seen on trucks at Monimbo neighborhood in Masaya, Nicaragua, on July 18, 2018, following clashes with anti-government demonstrators.: photo by AFP, 18 July 2018

Along its roads, at intersections, next to

traffic lights and pedestrian crossings, and crammed in the back of

four-door pick-up trucks, the sight of civilians masked and heavily

armed greeted my return to Nicaragua’s capital.

Just after arriving at the hotel, my photo

and video colleagues and myself headed off to Masaya, a city that

historically has always been the most rebellious in the country. In a

small, modest cemetery three protesters were being buried. They had been

killed by the pro-government forces of President Daniel Ortega while

they manned barricades.

A friend of Jorge Carrion, 33, who was shot dead during protests against the government of President Daniel Ortega, carries a homemade mortar and shouts anti-government slogans during Carrion's funeral in the city of Masaya, 35 km from Managua on June 7.: photo by AFP, 7 June 2018

Friends and relatives cry during the funeral of Jorge Carrion, 33, shot dead during protests against the government of President Daniel Ortega, in the city of Masaya, 35 km from Managua on June 7, 2018.: photo by AFP, 7 June 2018

A blue and white Nicaraguan flag

covered one of the wooden coffins, which lay at the bottom of a

two-meter deep grave. Two men shoveled dirt onto it. Looking around at

the mourners, I saw faces contracted by tears, impotence and rage.

A demonstrator stands inside a bus set alight during a day-long national strike held to mark two months of violent chaos under President Daniel Ortega, in Tipitapa, about 25 km from Managua on June 14, 2018.: photo by AFP, 14 June 2018

Each day I spent in Nicaragua was a challenge, professionally and personally. The violence had swelled beyond the limits of anti-government demonstrations:

deaths and gunfire occurred daily, houses were torched – one with an

entire family inside, children and adolescents hit by bullets,

disappearances, persecution, harassment.

Tear gas, used almost daily in Venezuela

during protests, was used only for a few days in Nicaragua. After, it

was bullets that were fired.

A riot police officer fires a weapon during clashes with students taking part in a protest in Managua on May 28, 2018.: photo by AFP, 28 May 2018

Just like it was at war, the

government launched an intense operation combining police, anti-riot

forces and paramilitary groups to “liberate” and “retake” territory in

Masaya, tearing down to the last the hundreds of road barricades of

loose paving stones that had been built in a sign of resistance and as a

way of protecting local residents.

Friends and relatives carry the coffin of Jose Esteban Sevilla Medina, who was shot dead during clashes with riot police and paramilitaries at Monimbo neighbourhood in Masaya, some 35 km from Managua, on July 16, 2018.: photo by AFP, 16 July 2018

Wearing masks, the paramilitaries go about

their business wearing the same-color t-shirts: white one day,

sometimes green, other times grey or blue, so they don’t get mistaken

for the protesters on the roadblocks. The latter are also masked, so

they aren’t identified by the police and especially any neighbors loyal

to Ortega. For the government, they are all “terrorists.”

For our own security, we try to go

to the zones of conflict only after a clash has happened, and always in

a convoy with colleagues from other media. Despite that, sometimes we

get caught in the crossfire of bullets or homemade mortars, as happened

one day in Masaya, in the flashpoint neighborhood of Monimbo. According

to locals, there was an elite sniper on one of the roofs.

An anti-government demonstrator fires a home-made mortar during clashes with riot police at a barricade in the town of Masaya, 35 km from Managua on June 9, 2018.: photo by AFP. 9 June 2018

In this district of indigenous craftsmen, I

interviewed a mathematics physics professor. He was a child when a

popular uprising in 1979 toppled the dictator Anastasio Somoza. As a

young man in the mid-1980s he fought to defend the revolution in the

mountains where he lost a leg.

But nothing could console him over the

death of his son in April this year, found in a trench. We spoke for a

long time through an afternoon. After, we remained in contact. He kept

me up to speed when anti-riot units and paramilitary forces approached

with the aim of taking Monimbo.

Anti-government demonstrators remain at an improvised barricade in the town of Masaya, 35 km from Managua on June 5, 2018.: photo by AFP, 5 June 2018

With a bullet-proof jacket and a helmet

making movement difficult, we walked kilometers between the barricades

of paving stones to enter villages to find witnesses of what had

happened there.

In Sutiaba, an indigenous part of Leon, a

city 90 kilometers northwest of Managua, we arrived early in the

morning. We left the vehicles on the outskirts of the city and walked

toward the center, guided by local colleagues who helped us avoid the

routes controlled by police and paramilitaries. Before leaving, one of

our guides closed his eyes, lowered his head and prayed.

The few residents we found in the streets

of the town, which otherwise seemed deserted, pointed us to houses

where, the day before, something had happened as pro-governmental forces

had violently invaded. We knocked on the door of one of them and a

women opened it to us. In front of us, just a meter and a half away,

there was a body covered with a white sheet lying on a bed. On one side,

a small bloodstain was barely visible.

A supporter of Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega takes part in a pro-FSLN government rally on Nicaragua's National Mothers Day at the Rotonda Hugo Chavez in Managua on May 30, 2018. : photo by AFP, 30 May 2018

The most difficult moment is one

when a decision needs to be made. To take the risk or not to go to where

conflict is happening. In Diriamba, 40 kilometers southwest of Managua,

we arrived early in the morning with other international journalists in

three vehicles, a day after the government’s forces. According to human

rights groups, more than a dozen people had been killed in the

operation there.

Paramilitaries surround the San Sebastian Basilica, in Diriamba, Nicaragua on July 09, 2018. Armed supporters of the government of Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega burst into the basilica, besieged and insulted bishops who had earlier arrived in Diriamba.: photo by AFP, 9 July 2018

Coming around the corner of a street, we

found ourselves in front of the basilica, next to which there were

around 50 paramilitaries. Inside the church, a dozen people had taken

refuge in the priest’s quarters after escaping gunfire the day before.

Two flags of Ortega’s Sandinista National Liberation Front had been

hoisted atop the town’s clock tower.

Unable to turn back, we continued on our

way, projecting calmness and keeping an eye in the rearview mirror to

see if we were followed. A few streets on, we stopped and, after

discussing it, decided to go back. We first went up to speak to two

women in the group of paramilitaries, thinking it would be easier.

Paramilitaries rest in Monimbo neighborhood in Masaya, Nicaragua, on July 18, 2018, following clashes with anti-government demonstrators. The head of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has described as "alarming" the ongoing violence in Nicaragua.: photo by AFP, 18 July 2018

Once we convinced the masked men that we

simply wanted to know their version of what happened, we called the rest

of our colleagues.

In their interviews, the paramilitaries declared that they didn’t have weapons and were simply residents who had organized themselves against the protesters to “liberate” the people. Several locals supporting them came up. Mid-morning, there were around 100 of them when a delegation of bishops arrived to provide assistance to the residents holed up in the basilica.

Yelling a slew of insults, the government

supporters surrounded the clergymen and pushed their way into the church

by force when the doors were opened to let the bishops and journalists

pass. Chaos followed. Suddenly, between shoves and blows, we saw masked

men, some armed, force their way in looking for those taking refuge.

Paramilitaries burst into the San Sebastian Basilica, in Diriamba, Nicaragua on July 09, 2018. Supporters of the government of Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega besieged and insulted bishops who had earlier arrived in Diriamba: photo by AFP, 9 July 2018

A woman afraid of pro-government Sandinista youths embraces a nun as she takes shelter at the San Sebastian Basilica in Diriamba, Nicaragua, on July 9, 2018. Hundreds of under-pressure Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega supporters broke into the basilica.: photo by AFP, 9 July 2018

At the altar, two paramilitaries saw

me taking photos with my cellphone and turned on me. After an argument

one of them snatched my phone.

I followed him and grabbed

it back. That enraged him and he fiercely shoved me. Forcing myself to

stay calm, I persuaded him to let me delete the photos. Once that was

done he allowed me to leave the church.

In the melee, colleagues managed to

find each other and we exchanged our respective experiences: our

photographer Marvin Recinos was beaten on the arm by one masked man who

stole his camera; one journalist from a local TV station had his nose

broken and his equipment also stolen; the paramilitaries had also aimed

their weapons at a cameraman from an international news channel.

We quickly left Diriamba, shaken and conscious that it could have turned out worse.

A Managua, des paysans ont passé la nuit dans une église après des affrontements mortels la veille ayant suivi une marche dans la capitale. 31 mai 2018.: photo by AFP 31 May 2018

Several times I found

myself at a loss to see how little the rest of the world was paying

attention to what was unfolding in this poor little Central American

country.

With a history marked by military

invasions, civil wars and natural disasters, it seems to have forged its own

character through suffering.

Coming from Venezuela, a country often on

the front pages of the international press with the turmoil of its

never-ending crisis, I was stunned that the situation in Nicaragua

attracts less of the world’s interest, even though it was bloodier.

For journalists, it’s also much more

dangerous. We never went out at night. Managua and other cities in the

country were under a curfew imposed for months. From 6pm, the streets of

the towns and cities were deserted. Many businesses were shuttered and

nightlife was dead.

Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega (R) and his wife, Vice President Rosario Murillo, cheer at supporters during the government-called Walk for Security and Peace in Managua on July 7, 2018.: photo by AFP, 7 July 2018

As in Venezuela, official sources of

information were unavailable. A request for an interview with the

president was politely refused by his wife Rosario Murillo, who is also

his vice president and the government’s chief spokesperson.

The international media was also accused

by the government of waging a disinformation campaign and to facilitate a

“coup d’état,” which put us at risk when we covered pro-governmental

demonstrations. But, so far, correspondents sent to the country have had

no problem getting in.

A municipal worker sweeps the floor in front of a mural depicting Cuban revolutionary leader Fidel Castro (L) and Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega at Cuba square in Managua on November 26, 2016, the day after Castro died.: photo by AFP, 26 November 2016

For the month I was in Nicaragua, I often

heard the refrain “it’s worse than the war,” referring to the conflict

the country saw with the Sandinista revolution and the subsequent battle

against Contra rebels backed by the US. It was said because of the

impotence residents felt, not because of fear. They were displaying

admirable courage, like that that I saw in Monimbo.

I finished my assignment in Nicaragua a

day after an attack on students at the National Autonomous University

who had been at the forefront of protests, and on a nearby church where,

between raking gunfire, they had taken refuge for a night.

That Sunday, as I traveled out of the country, a government operation began to “retake” the rebel district of Monimbo.

A woman looks back after passing by a barricade in the neighbourhood of Monimbo, in Masaya, a city some 35 km from Managua, on May 21, 2018: photo by AFP, 21 May 2018

"They aren’t attacking. We have people

wounded and we can’t evacuate them. They have us surrounded," the

professor told me on WhatsApp.

It was the last message I received from

him. I later saw on social media a photo of him next to a little shrine

with an image of his son between white and yellow flowers.

“Urgent,

urgent! The professor has been kidnapped,” read the caption, and since

then I’ve had no news about him.

View of the headquarters of the FSLN which were occupied and looted by a mob of protesters in Diriamba, 40 km from Managua, on June 14, 2018: photo by AFP

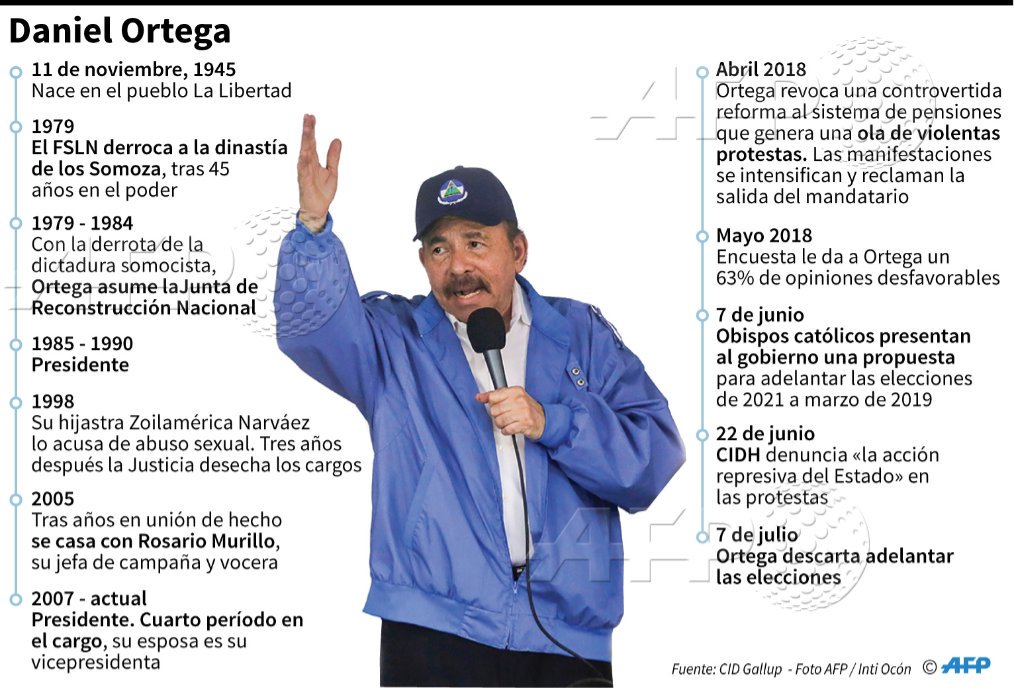

#Nicaragua Ficha del presidente nicaragüense, Daniel Ortega #AFP @AFPgraphics: image via Agence France-Presse @AFP, 17 July 2018

Untitled: photo by Tom Akaradech, 14 July 2018

Untitled: photo by Tom Akaradech, 14 July 2018

Untitled: photo by Tom Akaradech, 14 July 2018

No comments:

Post a Comment