Donnybrook, Dublin: photo by Fergus O'Connor, c. 1920 (Fergus O'Connor Collection, National Library of Ireland)

Donnybrook, Dublin: photo by Fergus O'Connor, c. 1920 (Fergus O'Connor Collection, National Library of Ireland)

The most successful evocative experiment can only project

the echo of a past sensation, because, being an act of intellection, it

is conditioned by the prejudices of the intelligence which abstracts

from any given sensation, as being illogical and insignificant, a

discordant and frivolous intruder, whatever word or gesture, sound or

perfume, cannot be fitted into the puzzle of a concept. But the essence

of any new experience is contained precisely in this mysterious element

that the vigilant will reject as an anachronism. It is the axis about

which the sensation pivots, the centre of gravity of its coherence. So

that no amount of voluntary manipulation can reconstitute in its

integrity an impression that the will has -- so to speak -- buckled into

incoherence. But if, by accident, and given favourable

circumstances (a relaxation of the subject’s habit of thought and a

reduction of the radius of his memory, a generally diminished tension of

consciousness following upon a phase of extreme discouragement), if by

some miracle of analogy the central impression of a past sensation

recurs as an immediate stimulus which can be instinctively identified by

the subject with the model of duplication (whose integral purity has been retained because it has been forgotten),

then the total past sensation, not its echo nor its copy, but the

sensation itself, annihilating every spatial and temporal restriction,

comes in a rush to engulf the subject in all the beauty of its

infallible proportion.

Horse trams at corner of Bachelor's Walk and O'Connell Bridge [Dublin]: photo by Robert French, c. 1897 (Lawrence Photographic Collection, National Library of Ireland)

The most trivial experience -- he says in effect -- is encrusted with elements that logically are not related to it and have consequently been rejected by our intelligence: it is imprisoned in a vase filled with a certain perfume and a certain colour and raised to a certain temperature. These vases are suspended along the height of our years, and, not being accessible to our intelligent memory, are in a sense immune, the purity of their climatic content is guaranteed by forgetfulness, each one is kept at its distance, at its date. So that when the imprisoned microcosm is besieged in the manner described, we are flooded by a new air and a new perfume (new precisely because already experienced), and we breathe the true air of Paradise, of the only Paradise that is not the dream of a madman, the Paradise that has been lost.

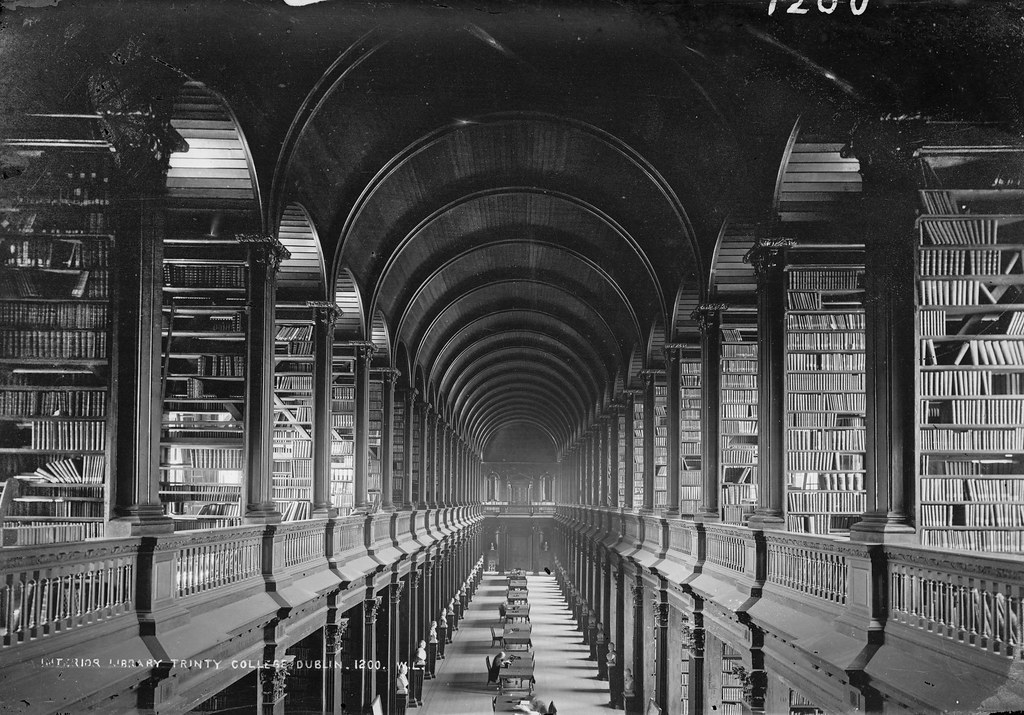

Long Room Library, Trinity College, Dublin: photo by Robert French, c. 1885 (Lawrence Photographic Collection, National Library of Ireland)

But if this mystical experience communicates an extratemporal essence, it follows that the communicant is for the moment an extratemporal being. Consequently the Proustian solution consists, in so far as it has been examined, in the negation of Time and Death, the negation of Death because the negation of Time. Death is dead because Time is dead. (At this point a brief impertinence, which consists in considering Le Temps Retrouvé almost as inappropriate a description of the Proustian solution as Crime and Punishment of a masterpiece that contains no allusion to either crime or punishment. Time is not recovered, it is obliterated. Time is recovered, and Death with it, when he leaves the library and joins the guests, perched in precarious decrepitude on the aspiring stilts of the former and preserved from the latter by a miracle of terrified equilibrium. If the title is a good title the scene in the library is an anticlimax.)

Samuel Beckett (b. Dublin 1906-d. Paris 1989): on involuntary memory: from Proust (1931)

Dublin street scene: photographer unknown, c. 1912 (Eason Collection. National Library of Ireland)

Dublin street scene: photographer unknown, c. 1912 (Eason Collection. National Library of Ireland)

Samuel Beckett. Pictured leaving the Royal Court Theatre, Sloane Square, London, via the stage door, after rehearsals of Happy Days starring Billie Whitelaw, as part of the Beckett season to celebrate his 70th birthday. April 1976: photo by Jane Bown (1925-2014) for The Observer via The Guardian, 17 October 2009

Samuel Beckett. Pictured leaving the Royal Court Theatre, Sloane Square, London, via the stage door, after rehearsals of Happy Days starring Billie Whitelaw, as part of the Beckett season to celebrate his 70th birthday. April 1976: photo by Jane Bown (1925-2014) for The Observer via The Guardian, 17 October 2009

Tuol Sleng genocide museum, Cambodia: photo by Ambroise Tézenas via the Guardian, 13 November 2014

Tuol Sleng genocide museum, Cambodia: photo by Ambroise Tézenas via the Guardian, 13 November 2014

Bottles and vases: Pietro Bigaglia, c. 1845, glassware (Museo del Vetro, Murano)

Bottles and vases: Pietro Bigaglia, c. 1845, glassware (Museo del Vetro, Murano)

2 comments:

Those photos have an evocative beauty that seems absent in most contemporary photography. But Beckett on Proust: thanks for fishing that out and giving it to us. Time & Death---the issues don't get any more fundamental. I think the solution is to never leave the library. [You may know that Bob Hershon's wife is Donna Brook, a fact I've always loved.]

Terry,

Oh, absolutely. Those archival photos the librarians have enhanced with highfalutin new scanning techniques (and as yet these are a relatively small fraction of the total holdings, the selections having been made with discrimination) offer entry to hidden worlds, the surface details evidencing a degree of care in living that would make it hard to dismiss or patronize the past as benighted.

The Dublin photos I've chosen capture scenes Beckett may have observed. The Trinity College Long Room Library, for certain. The other scenes shown here, varying degrees of probability, from highly likely to at least possible. No photos of the Foxrock neighbourhood where Sam grew up, and of course Foxrock was not Donnybrook.

"A brawl or fracas; a scene of chaos. Named from Donnybrook Fair, a notoriously disorderly event, held annually from 1204 until the middle of the 19th century. The town of Donnybrook comes from the Irish "Domhnach Broc", meaning 'The Church of Saint Broc'."

Post a Comment