Stunning Reuters image of the red glow of the Canada wild fire underneath the northern lights #FortMcMurray: image via Julia Macfarlane Verified account @juliamacfarlane, 7 May 2016 Alberta, Canada

The worshippers of Dionysus invoke their god (after Euripides: The Bacchae)

BACCHANTES [like a wail]. Bromius, Bromius . . .

BACCHANTES [like a wail]. Bromius, Bromius . . .

LEADER [progressively radiant]. He . . . is . . .

Sweet upon the mountains, such sweetness

As afterbirth, such sweetness as death.

His hand strap wildness, and breed it gentle

He infuses tameness with savagery.

I have seen him on the mountains, in vibrant fawn-skin

I have seen him smile in the red flash of blood

I have seen the raw heart of a mountain-lion

Yet pulsing in his throat.

In the mountains of Eritrea, in the deserts of Libya

In Phrygia whose copper hills ring with the cries of

Bromius, Zagreus, Dionysos,

I know he is the awaited, the covenant, promise,

Restorer of fullness to Nature's lean hours.

As milk he flows in the earth, as wine

In the hills. He runs in the nectar of bees, and

In the duct of their sting lurks -- Bromius.

Oh let his flames burn in you, gently,

Or else -- consume you it must -- consume you . . .

CHORUS. Bromius . . . Bromius . . .

LEADER. His hair a brush of foxfires in the wind

A streak of lightning, his thyrsus.

He runs, he dances,

Kindling the tepid

Spurring the stragglers

And the women are like banks to his river --

A stream of gold from beyond the desert --

They cradle the path of his will.

CHORUS. Come, come Dionysos . . .

[The worshippers of Dionysus invoke their god]: after Euripides: The Bacchae, 119-153: from Wole Soyinka (1934-): The Bacchae of Euripides, 1973

Yet pulsing in his throat.

In the mountains of Eritrea, in the deserts of Libya

In Phrygia whose copper hills ring with the cries of

Bromius, Zagreus, Dionysos,

I know he is the awaited, the covenant, promise,

Restorer of fullness to Nature's lean hours.

As milk he flows in the earth, as wine

In the hills. He runs in the nectar of bees, and

In the duct of their sting lurks -- Bromius.

Oh let his flames burn in you, gently,

Or else -- consume you it must -- consume you . . .

CHORUS. Bromius . . . Bromius . . .

LEADER. His hair a brush of foxfires in the wind

A streak of lightning, his thyrsus.

He runs, he dances,

Kindling the tepid

Spurring the stragglers

And the women are like banks to his river --

A stream of gold from beyond the desert --

They cradle the path of his will.

CHORUS. Come, come Dionysos . . .

[The worshippers of Dionysus invoke their god]: after Euripides: The Bacchae, 119-153: from Wole Soyinka (1934-): The Bacchae of Euripides, 1973

This photo taken in #FortMcMurray renders me utterly speechless. People, homes, businesses, trees, wildlife, gone ...: image via Wendy M @quillfeather, 7 May 2016

The inexorable law of tragedy

derives the conflagration from a loose gas cap

but why should a forest harbour

a secret tragic wish to die of humanity

a secret tragic wish to die of humanity

Those who could still believe in a God

keeping up their courage

with a fable of the changeless

and the permanent

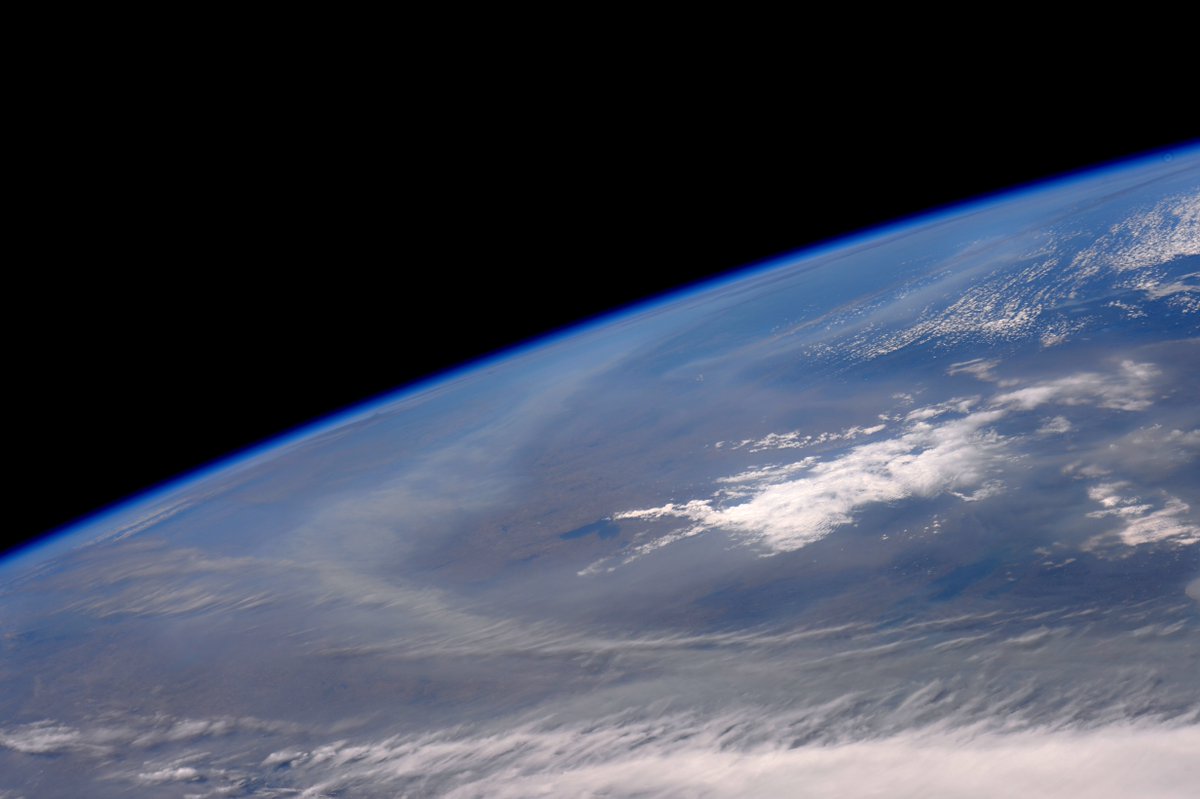

Smoke covering a vast area in @Canada. Our hearts go out to all those affected by the fires there. @SpaceStation: image via Tim Kopra @astro_tim, 8 May 2016 Houston, TX

Smoke

from the fires in Alberta, primarily the 210,000-acre blaze near Fort

McMurray, is affecting Saskatchewan, Manitoba, the north-central United

States, and many areas in the eastern U.S. The map above was generated

at 19:45 p.m. MDT May 7, 2016. Added yellow circle to emphasize a location on map, small red dots are fires burning.: image via NOAA Hazard Mapping System Fire and Smoke Product, 7 May 2016

On May 4, 2016, the the Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) on the Landsat 7 satellite acquired this false-color image of the wildfire that burned through Fort McMurray in Alberta, Canada. The image combines shortwave infrared, near infrared, and green light (bands 5-4-2). Near- and short-wave infrared help penetrate clouds and smoke to reveal the hot spots associated with active fires, which appear red. Smoke appears white and burned areas appear brown.: NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey, 4 May 2016

Dorian McCready, who was dropping off supplies to a command post, searched for a friend’s home in an evacuated neighborhood of Fort McMurray on Saturday to try to rescue some sentimental items for the friend: photo by Ian Willms for The New York Times, 8 May 2016

Evacuees from the wildfire taking refuge at the Bold Center in Lac La Biche, Alberta, 137 miles south of Fort McMurray, on Saturday: photo by Tyler Hicks/The New York Times, 8 May 2016

The inexorable law of tragedy

Payback is a Maserati parked in your perfectly clean driveway back at base camp

reduced to karmic ash

while you chill with your phone in a sleeping bag

one among many isolated points of light

in the big gym at Lac La Biche

one among many isolated points of light

in the big gym at Lac La Biche

far from empty but as yet still untoasted downtown Fort Make Money

A displaced person looks at the fire on a mobile phone at a makeshift evacuee center in Lac la Biche, Alberta: photo by Cole Burston / AFP, 5 May 2016

A displaced person looks at the fire on a mobile phone at a makeshift evacuee center in Lac la Biche, Alberta: photo by Cole Burston / AFP, 5 May 2016

A convoy of evacuees headed south from Fort McMurray on Saturday: photo by Ian Willms for The New York Times, 8 May 2016

A

vehicle is stored in a shipping container at Ferrari Maserati of

Alberta, in Calgary, to protect it from hail storms. Low oil prices have

negatively impacted Alberta’s economy.: photo by Ian Willms for The New York Times, 12 October 2015

The

waterpark at MacDonald Island Park in Fort McMurray. The increase in

oil sands development has turned obscure Fort McMurray into a boomtown

and an outsize contributor to the entire Canadian economy.: photo by Ian Willms for The New York Times, 12 October 2015

A bus stop in Fort McMurray from which workers are taken to oil sands sites: photo by Ian Willms for The New York Times, 12 October 2015

A bus chartered to take workers to and from oil sands sites sits in the new Parson’s Creek subdivision: photo by Ian Willms for The New York Times, 12 October 2015

New houses in the Parson’s Creek subdivision attract oil sands workers who are looking to establish themselves in Fort McMurray: photo by Ian Willms for The New York Times, 12 October 2015

one among many isolated points of light

The Syncrude oil sands plant, north of Fort McMurray, Alberta, Canada. Alberta is home to the third-largest crude oil deposits in the world: photo by Ian Willms for The New York Times, 12 October 2015

The Syncrude oil sands plant, north of Fort McMurray, Alberta, Canada. Alberta is home to the third-largest crude oil deposits in the world: photo by Ian Willms for The New York Times, 12 October 2015

A tailings pond near Fort McMurray, Alberta, Canada: photo by Ian Willms for The New York Times, 12 October 2015

A

A A tailings pond near Fort McMurray, Alberta, Canada: photo by Ian Willms for The New York Times, 12 October 2015

A

scarecrow set up in a tailings pond, north of Fort McMurray. Many

energy companies have too much invested in the oil sands to slow down or

turn off the taps.: photo by Ian Willms for The New York Times, 12 October 2015

He . . . is . . .

Sweet upon the mountains, such sweetness

As afterbirth, such sweetness as death

Flames erupt as the convoy of #FortMacFire finally make their way through the city they fled days ago: image via Avery Haines @CityAvery, 7 March 2016

A massive wildfire, which caused a mandatory evacuation, rages south of Fort McMurray near Anzac, Alberta, Canada: photo by Chris Schwarz / Government of Alberta / Reuters, 4 May 2016

A plume of smoke hangs in the air as forest fires rage on in the distance in Fort McMurray. Numerous vehicles can be seen abandoned on the highways leading from the raging forest fires in Fort McMurray and neighbouring communities have banded together to offer support in the form of food, water, and gasoline.: photo by Cole Burston / AFP, 4 May 2016

Smoke billows from the Fort McMurray wildfires as a

truck drives down the highway in Kinosis, Alberta: photo by Mark Blinch / Reuters, 5 May 2016

Officers look on as smoke from Fort McMurray's raging wildfires billows into the air after their city was evacuated: photo by Topher Seguin / Reuters, 4 May 2016

A toy car remains among the ruins of destroyed buildings

after wildfires tore through the Waterways area of Fort McMurray: photo by Brad Readman / Alberta Fire Fighters Association / Reuters, 5 May 2016

A flock of birds flies in formation as smoke billows from

the Fort McMurray wildfires above Kinosis, Alberta: photo by Mark Blinch / Reuters, 5 May 2016

Smoke and flames can be seen along the highway near Fort McMurray, Alberta. Canadian police led convoys of cars through the burning ghost town of Fort McMurray Friday in a risky operation to get people to safety far to the south. In the latest chapter of the drama triggered by monster fires in Alberta's oil sands region, the 50-car convoys are driving through the city at about 50-60 kilometers per hour (30-40 mph), TV footage showed.: photo by Cole Burston / AFP, 6 May 2016

A blazing housing estate in Huskvarna, Sweden: photo by Anna Hallams / TT News Agency / Reuters, 1 May 2016

Police officers detain a protester during anti-capitalist protests following May Day marches in Seattle, Washington: photo by David Ryder / Reuters, 1 May 2016

Dilek Dundar, Can Dundar's wife, and his lawyer, 2nd left, overpower a gunman just after an attack on Can Dundar outside the city's main courthouse in Istanbul on May 6, 2016. A man shouted “traitor” and fired two shots at the prominent Turkish journalist outside a courthouse where he is on trial, accused of revealing state secrets for his reports on alleged government arms-smuggling to Syria. Can Dundar, editor-in-chief of the opposition Cumhuriyet newspaper, escaped the attack unhurt, but Yavuz Senkal, a journalist working for private NTV television was slightly injured in one of his legs.: photo by Can Erok / AP, 6 May 2016

A Nepalese Hindu devotee takes a holy bath as they mark the Mother’s Day Festival at Matathirtha on the outskirts of Kathmandu: photo by Prakash Methema/AFP, 6 May 2016

A Nepalese Hindu devotee takes a holy bath as they mark the Mother’s Day Festival at Matathirtha on the outskirts of Kathmandu: photo by Prakash Methema/AFP, 6 May 2016

North Korean men and women carry bouquets of decorative flowers as they wait at the Kim Il Sung Square: photo by Wong Maye-E/AP, 6 May 2016

North Korean men and women carry bouquets of decorative flowers as they wait at the Kim Il Sung Square: photo by Wong Maye-E/AP, 6 May 2016

A horse gets a bath after a morning workout at Churchill Downs in Louisville, Kentucky. The 142nd running of the Kentucky Derby is scheduled for Saturday.: photo by Charlie Riedel/AP, 6 May 2016

A horse gets a bath after a morning workout at Churchill Downs in Louisville, Kentucky. The 142nd running of the Kentucky Derby is scheduled for Saturday.: photo by Charlie Riedel/AP, 6 May 2016

Tar Sands Healing Walk. Syncrude is one of many companies doing work up at the tar sands. The two bison in the photo were the only two I saw during my time in the region.: photo by taylorandayumi, 2 July 2013

Tar Sands Healing Walk. On the drive up to Fort McMurray from Edmonton, we went through a ferocious thunderstorm with heavy rain, wind and lightning. The lightning crashes were beautiful, as was this rainbow.: photo by taylorandayumi, 2 July 2013

Tar Sands Healing Walk. The thunderstorm eventually drifted off, leaving a gorgeous sunset. Because we were so far off, the sunset lasted for hours. It never got completely dark before the sun rose several hours later.: photo by taylorandayumi, 2 July 2013

The 2014 Tar Sands Healing Walk: photo by Rainforest Action Network, 28 June 2014

Map showing the extent of the oil sands in Alberta, Canada. The three oil sand deposits are known as the Athabasca Oil Sands, the Cold Lake Oil Sands, and the Peace River Oil Sands: image by Norman Einstein, 10 May 2006

Athabasca oil sands mining field: NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, acquired 29 July 2009 using EO-1 Advanced Land Rover data courtesy of the NASA EO-I team; caption by Holli Riebeek (NASA)

The mines follow the course of the Athabasca River, the dark brown ribbon of water that runs down the center of the image. The river is essential to the operation. Over the course of its very long lifetime, the river has eroded through the sediment that once covered the oil deposit, gradually bringing it close to the surface. Without the river, the oil sands would likely be buried beneath a thick layer of earth.

Nitrogen emissions from Athabasca oil sands mining operations, data acquired 2005 - 2010

Athabasca Oil Sands mining operations, Nitrogen emissions, data acquired 2005-2010: graphics by NASA Earth Observatory

Smoke and flames can be seen along the highway near Fort McMurray, Alberta. Canadian police led convoys of cars through the burning ghost town of Fort McMurray Friday in a risky operation to get people to safety far to the south. In the latest chapter of the drama triggered by monster fires in Alberta's oil sands region, the 50-car convoys are driving through the city at about 50-60 kilometers per hour (30-40 mph), TV footage showed.: photo by Cole Burston / AFP, 6 May 2016

Smoke rises in a burned-out neighborhood in Fort

McMurray, Alberta, after wildfires forced the

mass evacuations of the areas around Fort McMurray: photo by Bonnyville Regional Fire Authority / Reuters, 6 May 2016

A blazing housing estate in Huskvarna, Sweden: photo by Anna Hallams / TT News Agency / Reuters, 1 May 2016

Firefighters battle a three-alarm fire in the historic

Serbian Orthodox Cathedral of St. Sava in New York.

Authorities say no injuries were reported in the blaze that broke out

early Sunday evening in the church.: photo by Kathy Willens / AP, 1 May 2016

St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Adam Wainwright is splashed

with water after hitting a three-run home run during the fourth inning

of a baseball game against the Philadelphia Phillies, in

St. Louis: photo by Billy Hurst / AP, 2 May 2016

Police officers detain a protester during anti-capitalist protests following May Day marches in Seattle, Washington: photo by David Ryder / Reuters, 1 May 2016

Dilek Dundar, Can Dundar's wife, and his lawyer, 2nd left, overpower a gunman just after an attack on Can Dundar outside the city's main courthouse in Istanbul on May 6, 2016. A man shouted “traitor” and fired two shots at the prominent Turkish journalist outside a courthouse where he is on trial, accused of revealing state secrets for his reports on alleged government arms-smuggling to Syria. Can Dundar, editor-in-chief of the opposition Cumhuriyet newspaper, escaped the attack unhurt, but Yavuz Senkal, a journalist working for private NTV television was slightly injured in one of his legs.: photo by Can Erok / AP, 6 May 2016

Villarrica Volcano is seen at night from Villarrica National Park in Pucon, Chile: photo by Cristobal Saavedra / Reuters, 4 May 2016

A Nepalese Hindu devotee takes a holy bath as they mark the Mother’s Day Festival at Matathirtha on the outskirts of Kathmandu: photo by Prakash Methema/AFP, 6 May 2016

A Nepalese Hindu devotee takes a holy bath as they mark the Mother’s Day Festival at Matathirtha on the outskirts of Kathmandu: photo by Prakash Methema/AFP, 6 May 2016

North Korean men and women carry bouquets of decorative flowers as they wait at the Kim Il Sung Square: photo by Wong Maye-E/AP, 6 May 2016

North Korean men and women carry bouquets of decorative flowers as they wait at the Kim Il Sung Square: photo by Wong Maye-E/AP, 6 May 2016

A horse gets a bath after a morning workout at Churchill Downs in Louisville, Kentucky. The 142nd running of the Kentucky Derby is scheduled for Saturday.: photo by Charlie Riedel/AP, 6 May 2016

A horse gets a bath after a morning workout at Churchill Downs in Louisville, Kentucky. The 142nd running of the Kentucky Derby is scheduled for Saturday.: photo by Charlie Riedel/AP, 6 May 2016

I know he is the awaited, the covenant, promise,

Restorer of fullness to Nature's lean hours.

Tar Sands Healing Walk. Syncrude is one of many companies doing work up at the tar sands. The two bison in the photo were the only two I saw during my time in the region.: photo by taylorandayumi, 2 July 2013

Tar Sands Healing Walk. On the drive up to Fort McMurray from Edmonton, we went through a ferocious thunderstorm with heavy rain, wind and lightning. The lightning crashes were beautiful, as was this rainbow.: photo by taylorandayumi, 2 July 2013

Tar Sands Healing Walk. The thunderstorm eventually drifted off, leaving a gorgeous sunset. Because we were so far off, the sunset lasted for hours. It never got completely dark before the sun rose several hours later.: photo by taylorandayumi, 2 July 2013

The 2014 Tar Sands Healing Walk: photo by Rainforest Action Network, 28 June 2014

As milk he flows in the earth, as wine

In the hills. He runs in the nectar of bees, and

In the duct of their sting lurks -- Bromius.

Oh let his flames burn in you, gently,

Or else -- consume you it must -- consume you . . .

#TarSands Reporting Project film to premier at Media Democracy Days Friday 7pm: image via Vancouver Observer @VanObserver, 7 November 2014

More than 100 birds die after landing on #tarsands waste ponds in Canada: image via Shawna @S_WhiteBear, 7 November 2014

Picture of #Tarsands tailing ponds created by

removal of Boreal forest - compared to Mordor by @londonmining #olsx:

image via Occupy London @OccupyLondon, 8 November 2014

Reports of birds landing in toxic #tarsands tailing lakes spark investigation: image via Mike Hudema @MikeHudema, 5 November 2014

Nearly 100 birds land in three #oilsands tailings ponds: image via Everett Coldwell @EverettColdwell, 5 November 2014

Photographer @ianwillms documents a typical day in Alberta's Fort McMurray: image via AACC @artsandclimate, 11 November 2014

I know he is the awaited, the covenant, promise

How should this play any role in one of the world's largest aquifers? #TarSands #DirtyOil #WaterIsLife #NoKXL: image via tara zhaabowekwe @zhaabowekwe, 17 November 2014

Map showing the extent of the oil sands in Alberta, Canada. The three oil sand deposits are known as the Athabasca Oil Sands, the Cold Lake Oil Sands, and the Peace River Oil Sands: image by Norman Einstein, 10 May 2006

Athabasca oil sands mining field: NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, acquired 29 July 2009 using EO-1 Advanced Land Rover data courtesy of the NASA EO-I team; caption by Holli Riebeek (NASA)

In the ranking of the world’s proven

oil reserves, Canada stands behind only Saudi Arabia. Canada possesses

an estimated 178.6 billion barrels of crude oil accessible using current

technology. Of this reserve, 174 billion barrels are in Alberta’s oil

sand fields, which cover 140,200 square kilometers (54,132 square miles)

of the province. The largest oil sand field is Athabasca, shown here.

Oil sands consist of sand coated in water and a sticky film of

bitumen, a heavy oil. The bitumen can be rinsed from the sand and

refined into fuels. In some cases, the bitumen-encased sand can be

pumped from wells like standard oil, but in Athabasca, the sands are at

or near the surface. Here, oil companies scoop the sand from the surface

after stripping off overlying vegetation and top soil. The result is

illustrated in this true-color image. Earthy open-pit mines and muddy

tailing ponds replaced the dark green boreal forest.

The mines follow the course of the Athabasca River, the dark brown ribbon of water that runs down the center of the image. The river is essential to the operation. Over the course of its very long lifetime, the river has eroded through the sediment that once covered the oil deposit, gradually bringing it close to the surface. Without the river, the oil sands would likely be buried beneath a thick layer of earth.

The river is also key to the mining process. To separate the bitumen

from the sand, refineries bathe the sands in hot water. The contaminated

water cannot be returned to the Athabasca River, from which it was

drawn, and it ends up in tailing ponds, visible in the image. The

tailing ponds are one of the environmental risks of these mines. The

ponds replace natural wetlands and because they contain toxic chemicals,

they are a threat to wildlife. In April 2008, hundreds of migrating

ducks died after landing on a tailing pond, said news reports. Local

residents worry that the toxic water may be leaking into the ground

water or the Athabasca River, which, as the image illustrates, is very

near many of the ponds.

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 23 July 1984 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 28 September 1985 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 14 August 1986 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 18 September 1987 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 4 September 1988 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 6 August 1989 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 24 July 1990 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 27 July 1991 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 13 July 1992 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 17 August 1993 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 26 July 1994 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 24 September 1995 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 22 June 1996 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 12 August 1997 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 5 July 1998 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 15 June 1999 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 13 September 2000 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 7 August 2001 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 11 September 2002 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 30 September 2003 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 28 June 2004 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 5 October 2005 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 21 August 2006 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 30 July 2007 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 25 July 2008 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 14 September 2009 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 3 October 2010 (NASA)

Athabasca Oil Sands: satellite image by NASA Earth Observatory, 15 May 2011 (NASA)

Buried under Canada’s boreal forest is one of the world’s largest

reserves of oil. Bitumen—a very thick and heavy form of oil (also

called asphalt) -- coats grains of sand and other minerals in a deposit

that covers about 142,200 square kilometers (54,900 square miles) of

northwest Alberta. According to a 2003 estimate, Alberta has the

capacity to produce 174.5 billion barrels of oil. Only 20 percent of the oil sands lie near the surface where they

can easily be mined, and these deposits flank the Athabasca River. The

rest of the oil sands are buried more than 75 meters below ground and

are extracted by injecting hot water into a well that liquefies the oil

for pumping. In 2010, surface mines produced 356.99 million barrels of

crude oil, while in situ production (the hot water wells) yielded 189.41 million barrels of oil.

This series of images from the Landsat satellite shows the growth of surface mines over the Athabasca oil sands between 1984 and 2011. The Athabasca River runs through the center of the scene, separating two major operations. To extract the oil at these locations, oil producers remove the sand in big, open-pit mines, which are tan and irregularly shaped. The sand is rinsed with hot water to separate the oil, and then the sand and wastewater are stored in "tailings ponds,” which have smooth tan or green surfaces in satellite images.

The process of extracting oil from the sand is expensive. It takes two tons of sand to produce one barrel of crude oil. Great Canadian Oil Sands opened the first large-scale mine in 1967, but growth was slow until 2000 because the global cost of a barrel of oil was too low to make oil sands profitable.

The images above show slow growth between 1984 and 2000, followed by a decade of more rapid development. The first mine (from 1967, now part of the Millennium Mine) is visible near the Athabasca River in the 1984 image. The only new development visible between 1984 and 2000 is the Mildred Lake Mine (west of the river), which began production in 1996.

After 2000, the price of oil began to climb, and investment in oil sands became profitable. The Millennium Mine expanded east of the Athabasca River, and the Steepbank Mine was developed in the east. The Mildred Lake Mine also shows evidence of growth. It is a trend that is likely to continue since permits have been approved to expand mines in this region. The large images include a view of additional mines developing to the north.

Oil sand mining has a large impact on the environment. Forests must be cleared for both open-pit and in situ mining. Pit mines can grow to more than 80 meters depth, as massive trucks remove up to 720,000 tons of sand every day. As of September 2011, roughly 663 square kilometers (256 square miles) of land had been disturbed for oil sand mining. Companies are required to restore the land after they have finished mining. In this series of images, the large tailings pond from the 1967 mine was gradually drained and filled in. Though the mining companies planted grasses on the site, the images don’t show plant growth as of 2011.

Tailings ponds contain a number of toxins that can leak into the groundwater or the Athabasca River. The mining and extraction process releases sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, hydrocarbons, and fine particulate matter into the atmosphere.

Because it takes energy to mine and separate oil from the sands, oil sands extraction releases more greenhouse gases than other forms of oil production. The mines shown in the image emitted more than 20 million tons of greenhouse gases in 2008— a product of both oil production and electricity production for the mining operation. The effort produced the equivalent of 86 to 103 kilograms of carbon dioxide for every barrel of crude oil produced. By comparison, 27 to 58 kilograms of carbon dioxide are emitted in the conventional production of a barrel of crude oil.

Canada, a country with strict environmental laws, is the leading source of oil for the United States, the world’s largest consumer of oil. The oil sands contain enough oil to produce 2.5 million barrels of oil per day for 186 years. The United States consumes 18.8 million barrels of oil per day. TransCanada has proposed building a pipeline to bring oil from the Athabasca oil sands directly to refineries in the United States.

This series of images from the Landsat satellite shows the growth of surface mines over the Athabasca oil sands between 1984 and 2011. The Athabasca River runs through the center of the scene, separating two major operations. To extract the oil at these locations, oil producers remove the sand in big, open-pit mines, which are tan and irregularly shaped. The sand is rinsed with hot water to separate the oil, and then the sand and wastewater are stored in "tailings ponds,” which have smooth tan or green surfaces in satellite images.

The process of extracting oil from the sand is expensive. It takes two tons of sand to produce one barrel of crude oil. Great Canadian Oil Sands opened the first large-scale mine in 1967, but growth was slow until 2000 because the global cost of a barrel of oil was too low to make oil sands profitable.

The images above show slow growth between 1984 and 2000, followed by a decade of more rapid development. The first mine (from 1967, now part of the Millennium Mine) is visible near the Athabasca River in the 1984 image. The only new development visible between 1984 and 2000 is the Mildred Lake Mine (west of the river), which began production in 1996.

After 2000, the price of oil began to climb, and investment in oil sands became profitable. The Millennium Mine expanded east of the Athabasca River, and the Steepbank Mine was developed in the east. The Mildred Lake Mine also shows evidence of growth. It is a trend that is likely to continue since permits have been approved to expand mines in this region. The large images include a view of additional mines developing to the north.

Oil sand mining has a large impact on the environment. Forests must be cleared for both open-pit and in situ mining. Pit mines can grow to more than 80 meters depth, as massive trucks remove up to 720,000 tons of sand every day. As of September 2011, roughly 663 square kilometers (256 square miles) of land had been disturbed for oil sand mining. Companies are required to restore the land after they have finished mining. In this series of images, the large tailings pond from the 1967 mine was gradually drained and filled in. Though the mining companies planted grasses on the site, the images don’t show plant growth as of 2011.

Tailings ponds contain a number of toxins that can leak into the groundwater or the Athabasca River. The mining and extraction process releases sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, hydrocarbons, and fine particulate matter into the atmosphere.

Because it takes energy to mine and separate oil from the sands, oil sands extraction releases more greenhouse gases than other forms of oil production. The mines shown in the image emitted more than 20 million tons of greenhouse gases in 2008— a product of both oil production and electricity production for the mining operation. The effort produced the equivalent of 86 to 103 kilograms of carbon dioxide for every barrel of crude oil produced. By comparison, 27 to 58 kilograms of carbon dioxide are emitted in the conventional production of a barrel of crude oil.

Canada, a country with strict environmental laws, is the leading source of oil for the United States, the world’s largest consumer of oil. The oil sands contain enough oil to produce 2.5 million barrels of oil per day for 186 years. The United States consumes 18.8 million barrels of oil per day. TransCanada has proposed building a pipeline to bring oil from the Athabasca oil sands directly to refineries in the United States.

Nitrogen emissions from Athabasca oil sands mining operations, data acquired 2005 - 2010

Athabasca Oil Sands mining operations, Nitrogen emissions, data acquired 2005-2010: graphics by NASA Earth Observatory

Using data from a

NASA satellite, researchers have found that the emission of pollutants

from oil sands mining operations in Canada’s Alberta Province are

comparable to the emissions from a

large power plant or a moderately sized city. The emissions from the

energy-intensive mining effort come from excavators, dump trucks,

extraction pumps and wells, and refining facilities where the oil sands

are processed.

Oil sands (also known as tar sands) are actually bitumen, a very thick and heavy form of oil that coats grains of sand and other minerals. Once extracted, that asphalt-like oil is partially refined so that it can be transported through pipelines to other refining facilities.

The top two maps above depict the concentration of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) in the air above the main oil sands mining operation along the Athabasca River, as observed from 2005 to 2007 (left) and 2008 to 2010 (right). The lower map shows those emissions in the broader context of the western provinces of Canada and the northern United States from 2005 to 2010. All data were acquired by the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) on NASA’s Aura satellite.

The oil sands deposit in northwest Alberta covers about 142,200 square kilometers (54,900 square miles). Only 20 percent of the oil sands lie near the surface where they can easily be mined, while the rest of the oil sands are buried more than 75 meters below ground and are extracted by injecting hot water into a well that liquefies the oil for pumping. About 1.8 million barrels of oil were produced daily in 2010 from the Canadian oil sands.

NASA Earth Observatory images created by Jesse Allen, using OMI data provided courtesy of Chris McLinden, Environment Canada and Ronald van der A, KMNI. Mining permit footprints provided courtesy of Matt Hanneman, Global Forest Watch Canada. Caption by Michael Carlowicz, based on reporting from the American Geophysical Union.

Dust hangs in the sunset sky above the Suncor Millennium mine, an open-pit north of Fort McMurray, Alberta: photo by Peter Essick, in The Canadian Oil Boom: Scraping Bottom, National Geographic, March 2009

Nor is Syncrude alone. Within a 20-mile radius are a total of six mines that produce nearly three-quarters of a million barrels of synthetic crude oil a day; and more are in the pipeline. Wherever the bitumen layer lies too deep to be strip-mined, the industry melts it "in situ" with copious amounts of steam, so that it can be pumped to the surface. The industry has spent more than $50 billion on construction during the past decade, including some $20 billion in 2008 alone. Before the collapse in oil prices last fall, it was forecasting another $100 billion over the next few years and a doubling of production by 2015, with most of that oil flowing through new pipelines to the U.S. The economic crisis has put many expansion projects on hold, but it has not diminished the long-term prospects for the oil sands. In mid-November, the International Energy Agency released a report forecasting $120-a-barrel oil in 2030 -- a price that would more than justify the effort it takes to get oil from oil sands.

Nowhere on Earth is more earth being moved these days than in the Athabasca Valley. To extract each barrel of oil from a surface mine, the industry must first cut down the forest, then remove an average of two tons of peat and dirt that lie above the oil sands layer, then two tons of the sand itself. It must heat several barrels of water to strip the bitumen from the sand and upgrade it, and afterward it discharges contaminated water into tailings ponds like the one near Mildred Lake. They now cover around 50 square miles. Last April some 500 migrating ducks mistook one of those ponds, at a newer Syncrude mine north of Fort McKay, for a hospitable stopover, landed on its oily surface, and died. The incident stirred international attention -- Greenpeace broke into the Syncrude facility and hoisted a banner of a skull over the pipe discharging tailings, along with a sign that read "World's Dirtiest Oil: Stop the Tar Sands."

The U.S. imports more oil from Canada than from any other nation, about 19 percent of its total foreign supply, and around half of that now comes from the oil sands. Anything that reduces our dependence on Middle Eastern oil, many Americans would say, is a good thing. But clawing and cooking a barrel of crude from the oil sands emits as much as three times more carbon dioxide than letting one gush from the ground in Saudi Arabia. The oil sands are still a tiny part of the world's carbon problem -- they account for less than a tenth of one percent of global CO2 emissions -- but to many environmentalists they are the thin end of the wedge, the first step along a path that could lead to other, even dirtier sources of oil: producing it from oil shale or coal. "Oil sands represent a decision point for North America and the world," says Simon Dyer of the Pembina Institute, a moderate and widely respected Canadian environmental group. "Are we going to get serious about alternative energy, or are we going to go down the unconventional-oil track? The fact that we're willing to move four tons of earth for a single barrel really shows that the world is running out of easy oil."

Syncrude Canada's base mine, Mildred Lake, Alberta. The yellow structures are the bases of pyramids made of sulphur. It is not economically profitable for Syncrude to sell the sulphur, so it is stockpiled instead. Beyond the mining operation is the tailings pond, contained by what is recognized as the largest dam in the world. The extraction plant is just to the right in this photograph, and most of the mine is to the left: photo by TastyCakes, 4 April 2004; image by Jamitzky, 15 July 2006

It was only for a few minutes but the sight of rain has never been so good #ymmfire #FortMacFire: image via RMWB @RMWoodBuffalo 8 May 2016

I'd rather not live on a planet that looks like this. And you? #NoKXL Plz read up on the #TarSands and RT: image via Tinsel Korey @tinselkoey, 17 November 2014

Oil sands (also known as tar sands) are actually bitumen, a very thick and heavy form of oil that coats grains of sand and other minerals. Once extracted, that asphalt-like oil is partially refined so that it can be transported through pipelines to other refining facilities.

The top two maps above depict the concentration of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) in the air above the main oil sands mining operation along the Athabasca River, as observed from 2005 to 2007 (left) and 2008 to 2010 (right). The lower map shows those emissions in the broader context of the western provinces of Canada and the northern United States from 2005 to 2010. All data were acquired by the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) on NASA’s Aura satellite.

The oil sands deposit in northwest Alberta covers about 142,200 square kilometers (54,900 square miles). Only 20 percent of the oil sands lie near the surface where they can easily be mined, while the rest of the oil sands are buried more than 75 meters below ground and are extracted by injecting hot water into a well that liquefies the oil for pumping. About 1.8 million barrels of oil were produced daily in 2010 from the Canadian oil sands.

NASA Earth Observatory images created by Jesse Allen, using OMI data provided courtesy of Chris McLinden, Environment Canada and Ronald van der A, KMNI. Mining permit footprints provided courtesy of Matt Hanneman, Global Forest Watch Canada. Caption by Michael Carlowicz, based on reporting from the American Geophysical Union.

Dust hangs in the sunset sky above the Suncor Millennium mine, an open-pit north of Fort McMurray, Alberta: photo by Peter Essick, in The Canadian Oil Boom: Scraping Bottom, National Geographic, March 2009

The oil sands industry has utterly

transformed this part of northeastern Alberta in just the past few

years, with astonishing speed. Where trapline and cabin once were, and the forest, there is

now a large open-pit mine. Here Syncrude, Canada's largest oil producer,

digs bitumen-laced sand from the ground with electric shovels five

stories high, then washes the bitumen off the sand with hot water and

sometimes caustic soda. Next to the mine, flames flare from the stacks

of an "upgrader," which cracks the tarry bitumen and converts it into

Syncrude Sweet Blend, a synthetic crude that travels down a pipeline to

refineries in Edmonton, Alberta; Ontario, and the United States.

Mildred Lake, meanwhile, is now dwarfed by its neighbor, the Mildred

Lake Settling Basin, a four-square-mile lake of toxic mine tailings. The

sand dike that contains it is by volume one of the largest dams in the

world.

Nor is Syncrude alone. Within a 20-mile radius are a total of six mines that produce nearly three-quarters of a million barrels of synthetic crude oil a day; and more are in the pipeline. Wherever the bitumen layer lies too deep to be strip-mined, the industry melts it "in situ" with copious amounts of steam, so that it can be pumped to the surface. The industry has spent more than $50 billion on construction during the past decade, including some $20 billion in 2008 alone. Before the collapse in oil prices last fall, it was forecasting another $100 billion over the next few years and a doubling of production by 2015, with most of that oil flowing through new pipelines to the U.S. The economic crisis has put many expansion projects on hold, but it has not diminished the long-term prospects for the oil sands. In mid-November, the International Energy Agency released a report forecasting $120-a-barrel oil in 2030 -- a price that would more than justify the effort it takes to get oil from oil sands.

Nowhere on Earth is more earth being moved these days than in the Athabasca Valley. To extract each barrel of oil from a surface mine, the industry must first cut down the forest, then remove an average of two tons of peat and dirt that lie above the oil sands layer, then two tons of the sand itself. It must heat several barrels of water to strip the bitumen from the sand and upgrade it, and afterward it discharges contaminated water into tailings ponds like the one near Mildred Lake. They now cover around 50 square miles. Last April some 500 migrating ducks mistook one of those ponds, at a newer Syncrude mine north of Fort McKay, for a hospitable stopover, landed on its oily surface, and died. The incident stirred international attention -- Greenpeace broke into the Syncrude facility and hoisted a banner of a skull over the pipe discharging tailings, along with a sign that read "World's Dirtiest Oil: Stop the Tar Sands."

The U.S. imports more oil from Canada than from any other nation, about 19 percent of its total foreign supply, and around half of that now comes from the oil sands. Anything that reduces our dependence on Middle Eastern oil, many Americans would say, is a good thing. But clawing and cooking a barrel of crude from the oil sands emits as much as three times more carbon dioxide than letting one gush from the ground in Saudi Arabia. The oil sands are still a tiny part of the world's carbon problem -- they account for less than a tenth of one percent of global CO2 emissions -- but to many environmentalists they are the thin end of the wedge, the first step along a path that could lead to other, even dirtier sources of oil: producing it from oil shale or coal. "Oil sands represent a decision point for North America and the world," says Simon Dyer of the Pembina Institute, a moderate and widely respected Canadian environmental group. "Are we going to get serious about alternative energy, or are we going to go down the unconventional-oil track? The fact that we're willing to move four tons of earth for a single barrel really shows that the world is running out of easy oil."

Robert Kunzig, from The Canadian Oil Boom: Scraping Bottom, National Geographic, March 2009

Syncrude Canada's base mine, Mildred Lake, Alberta. The yellow structures are the bases of pyramids made of sulphur. It is not economically profitable for Syncrude to sell the sulphur, so it is stockpiled instead. Beyond the mining operation is the tailings pond, contained by what is recognized as the largest dam in the world. The extraction plant is just to the right in this photograph, and most of the mine is to the left: photo by TastyCakes, 4 April 2004; image by Jamitzky, 15 July 2006

It was only for a few minutes but the sight of rain has never been so good #ymmfire #FortMacFire: image via RMWB @RMWoodBuffalo 8 May 2016

I'd rather not live on a planet that looks like this. And you? #NoKXL Plz read up on the #TarSands and RT: image via Tinsel Korey @tinselkoey, 17 November 2014

5 comments:

"A stream of gold from beyond the desert"

Amazing photos Tom -- the fires, the smoke, that flock of birds ("in formation as smoke billows from the Fort McMurray wildfires"), that cancer growing in the green along the banks of the Athabasca River . . . shocking.

Steve,

It seems there is the sentiment among the Boomtown Nation Dark Money loyalists -- that is, Canadians in general, and in specific the public relations specialists of the naked-profiteering energy companies that have made Calgary the Houston of the Far North (I mean, Syncrude -- what's in a name!) -- that it's "insensitive" to mention that the entire endangered populace of the invented/imported "community" at the centre of in this human-created near-disaster owes its existence and subsistence to the rampant and unapologetic destruction of the earth.

The added fillip that the current world oil glut renders this added accumulation of the foulest stuff ever extracted redundant is a touch that helps us understand what's at stake. The current arrangement is suicidal yet continues to remain unchallenged. Accumulation does not impede extraction. The cultural work of making cheap gas available to the masses and advertising the virtues of mad use of it 24x7, that's ongoing, so that no matter how large the "reserves", the resource expenditure/exhaustion will always keep outdistancing the gleam in the eye of even the most optimistic of the corporate greedheads.

There is also apparently some "debate" over whether climate change may have played a part in the Alberta fires. Hmm. 91 degrees F on Mayday in the marge of the Arctic. No rain forever. What's so unusual about that.

What could have made that happen. Dunno. Let's jump in the car and pick up a couple of things at Safeway and wonder about it.

There's the East Bay Refinery Corridor tribal healing walk coming up soon, over this way... speaking of cancer growing along the shore.

Wole Soyinka came to Euripides with a post-colonialist sensibility trained in classic tragedy under Wilson Knight. I think he did a pretty good job on The Bacchae.

Thanks Tom, so well said and so true too -- no one talking about what "might be" the triangular connection between Tar Sands, climate change, Fort McMurray fire (how many acres burned at this point?), Dark Money indeed in the driver's seat . . .

That photo of deer in the river isn't Fort Mac.

Dear Saskboy,

Thanks for confirming a certain mild suspicion here.

Something about that picture brought back the visuals from last year's massive northern California wildfires. Further research now reveals that the person who posted it is an animal lover in New Zealand, which she calls Middle Earth. Perhaps from Middle Earth, everything out here that's on fire looks the same. Certainly every forest out here that's on fire, in these climate-changed days -- the period when anybody who hasn't already escaped to the unburnt bits of Middle Earth ought to be doing so ASAP -- bears a certain resemblance to every other forest that's on fire, when viewed from the POV of the endangered and absolutely innocent (they're the only innocent one) animals daring to call that forest home. You don't get a loose gas cap in a trailer camp much less gas or a trailer camp where there are no two-legged animals. And what are the two legged animals at Fort Make Money doing but Making Money. They are, I would concede, faithful devotees of their gods, the gods of Money. They don't exactly appear to be traditionalists, from here. Unless there is such a thing as a tradition of for-profit destruction and desolation-creation followed by predictable resource exhaustion, and moving on to the next filthy excavation site. But perhaps indeed there IS such a tradition, and this sort of environmental violation is now routine, and even accepted as an admirable contribution to the wonderful legend of The Human Family. Certainly I saw a lot of this in covering, as a grown-up boy reporter, stories like the 1978-1979 "Energy Boom" in Wyoming, the construction of the Trans Alaska pipeline, and so on. A loose collection of extremely able and acquisitive and accordingly very highly-paid mercenaries temporarily assembled in cheapjack housing in the middle of a wilderness, busily mucking up the only planet they or their miserable DNA will ever have a chance to inhabit. "Our" period in "history". The children of the future, if there are any, might be permitted to think of us as unreconstructed primitives sans excuse for the general incorrigible ignorance.

In any case, obviously there's been a bit of mild deception at work here, on the part of our dear picture-poster Wendy M @quillfeather. But I don't see any malice in it, and furthermore, from all the anecdotal reports out of Alberta, it's pretty plain that animals in the boreal forest suffered even more acutely from these fires than did the neo community of earthwrecker mercenary slaves at Fort Make Money.

Post a Comment